PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The bald eagle is an opportunistic, carnivorous forager native to North America. This large raptor prefers to reside near large bodies of water and is named for the iconic white coloring of its head contrasting with the dark plumage of its body. The bald eagle has been the national symbol of the U.S. since 1782 and was an endangered species until 1978.

Physiology

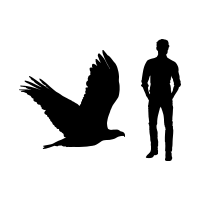

Adult bald eagles are extremely large birds with characteristically yellow eyes and bills, white heads and tails, and dark brown bodies, which may appear almost black. These birds have extremely large, powerful bodies and large heads, necks, bills, and feet with sharp talons. Generally, their plank-like wings have a span of 178 to 229 centimeters, their bodies are 79 to 94 centimeters long and they weigh about 4.3 kilograms. Their plumage alone weighs about 700 grams, which is twice as much as their skeleton.

With large, forward facing eyes, bald eagles likely have very good binocular vision. Although bald eagles do not have an adept sense of smell, they do avoid food items that taste spoiled.

Bald eagles have sexually monomorphic plumage coloration, although females generally have a somewhat larger body size.

The bald eagles undergoes four distinct maturation stages, each comprising one year of its life. Immediately after hatching, the bald eagle has dark eyes with pink legs and skin and flesh colored talons. The skin darkens to a bluish hue and the legs become yellow within the first 18 to 22 days of the bird’s life. Throughout the first year, the bodies, eyes, and beak are dark brown, although the underwing coverts and axillaries are white. In the bird’s second year, the eyes lighten, becoming grayish-brown, and they develop a light-colored superciliary line. The body becomes mottled white. During the bird’s third year, the bill and eyes begin to turn yellow and the coloration of the head feathers lighten. The body remains mottled. In the bird’s fourth year, the body becomes mostly dark and the head and tail become mostly white with some beige around the eyes and crown and isolated dark spots on the tail. Finally, mature coloration is reached in the bald eagle’s fifth year. Although bald eagles obtain their adult plumage during their fifth year, they may continue to have a few dark spots on their head and tail for several additional years.

Immature bald eagles are often confused with golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) due to their dark coloration. These birds can be differentiated based on the blotchy white coloration found on the underwing coverts, axillaries, and tails of immature bald eagles. Likewise, bald eagles have longer heads and shorter tails.

If lost, a bald eagle’s flight feathers may take 2 to 3 years to replace.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

Larger FemalesWINGSPAN

178-229 cm. / 70-90 in.BODY MASS

3.2-4.3 kg. / 7.05-9.47 lb.LIFESPAN

15-47 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

17.2 yr.LOCOMOTION

Digitigrade

Images

Taxonomy

The bald eagle is placed in the genus Haliaeetus , comprised of sea eagles.

The bald eagle was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th century work Systema Naturae, under the name Falco leucocephalus.

There are two recognized subspecies of bald eagle. Haliaeetus leucocephalus leucocephalus (Linnaeus, 1766) is the nominate subspecies. It is found in the southern United States and Baja California Peninsula. Haliaeetus leucocephalus washingtoniensis (Audubon, 1827), synonym H. l. alascanus (Townsend, 1897), the northern subspecies, is larger than southern nominate leucocephalus. It is found in the northern United States, Canada and Alaska.

The bald eagle forms a species pair with the white-tailed sea-eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) of Eurasia. This species pair consists of a white-headed and a tan-headed species of roughly equal size, though the white-tailed sea-eagle overall has somewhat paler brown body plumage. The two species fill the same ecological niche in their respective ranges. The pair diverged from other sea-eagles at the beginning of the Early Miocene (c. 10 Ma BP) at the latest, but possibly as early as the Early/Middle Oligocene, 28 Ma BP, if the most ancient fossil record is correctly assigned to this genus.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

AvesORDER

AccipitriformesFAMILY

AccipitridaeGENUS

HaliaeetusSPECIES

leucocephalusSUBSPECIES (2)

H. l. leucocephalus (Southern), H. l. washingtoniensis (Northern)

Etymology

The bald eagle gets both its common and specific scientific names from the distinctive appearance of the adult’s head as mature coloration is reached in the bald eagle’s fifth year. Although bald eagles obtain their adult plumage during their fifth year, they may continue to have a few dark spots on their head and tail for several additional years.

Bald in the English name is from the older usage meaning white rather than hairless, referring to the white head and tail feathers and their contrast with the darker body, as in piebald.

The genus name is New Latin: Haliaeetus (from the Ancient Greek: ἁλιάετος, romanized: haliaetos, lit. sea eagle), and the specific name, leucocephalus, is Latinized (Ancient Greek: λευκός, romanized: leukos, lit. white) and (κεφαλή, kephalḗ, head).

ALTERNATE

American EagleGROUP

Aerie, ConvocationMALE

CockFEMALE

HenYOUNG

Eaglet, Chick, Fledgling

Region

Bald eagles are found throughout North America near large water sources.

These birds are native to Canada, the United States, portions of Mexico, and several islands including Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Populations are especially concentrated in Florida, Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, and near some rivers and lakes in the Midwest. Populations may be limited in Mexico, Arizona, New Mexico, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

This species breeds in Canada, the United States, Mexico, and the French island territories of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

The bald eagle is considered a vagrant in Belize, Bermuda, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. Likewise, there have been reports of bald eagle sightings in Ireland, Sweden, Siberia, Greenland, and northeastern Asia.

EXTANT

Canada, Mexico, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, United StatesVAGRANT

Belize, Bermuda, Ireland, Puerto Rico, Russia, Virgin Islands

Habitat

Bald eagles inhabit forest, shrubland, grassland, wetland, marine neritic, marine intertidal, and artificial aquatic and marine habitats.

Bald eagles typically prefer areas near large water bodies such as sea coasts, coastal estuaries, and inland lakes and rivers. In many areas, these birds are found within three kilometers of a water source.

Although the specific habitats of bald eagles may vary depending on their range, habitat selection depends largely on prey availability, the availability of tall trees, and the degree of human disturbance.

Bald eagles tend to forage much less when disturbed by humans. At times when humans are active in foraging areas, their feeding may be reduced by as much as 35%. As such, these birds avoid human recreation areas and will even forgo feeding if their foraging area is being disturbed by humans. Although food availability is important to habitat selection, bald eagles will inhabit areas further from foraging grounds to avoid human interaction.

Due to food availability, these birds may also be spotted near dams and landfills. For many bald eagle populations, their arrival to their summering grounds marks a time of minimal food availability because many of the water sources may still be frozen. Fortunately, these birds can survive without food for several days. When food is available, bald eagles often gorge and store food in their crop for later digestion.

The bald eagle’s upper elevation limit is 2,000 meters.

There are no extreme fluctuations in the area of occupancy (AOO), the extent of occurrence (EOO), or the number of locations of the bald eagle’s geographic range.

FOREST

Boreal, Temperate, Subtropical/Tropical Mangrove Vegetation Above High Tide LevelSHRUBLAND

TemperateGRASSLAND

TemperateWETLANDS

Permanent Rivers/Streams/Creeks/Waterfalls, Permanent Freshwater LakesMARINE NERITIC

EstuariesMARINE INTERTIDAL

Rocky Shoreline, Sandy Shoreline, Beaches, Sand Bars, Spits, etc., Shingle and Pebble Shoreline and Beaches, TidepoolsARTIFICIAL AQUATIC & MARINE

Water Storage Areas

Co-Habitants

Behavior

Bald eagles are diurnal and spend about 91% of their time resting, 2.6% drinking, 2.3% scavenging, and 1.8% pirating food from others.

Generally, these birds are less active during the winter or when winds are especially high. Likewise, precipitation has a negative impact on their foraging success.

Bald eagles are often solitary, although they pair bond during the nesting season. However, groups of bald eagles may be seen in areas with ample prey and they may roost communally in large groups of up to 400 individuals.

Contrary to popular perception, bald eagles have relatively weak, high-pitched, thin vocalizations, composed of chirps, whistles and harsh chatters. These birds produce three main types of calls, a chatter, which sounds like kwit, kwit, kwit, kwit, kee-kee-kee-kee-ker, a wail, and a peal, which is a long, high-pitched cry used when threats are perceived. Breeding pairs vocalize to each other when returning to their nest.

In addition, bald eagles may communicate threats with a series of visual displays such as head motions, wing motions and crouching.

Bald eagle home range sizes may vary. For instance, populations in Oregon and Washington have home ranges of 6 to 47 square kilometers, with an average of 22 square kilometers; however, a population in Alaska has a territory radius of 0.5 square kilometers. This is believed to be the lower limit for the species. On average, the bald eagle’s home range size is believed to be one to two square kilometers and does not appear to oscillate between breeding and non-breeding seasons.

Bald eagles are considered full migrants. Most populations, specifically those in northern regions, migrate to southern, milder climates annually. The migratory behavior of bald eagles varies across their geographic ranges. For instance, some populations, such as those from Yellowstone, only migrate locally for increased foraging opportunities and many southern populations do not migrate at all. Migratory birds from Canadian populations typically travel south to the United States during the winter, likewise, populations nesting in the Great Lakes region may move toward the Atlantic coast, down to the Chesapeake Bay and populations from northeastern United States and Canada may move south and inland, toward the Appalachian Mountains. Bald eagles from the upper Midwest may travel anywhere from 6 to 151 days to reach their summer range and 15 to 77 days to reach their wintering range. Birds return to their nesting sites at varying times, as soon as weather allows.

Many bald eagle populations use geographic landmarks for navigation, such as mountain ranges and rivers. The Mississippi River, in particular, is a major migratory corridor. Immature birds have much more erratic migratory paths and patterns.

Because the wings of the bald eagle are so powerful, the bird often chooses to soar using slow, heavy wing beats, which allows it to travel far distances. While migrating, bald eagles generally soar, beginning in the late morning and going back to roost before dark.

Migratory birds congregate in areas with food abundances, specifically those areas below the freeze line with open water for hunting.

Bald eagles do not migrate with their mates.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

DiurnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Full Migrant

Diet

As opportunistic, carnivorous foragers, bald eagles have a fairly wide diet, but generally prefer fish. With such a large range, their diet may vary greatly.

Bald eagles are known to eat the following fish: rainbow trout, American eels (Anguilla rostrata), gizzard shads, white catfish (Ameiurus catus), kokanee salmon, rock greenlings, Pacific cod, atka mackerel, largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and chum salmon, among others.

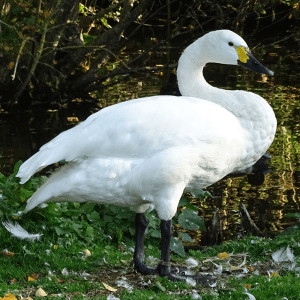

Another large component of their diet includes adult water birds, their nestlings, and their eggs including common murres (Uria aalge), great blue herons (Ardea herodias), snow geese (Anser caerulescens), Ross geese, tundra swans (Cygnus columbianus), northern fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis), auklets, American coots (Fulica americana), and common loons (Gavia immer).

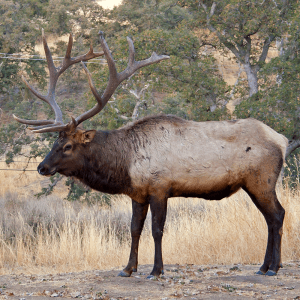

In the winter, their diets often shift to carrion and small mammal prey. Bald eagles may hunt live ground squirrels, Pahranagat Valley montane voles (Microtus montanus), Norway rats, and sea otter pups (Enhydra lutris), among others. Likewise, these birds feed on the carrion of large mammals such as wapiti (Cervus canadensis), moose (Alces alces), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), American bison (Bison bison), wolves, and arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus).

Populations of bald eagles have also been found residing near landfills, consuming human refuse.

In addition to foraging by pursuing live prey or consuming carrion, bald eagles often pirate food from conspecifics and other raptor species, such as ospreys (Pandion haliaetus). In general, younger and smaller birds choose to hunt instead of pirate. When pirating food, eagles may fly, leap, or walk to snatch the food. When walking, bald eagles are somewhat awkward, rocking their bodies as they move.

When hunting, bald eagles perch and observe before descending on their prey and lifting it from the ground with their talons. Bald eagles do not submerge themselves to obtain prey; instead, they use their strong talons to remove fish near the water surface. The speed of a river flow can greatly impact an eagle’s hunting success.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Forager

Reproduction

Bald eagles begin breeding when they are five years old and have a monogamous mating system. These birds are believed to mate for life or until a pair member dies.

Bald eagles perform extremely demonstrative displays when they come together for the breeding season. They perform flight displays with their mates, swooping at each other. During their cart-wheel display, the birds clasp their feet in the air and spin as they plummet towards the ground, letting go before impact. During the breeding season, bald eagles become territorial, vocalizing or chasing conspecifics.

Male and female bald eagles construct their nests together, about 1 to 3 months prior to egg-laying. Nesting dates and the timing of egg-laying vary regionally; in Florida, they begin nest building in September, in Ohio they begin in February, and in Alaska they begin in January.

Bald eagle nests are composed of sticks and can be massive as birds often reuse nests for consecutive years, continually adding to it each year. The largest bald eagle nest on record was found in Florida. It was used for 30 years and weighed two tons when it fell out of a tree. However, nests do not generally last that long. On average, nests in southern Florida and Saskatchewan are used for five years and nests in Alaska are used an average of 13 years.

Bald eagle nests are often located away from human settlements and near water, but they vary based on the population’s location. Generally, bald eagles nest in the canopies of tall, coniferous trees, surrounded by smaller trees, however, in southern Florida, mangroves are used instead. They have also been reported nesting in deciduous trees, on the ground, on cliffs, on cellular phone towers, on electrical poles, and in artificial nesting towers. In the Chesapeake Bay area, bald eagles often roost in oak trees (Quercus) and yellow poplars (Liriodendron tulipifera), generally in woodlots with good canopy cover; however, their large body size prevents their movement through closed canopies.

Bald eagles have a low fecundity and typically produce one brood of one to three eggs per season. Because many of bald eagle eggs do not survive, the birds may have replacement clutches if needed. In California, bald eagles may produce up to 36 young in their lifetime. For males, this is significantly correlated to their body size. Bald eagle eggs are round to oval and are generally whitish. They are generally only exposed while the parents change positions or turn the eggs. This usually lasts for less than one minute at a time, but it may be longer in mild weather.

Eggs are incubated in Florida beginning in October and may last until April, whereas in Yellowstone, eggs are incubated from March until April. Regardless of their geographic location, eggs are generally incubated for about 35 days, followed by an 11 to 12 week nestling period.

Bald eagle populations located further north tend to have shorter breeding seasons and more synchronous nesting periods. Individuals in higher latitudes also often produce larger eggs.

Bald eagles are the largest semi-altricial birds in North America and weigh approximately 60 grams at hatching. They may gain up to 180 grams per day.

Both bald eagle parents care for their offspring, although a larger burden falls on the female. Eggs are brooded by females about three to seven times more frequently than by males and females are present about 90% of the time when brooding young nestlings as opposed to 50% among males. However, most of the food is brought to the nest by males during the first two weeks post-hatching. Eventually, females also provide much of the food.

During the nestling period, young are fed four to five times per day and are brooded constantly until they are about four weeks old. The age at fledging may vary geographically based on climate and food availability, but generally ranges between 8 and 14 weeks. Even after fledging, immature bald eagles may continue their dependency on their parents for an additional 4 to 11 weeks until they are 18 weeks old.

BREEDING SEASON

September-MayBREEDING INTERVAL

1 YearBROOD

1PARENTAL INVESTMENT

Maternal, PaternalNESTING SEASON

September-JanuaryINCUBATION

35 DaysCLUTCH

1-3FLEDGLING

8-14 WeeksINDEPENDENCE

18 WeeksSEXUAL MATURITY

5 Years

Ecology

As a top predator, bald eagles impact all members of their trophic community and their decline and recent population resurgence has impacted many other organisms. Bald eagles are even causing a population decline in common murres (Uria aalge).

For some populations, bald eagles have few predators, allowing them to nest on the ground. However, their eggs and young are often preyed upon by magpies, gulls, ravens, crows, black bears (Ursus americanus), raccoons, bobcats (Lynx rufus), wolverines (Gulo gulo), and arctic foxes (vulpes lagopus). Fully grown adult birds are not often subject to predation.

Bald eagles have been found with Toxoplasma gondii as well as a protozoan, 2 genera of trematodes, 1 genus of acanthocephalan and 7 genera of nematodes.

Bald eagles do not directly have a negative impact on humans. However, as a method of habitat management, buffer zones were established around their nesting sites, which limits human development in some areas.

Bald eagles have been the national symbol of the United States since 1782. As a highly charismatic species, bald eagles draw bird watchers and other nature enthusiasts. In 1989, it was estimated that 20 to 30 million people are involved in bird watching activities, which may equate to approximately 20 billion dollars annually.

PETS/DISPLAY ANIMALS, HORTICULTURE

International

Predators

American Black Bear

Northern Raccoon

Wolverine

Bobcat

Arctic Fox

Conservation

The conservation status of bald eagles has shifted greatly during the recent past.

Bald eagles are currently listed as a species of least concern according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species due to their increasing population and large range. Current and future threats to this species include contamination from coal power plants, Mercury poisoning, and global climate change.

Population

Fortunately, after the ban of the insecticide, DDT, in 1972, the bald eagle’s population has increased dramatically. In 1963, there were an estimated 417 pairs of bald eagles remaining in the continental U.S. As of 1998, there were 5,748 pairs, bringing their productivity back to levels seen prior to DDT usage. In addition, their population in Alaska as of 1993, was between 20,000-25,000 individuals. In Washington State, these birds have had a 700% population increase from 1981 to 2005, growing approximately 9% annually.

FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

The bald eagle’s population was negatively impacted in the early and mid-1900’s by hunting, habitat destruction, and the use of insecticides, such as DDT. Because DDT’s fat soluble properties allow it to accumulate in the fats of organisms as it biologically magnifies, top predators, such as bald eagles, were at great risk. DDT impacts all animals, with impacts such as deformities, neurological damage, and in the case of birds, brittle egg shells and un-hatching eggs.

ACTIONS

The Bald Eagle Protection Act was put into effect in 1940, although the bald eagle’s populations continued to decline throughout the 1950’s and 70’s.

Other factors, such as guidelines regarding the proximity in which humans can develop near bald eagle nests have also positively impacted the species’ population.

As of June 28, 2007 the bald eagle has been removed from the protection of the Endangered Species Act where it had been listed since 1978.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Alderfer, J. (2006). Complete Birds of North America. Washington, D.C: The National Geographic Society.

- Andrews, J. & Mosher, J. (1982, April). Bald eagle nest site selection and nesting habitat in Maryland. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 46(2), 383-390.

- Anthony, R., Estes, J., Ricca, M., Miles, A., & Forsman, E. (2008). Bald eagles and sea otters in the Aleutian Archipelago: Indirect effects of trophic cascades. Ecology, 89(10), 2725-2735.

- Beletsky, L. (2006). Bird Songs. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

- BirdLife International. (2016). Haliaeetus leucocephalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22695144A93492523. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695144A93492523.en.

- Bortolotti, G. (1984a). Physical development of nestling bald eagles with emphasis on the timing of growth events. The Wilson Bulletin, 96(4), 524-542.

- Brown, B. 1993. Winter foraging ecology of bald eagles in Arizona. The Condor, 95-1: 132-138.

- Brown, B., Stevens, L., & Yates, T. (1998). Influences of fluctuating river flows on bald eagle foraging behavior. The Condor, 100(4), 745-748.

- Bryan Jr., A., Hopkins, L., Eldridge, C., Brisbin Jr., I., & Jagoe, C. (2005). Behavior and food habits at a bald eagle nest in inland South Carolina. Southeastern Naturalist, 4(3), 459-468.

- Buehler, D. (2020). Bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), version 1.0. In A.F. Poole & F. B. Gill (Eds.) Birds of the World (1 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.baleag.01

- Buehler, D., Mersmann, T., Fraser, J., & Seegar, J. (1991). Nonbreeding bald eagle communal and solitary roosting behavior and roost habitat on the northern Chesapeake Bay. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 55(2), 273-281.

- Burnie, D. & Wilson, D. (2001, October 10). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World’s Wildlife. New York, NY: DK Publishing.

- Carlson, J., Harmata, A., & Restani, M. (2012). Environmental contaminants in nestling bald eagles produced in Montana and Wyoming. Journal of Raptor Research, 46(3), 274-282.

- Crossley, R. (2011). The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Curnutt, J. & Robertson Jr., W. (1994). Bald eagle nest site characteristics in south Florida. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 58-(2), 218-221.

- del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E. (2017). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

- Dickinson, M. (2017, September 12). Field Guide to the Birds of North America (7 ed.). Washington, D.C: The National Geographic Society.

- Dudley, Karen (1998). Bald Eagles. Austin, TX: Raintree Steck-Vaughn Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8172-4571-9.

- Garrett, M., Watson, J., & Anthony, R. (1993). Bald eagle home range and habitat use in the Columbia River Estuary. Journal of Wildlife Management, 57(1), 19-27.

- Gill, F. B. (2006, October 6). Ornithology. New York, NY: W.H Freeman and Company.

- Grubb, T., Wiemeyer, S., & Kiff, L. (1990). Eggshell thinning and contaminant levels in bald eagle eggs from Arizona, 1977 to 1985. The Southwestern Naturalist, 35-3: 298-301.

- Hansen, A. (1986). Fighting behavior in bald eagles: A test of game theory. Ecology, 67(3), 787-797.

- Harvey, C., Moriarty, P., & Salathe Jr., E. (2012). Modeling climate change impacts on over wintering bald eagles. Ecology and Evolution, 2(3), 501-514.

- Hvenegaard, G., Butler, J., Krystofiak, D. (1989). Economic values of bird watching at Point Pelee National Park, Canada. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 17(4), 526-531.

- ITIS. (2020, June 14). Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Linnaeus, 1766). Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

- Jenkins, J. & Jackman, R. (2006). Lifetime reproductive success of bald eagles in northern California. The Condor, 108, 730-735.

- Kaufman, K. (2005, April 14). Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Keister Jr., G., Anthony, R., & Holbo, H. (1985). A model of energy consumption in bald eagles: An evaluation of night communal roosting. The Wilson Bulletin, 97(2), 148-160.

- Korhel, A. & Clark, T. (1981). Bald eagle winter survey in the Snake River Canyon, Wyoming. The Great Basin Naturalist, 41(4), 461-464.

- Loomis, J. & White, D. (1996). Economic benefits of rare and endangered species: Summary and meta-analysis. Ecological Economics, 18, 197-206.

- Mandernack, B., Solensky, M., Martell, M., & Schmitz, R. (2012). Satellite tracking of bald eagles in the upper Midwest. Journal of Raptor Research, 46(3), 258-273.

- McCarthy, K., DeStefano, S., & Laskowski, T. (2010). Bald eagle predation on common loon eggs. Journal of Raptor Research, 44(3), 249-251.

- McClelland, B., Young, L., McCelelland, P., Crenshaw, J., Allen, H., & Shea, D. (1994). Migration ecology of bald eagles from autumn concentrations in Glacier National Park, Montana. Wildlife Monographs, 125, 3-61.

- Millsap, B., Breen, T., McConnell, E., Steffer, T., Phillips, L., Douglas, N., & Taylor, S. (2004). Comparative fecundity and survival of bald eagles fledged from suburban and rural natal areas in Florida. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 68(4), 1018-1031.

- Norman, D., Breault, A., & Moul, I. (1989). Bald eagle incursions and predation at great blue heron colonies. Colonial Waterbirds, 12(2), 215-217.

- Parrish, J., Marvier, M., Paine, R. (2001). Direct and indirect effects: Interactions between bald eagles and common murres. Ecological Applications, 11(6), 1858-1869.

- Rockwell, D. (1998). The Nature of North America: A Handbook to the Continent. New York, NY: Berkley Books.

- Saalfeld, S. & Conway, W. (2010). Local and landscape habitat selection of nesting bald eagles in east Texas. Southeastern Naturalist, 9(4), 731-742.

- Schirato, G. & Parson, W. (2006). Bald eagle management in urbanizing habitat of Puget Sound, Washington. Northwestern Naturalist, 87(2), 138-142.

- Sibley, D. (2003). The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Starr, C., Taggart, R., Evers, C., & Starr, L. (2012, January 1). Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (13 ed.). Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning.

- Stalmaster, M. & Kaiser, J. (1998). Effects of recreational activity on wintering bald eagles. Wildlife Monographs, 137, 3-46.

- Siciliano Martina, L. (2013). Haliaeetus leucocephalus. Animal Diversity Web.

- Szabo, K., Mense, M., Lipscomb, T., Felix, K., & Dubey, J. (2004). Fatal Toxoplasmosis in a bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). The Journal of Parasitology, 90(4), 907-908.

- Thompson, C., Nye, P., Schmidt, G., & Garcelon, D. (2005). Foraging ecology of bald eagles in a fresh water tidal system. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 69(2), 609-617.

- Watts, B. D. & Duerr, A. (2010). Nest turnover rates and list-frame decay in bald eagles: Implications for the national monitoring plan. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(5), 940-944.

- Watts, B. D., Markham, A., & Byrd, M. A. (2006). Salinity and population parameters of bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) in the lower Chesapeake Bay. The Auk, 123(2), 393-404.

- Watts, B. D., Therres, G. D., & Byrd, M. A. (2008). Recovery of the Chesapeake Bay bald eagle nesting populations. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 72(1), 152-158.

- The Wikimedia Foundation. (2020, June 14). Bald Eagle. Wikipedia.

- Wink, M (1996). A mtDNA phylogeny of sea eagles (genus Haliaeetus) based on nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b gene. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 24(7–8), 783–791. doi:10.1016/S0305-1978(97)81217-3.