PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The barn swallow is the most widespread swallow species and can be found in close proximity to humans all around the world. These small, distinctive, passerine birds are aerial foragers and catch their insectivorous prey while flying. Socially monogamous, they build nests and raise young in large colonies.

Physiology

Barn swallows are small, distinctive, passerine birds. They range in size from 14.6 to 19.9 centimeters long (5.7-7.8 inches), with a wingspan of 31.8 to 34.5 centimeters (12.5-13.56 inches). They weigh between 16 and 22 grams (0.6-0.8 ounces).

The barn swallow has a long, deeply forked tail. The outer tail feathers are elongated, ranging from 2-7 centimeters, or 0.8-2.8 inches, giving the distinctive deeply forked swallow tail. There is a line of white spots across the outer end of the upper tail.

The barn swallow is metallic steel blue-black across the back and upperparts and pale beige on the stomach. It has a rufous light brown forehead, chin, and throat which are separated from the off-white underparts by a broad dark blue breast band.

Males and females are similar in appearance, though females tend to be less vibrantly colored and have shorter outer tail-streamers. The blue of the female’s upperparts and breast band is less glossy, and the underparts are paler.

Asymmetry of physical characteristics in barn swallows tends to be transmitted to the young in distinct parent to offspring patterns. Tail asymmetry tends to pass from father to son and from mother to daughter. Alternatively, wing asymmetry does not appear to transfer at all on a reliable basis from parent to offspring.

The juvenile barn swallow is browner and has a paler rufous face and whiter underparts. It also lacks the long tail streamers of the adult.

The distinctive combination of a red face and blue breast band render the adult barn swallow easy to distinguish from the African Hirundo species and from the welcome swallow (Hirundo neoxena) with which its range overlaps in Australasia. In Africa, the short tail streamers of the juvenile barn swallow invite confusion with juvenile red-chested swallow (Hirundo lucida), but the latter has a narrower breast band and more white in the tail.

The average lifespan of barn swallows is 4 years. Barn swallows of 8 years of age have been documented, but these are considered the exception. Survival prospects and longevity appear to increase with tail length and wing and tail symmetry.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

Vibrant Males with Longer Outer Tail-StreamersBODY LENGTH

14-20 cm. / 5-8 in.WINGSPAN

31-35 cm. / 12-14 in.OUTER TAIL FEATHERS

2-7 cM. / 0.8-2.8 in.BODY MASS

16-22 g. / 0.6-0.8 oz.LIFESPAN

4 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

3.9 yr.LOCOMOTION

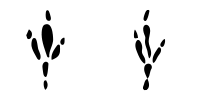

Digitigrade

Images

Taxonomy

Six subspecies of the barn swallow are generally recognized, all of which breed across the Northern Hemisphere. Four are strongly migratory, and their wintering grounds cover much of the Southern Hemisphere as far south as central Argentina, the Cape Province of South Africa, and northern Australia.

In eastern Asia, a number of additional or alternative forms have been proposed, including saturata by Robert Ridgway in 1883, kamtschatica by Benedykt Dybowski in 1883, ambigua by Erwin Stresemann, and mandschurica by Wilhelm Meise in 1934. There are uncertainties over the validity of these forms.

H. r. rustica, the nominate European subspecies, breeds in Europe and Asia, as far north as the Arctic Circle, south to North Africa, the Middle East and Sikkim, and east to the Yenisei River. It migrates on a broad front to winter in Africa, Arabia, and the Indian subcontinent. The barn swallows wintering in southern Africa are from across Eurasia to at least 91°E, and have been recorded as covering up to 11,660 kilometers (7,250 miles) on their annual migration. The nominate European subspecies was the first to have its genome sequenced and published.

H. r. transitiva was described by Ernst Hartert in 1910. It breeds in the Middle East from southern Turkey to Israel and is partially resident, though some birds winter in East Africa. It has orange red underparts and a broken breast band.

H. r. savignii, the resident Egyptian subspecies, was described by James Stephens in 1817 and named for French zoologist Marie Jules César Savigny. It resembles transitiva, which also has orange-red underparts, but savignii has a complete broad breast band and deeper red hue to the underparts.

H. r. gutturalis, described by Giovanni Antonio Scopoli in 1786, has whitish underparts and a broken breast band. Breast chestnut and lower underparts more pink-buff. The populations that breed in the central and eastern Himalayas have been included in this subspecies, although the primary breeding range is Japan and Korea. The east Asian breeders winter across tropical Asia from India and Sri Lanka east to Indonesia and New Guinea. Increasing numbers are wintering in Australia. It hybridises with H. r. tytleri in the Amur River area. It is thought that the two eastern Asia forms were once geographically separate, but the nest sites provided by expanding human habitation allowed the ranges to overlap.

H. r. gutturalis is a vagrant to Alaska and Washington, but is easily distinguished from the North American breeding subspecies, H. r. erythrogaster, by the latter’s reddish underparts.

H. r. tytleri, first described by Thomas Jerdon in 1864, and named for British soldier, naturalist and photographer Robert Christopher Tytler, has deep orange-red underparts and an incomplete breast band. The tail is also longer. It breeds in central Siberia south to northern Mongolia and winters from eastern Bengal east to Thailand and Malaysia.

H. r. erythrogaster, the North American subspecies described by Pieter Boddaert in 1783, differs from the European subspecies in having redder underparts and a narrower, often incomplete, blue breast band. It breeds throughout North America, from Alaska to southern Mexico, and migrates to the Lesser Antilles, Costa Rica, Panama and South America to winter. A few may winter in the southernmost parts of the breeding range. This subspecies funnels through Central America on a narrow front and is therefore abundant on passage in the lowlands of both coasts.

The short wings, red belly, and incomplete breast band of H. r. tytleri are also found in H. r. erythrogaster, and DNA analyses show that barn swallows from North America colonised the Baikal region of Siberia, a dispersal direction opposite to that for most changes in distribution between North America and Eurasia.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

AvesORDER

PasseriformesFAMILY

HirundinidaeGENUS

HirundoSPECIES

rusticaSUBSPECIES (6)

H. r. rustica (European), H. r. erythrogaster (North American), H. r. guttyrakus (Asian), H. r. savignii (Egyptian), H. r. transitiva (Middle Eastern), H. r. tytleri (Asian)

Etymology

The term swallow is used colloquially in Europe as a synonym for the barn swallow. In Anglophone Europe, the barn swallow is just called the swallow. In Northern Europe, the barn swallow is the only common species called a swallow rather than a martin.

The barn swallow’s scientific name is Hirundo rustica. Hirundo is the Latin word for swallow and rusticus translates to of the country.

Most male birds are called cocks, while most female birds are called hens.

Young birds are often referred to as chicks or nestlings.

ALTERNATE

Common Swallow, European Swallow, SwallowGROUP

Colony, KettleMALE

CockFEMALE

HenYOUNG

Chick, Nestling

Region

Barn swallows are native in all the biogeographic regions except Australia and Antarctica. The barn swallow is the most widespread species of swallow in the world and is found in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

The breeding range of barn swallows includes North America, northern Europe, northcentral Asia, northern Africa, the Middle East, southern China, and Japan.

This species breeds across the Northern Hemisphere from sea level to 2,700 meters (8,900 feet), but to 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) in the Caucasus and North America, and it is absent only from deserts and the cold northernmost parts of the continents.The breeding range of barn swallows includes North America, northern Europe, northcentral Asia, northern Africa, the Middle East, southern China, and Japan.

Over much of its range, the barn swallow avoids towns, and in Europe is replaced in urban areas by the northern house martin (Delichon urbicum). However, in Honshū, Japan, the barn swallow is a more urban bird, with the red-rumped swallow (Cecropis daurica) replacing it as the rural species.

In winter, the barn swallow is cosmopolitan in its choice of habitat, avoiding only dense forests and deserts. It is most common in open, low vegetation habitats, such as savanna and ranch land, and in Venezuela, South Africa, and Trinidad and Tobago it is described as being particularly attracted to burnt or harvested sugarcane fields and the waste from the cane. European birds winter in sub-Saharan Africa, although some individuals winter in southern and western Europe each year. Birds breeding in North America winter in South America whilst birds breeding in East Asia winter in South Asia, Indonesia, and Micronesia.

The barn swallow has been recorded as breeding in the more temperate parts of its winter range, such as the mountains of Thailand and in central Argentina.

Migration of barn swallows between Britain and South Africa was first established on December 23rd, 1912 when a bird that had been ringed by James Masefield at a nest in Staffordshire, was found in Natal. As would be expected for a long-distance migrant, this bird has occurred as a vagrant to such distant areas as Hawaii, Bermuda, Greenland, Tristan da Cunha, the Falkland Islands, and even Antarctica

EXTANT (BREEDING)

Afghanistan, Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bhutan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, China, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Georgia, Gibraltar, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Nepal, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Kingdom, United States, Uzbekistan, VietnamEXTANT (NON-BREEDING)

Costa Rica, Guam, Jamaica, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Uruguay, Virgin IslandsEXTANT (PASSAGE)

Canada, Gaudeloupe, Nicaragua, Palestine, Qatar, South SudanVAGRANT

Antarctica, Cocos Islands, Greenland, Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, Svalbard and Jan MayenUNCERTAIN

Macao, Saint Barthélemy

Habitat

Barn swallows are very adaptable birds and breed in a wide range of climates over a wide altitudinal range. It is a bird of open country that normally uses man-made structures to breed and consequently has spread with human expansion. They prefer open country, such as farmland, where buildings provide nesting sites and where water is nearby, but can nest anywhere with open areas for foraging, a water source, and a sheltered ledge.

Barn swallows seek out open habitats of all types, including savanna, shrubland, grassland, inland wetlands, artificial terrestrial habitats, artificial aquatic and marine habitats, and agricultural areas. They are commonly found in barns or other outbuildings. It is primarily a rural species in Europe and North America, whilst in north Africa and Asia it often breeds in towns and cities. In urban areas in Europe it is superseded by the house martin (Delichon urbicum).

Barn swallows will build nests in barns or similar structures, under bridges, the eaves of old houses, and boat docks, as well as in rock caves and even on slow-moving trains. Barn swallows generally nest below 3000-meter elevation.

In the absence of suitable roost sites, barn swallows may sometimes roost on wires where they are more exposed to predators. Individual birds tend to return to the same wintering locality each year and congregate from a large area to roost in reed beds. These roosts can be extremely large; one in Nigeria had an estimated 1.5 million birds. These roosts are thought to be a protection from predators, and the arrival of roosting birds is synchronized in order to overwhelm predators like African hobbies (Falco cuvierii).

SAVANNA

DrySHRUBLAND

Subtropical/Tropical DryGRASSLAND

Temperate, Subtropical/Tropical DryWETLANDS

Permanent Rivers/Streams/Creeks/Waterfalls, Bogs, Marshes, Swamps, Fens, Peatlands, Permanent Freshwater Lakes, Seasonal/Intermittent Freshwater Lakes, Permanent Freshwater Marshes/PoolsARTIFICIAL/TERRESTRIAL

Arable Land, Pastureland, Rural Gardens, Urban AreasARTIFICIAL/AQUATIC & MARINE

Canals & Drainage Channels, Ditches

Co-Habitants

Bobcat

Common Grackle

Boat-Tailed Grackle

Brown-Headed Cowbird

American Bullfrog

Brown Rat

Northern Raccoon

Rusty-Spotted Cat

American Kestrel

Eastern Screech-Owl

Sharp-Shinned Hawk

Welcome Swallow

Cooper’s Hawk

Red-Chested Swallow

Osprey

Behavior

Barn swallows are diurnal.

Barn swallows are often seen in large social groups sitting on telephone wires or other elevated structures. Barn swallows also nest colonially, probably as a result of the distribution of high quality nest sites. Within a colony, barn swallows defend a territory around their nest. In European barn swallows, these territories range in size from about 4 to 8 square meters.

The barn swallow is susceptible to changes in climate with bad weather in the wintering areas as well as the breeding grounds affecting breeding success. As such, the barn swallow is migratory. European birds winter in sub-Saharan Africa, although some individuals winter in southern and western Europe each year. Birds breeding in North America winter in South America whilst birds breeding in East Asia winter in South Asia. While migrating, barn swallows tend to fly over open areas, often near water or along mountain ridges.

Barn swallows use vocalizations and body language, such as postures and movements, to communicate. Barn swallows sing, both individually and as a group. Barn swallows have individual songs and often sing as a chorus. They have a wide variety of calls used in different situations, from predator alarm calls, to courtship calls, and calls of young in nests. Nestlings give off a faint chirp while begging for food. Barn swallows also make clicking noises, which they create by snapping their jaws together.

Barn swallows usually give alarm calls when predators come near. They mainly escape predators by being swift and agile in flight and by building their nests in places that are difficult for predators to reach.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

DiurnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Full Migrant

Diet

Barn swallows are aerial foraging insectivores and feed almost entirely on flying insects. Flies, grasshoppers, crickets, dragonflies, beetles, moths, and other flying insects make up 99% of their diet.

Barn swallows catch most of their prey while in flight, and are able to feed their young at the nest while flying.

Barn swallows forage opportunistically. They have been observed following tractors and plows in order to catch the insects that are disturbed by the machinery.

A study in West Virginia found that barn swallows foraged within 1.2 kilometers of their nests. In Europe, barn swallows foraged within 500 meters of their nest.

Barn swallows drink water by skimming the surface of a body of water while flying.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Forager

Reproduction

Like all swallows, barn swallows are socially monogamous. However, extra-pair copulations are common, making this species genetically polygamous.

The barn swallow’s breeding season is usually from May to August, but this varies greatly with location. Breeding pairs form each spring after arrival on the breeding grounds. Pairs re-form each spring, though pairs that have nested together successfully may mate together for several years.

Several studies have researched sexual selection in barn swallows.

Males try to attract females by spreading their tails to display them and singing.

Female barn swallows have been documented selecting for symmetrical wings and tails in potential mates. Males exhibiting greater symmetry acquired mates more quickly than did asymmetric males. Asymmetry can result from genetic factors such as inbreeding or mutations as well as from environmental stress such as food deficiency, parasite infestation, or the presence of pathogens. Asymmetry of physical characteristics in barn swallows tends to be transmitted to the young in distinct parent to offspring patterns. Tail asymmetry tends to pass from father to son and from mother to daughter. Alternatively, wing asymmetry does not appear to transfer at all on a reliable basis from parent to offspring. Individuals affected by these factors not only exhibited asymmetry, but also decreased strength and longevity. Therefore, females that selected symmetrical mates would presumably be selecting superior mates.

In addition to selecting for symmetry, females also tend to select males with longer tail feathers. A connection between the tail length of male barn swallows and their offspring’s vitality and longevity has been observed. Males with longer tail feathers exhibit traits of greater longevity which is passed on to their offspring. Females thus gain an indirect fitness benefit from this form of selection, as longer tail feathers indicate a genetically stronger individual who will produce offspring with enhanced vitality. Individuals with longer tails have also been observed to demonstrate greater disease resistance than their short-tailed counterparts. There is also evidence that males select female mates with long tails.

Un-mated adults often associate with a breeding pair for up to an entire season. Though these helpers do not usually feed the young, they may help with nest defense, nest building, incubation, and brooding. Helpers are predominantly male, and may succeed in mating with the resident female, leading to polygyny.

Both sexes of barn swallow help build the nest, which measures a cup or half-cup. The nest’s exterior is made from mud pellets mixed with fibers such as dry grass, straw, and horsehair. The nest is lined with dry grass and white feathers. Originally nests were built in caves or on cliffs but now they’re almost always on artificial structures.

In North America, introduced house sparrows (Passer domesticus) are serious nest-site competitors, taking over nests and destroying eggs and nestlings.

Although all swallows are socially monogamous, barn swallows differ from most swallow species in the sharing of parental care. In North America, both parents incubate the eggs, which hatch in 13 to 15 days. However, females provide more parental care than do males.

Barn swallows usually raise two broods of chicks each summer. The female lays a clutch of two to seven eggs, with an average of five.

The chicks are naked and helpless when they hatch. Both parents feed and protect the chicks, as well as remove fecal sacs from the nest. During the nestling period, barn swallow parents may feed their nestlings up to 400 times per day. Barn swallows feed their chicks insects compressed into a pellet, which is transported to the nest in the parent’s throat. Juveniles from the first brood of the season have even been observed assisting their parents in feeding a second brood.

The nestlings remain in the nest for about 20 days before fledging. When barn swallows are handled by humans they tend to attempt to fledge at least a day too early. The parents continue to care for the chicks for up to a week after fledging, feeding them and leading them back to the nest to sleep. By two weeks after fledging, the barn swallow chicks have dispersed and often travel widely to other barn swallow colonies.

Young barn swallows are able to breed in the first breeding season after they have hatched. Generally, young barn swallows do not produce as many eggs as do older birds.

BREEDING SEASON

May-AugustBREEDING INTERVAL

1 YearPARENTAL INVESTMENT

Maternal, PaternalINCUBATION

13-17 DaysCLUTCH

2-7FLEDGLING

20 DaysINDEPENDENCE

2 WeeksSEXUAL MATURITY

1 Year

Ecology

Barn swallows eat an enormous amount of insects and are very important in the control of their populations. They are quite effective in reducing insect pest populations.

Barn swallows can also serve as an indicator or trigger organism, indicating possible environmental trouble, as declines in their relatively abundant numbers may precede other more obvious effects of environmental stress.

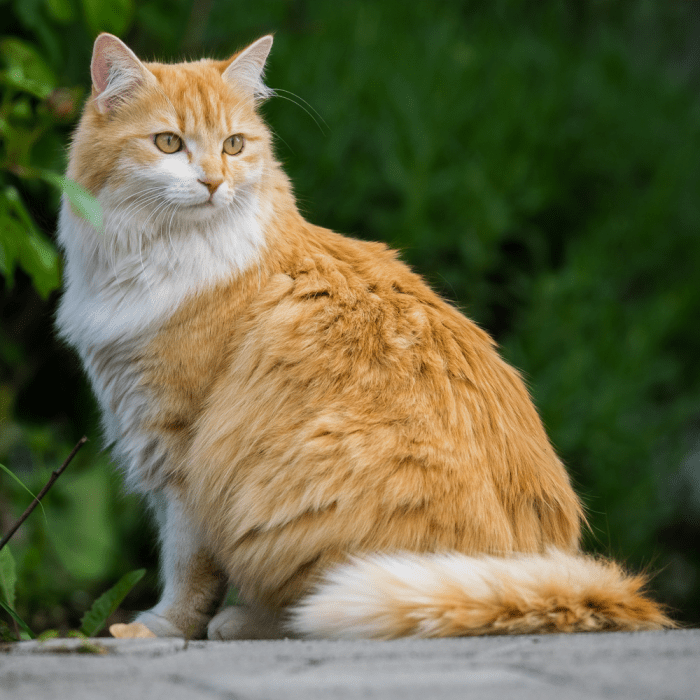

Barn swallows are also a useful food source for many predators. American kestrels (Falco sparverius) and other hawks, such as sharp-shinned hawks (Accipiter striatus) and Cooper’s hawks (Accipiter cooperii), eastern screech owls (Megascops asio), gulls (Laridae), common grackles (Quiscalus quiscula), boat-tailed grackles (Quiscalus major), brown rats (Rattus norvegicus), squirrels (Sciuridae), weasels (Mustela), Northern raccoons (Procyon lotor), bobcats (Lynx rufus), domestic cats (Felis catus), snakes (Serpentes), American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus), fish (Actinopterygii), and fire ants (Formicidae) are predators of barn swallows.

Most predators of barn swallows attack the nestlings, but hawks, falcons, and owls tend to hunt adults.

Barn swallows frequently engage in a symbiotic relationship with ospreys (Pandion haliaetus), coexisting in a single nesting area to the mutual benefit of both species. Barn swallows will nest either below a much larger osprey nest or in a portion of an abandoned osprey nest. By nesting near an osprey population, the barn swallows receive protection from birds of prey, which are driven away from the nests by the much larger ospreys. In return, ospreys are alerted to the presence of these predators by the barn swallows which give alarm calls when predators are nearby.

Although incidents of cowbirds parasitizing barn swallow nests are rare, they have been documented. A 1994 observation of 67 barn swallow nests found two of these nests to contain brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater) eggs, which were laid by the parent cowbird and left in the barn swallow nest in a parasitic fashion for the barn swallows to raise. Each of these nests contained one cowbird egg and both eggs were incubated by the barn swallows along with their own eggs. However, only one of the cowbird eggs hatched. The single cowbird hatchling fledged normally, thus demonstrating that barn swallows are capable of acting as cowbird hosts.

The barn swallow lives in close association with humans and its insect-eating habits mean that it is tolerated by humans. This acceptance was reinforced in the past by superstitions regarding the bird and its nest.

There are frequent cultural references to the barn swallow in literary and religious works due to both its living in close proximity to humans and its annual migration. The barn swallow is the national bird of Austria and Estonia.

Some humans feel that barn swallow nests are a nuisance, and are unsightly when they are attached to buildings and other man-made structures. Large colonies in urban areas can also create detrimental cleanliness and health issues for humans. Finally, salmonella can be transmitted through barn swallow feces, posing a threat to livestock that live in close proximity to barn swallow colonies. As such, barn swallow nests are sometimes removed as a nuisance.

SPORT HUNTING/SPECIMEN COLLECTING

Local, NationalFOOD

Local, NationalPETS/DISPLAY ANIMALS, HORTICULTURE

International

Predators

Bobcat

Boat-Tailed Grackle

Common Grackle

American Kestrel

Brown-Headed Cowbird

Brown Rat

Eastern Screech-Owl

Cooper’s Hawk

Sharp-Shinned Hawk

Human

Northern Raccoon

Cat

American Bullfrog

Osprey

Conservation

Due to its extremely large range, not rapidly decreasing population trend, and extremely large population size, the barn swallow is evaluated as Least Concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

Population

Barn swallows continue to be widespread and common throughout their range. The barn swallow’s global population is estimated at about 190,000,000 individuals.

The European population is estimated at 29,000,000-48,700,000 pairs, which equates to 58,000,000-97,400,000 mature individuals. Europe forms approximately 20% of the global range, so a very preliminary estimate of the global population size is 290,000,000-487,000,000 mature individuals, although further validation of this estimate is needed.

National population estimates include: c.10,000-1 million breeding pairs and > c.1,000 individuals on migration in China; c.10,000- 100,000 breeding pairs, > c.10,000 individuals on migration and c.1,000 individuals on migration in Korea; c.10,000-1 million breeding pairs, > c.1,000 individuals on migration and c.50-1,000 wintering individuals in Japan and c.10,000-100,000 breeding pairs and c.1,000-10,000 individuals on migration in Russia.

The barn swallow has undergone a small or statistically insignificant decrease over the last 40 years in North America. Trends for the European population between 1980 and 2013 have been stable, howevever, the European population size is estimated to be decreasing by less than 25% in 11.7 years, or three generations.

The barn swallow has an extremely large range, and is not endangered, although there may be local population declines due to specific threats. The barn swallow does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence <20,000 kilometers squared combined with a declining or fluctuating range size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of locations or severe fragmentation).

Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over ten years or three generations).

The population size is extremely large, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population size criterion (10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure).

MATURE INDIVIDUALS

290,000,000-487,000,000FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

The main threat to the barn swallow is the intensification of agriculture. Barn swallow populations are generally considered to be stable and sufficiently extensive. However, declines in the amount of acreage devoted to agriculture in recent years have resulted in reduced barn swallow numbers. This can be attributed to a reduction in habitat as the barns and outbuildings which once housed barn swallows, give way to more urban settings.

Changes in farming practices such as the abandonment of traditional milk and beef production have resulted in a loss of suitable foraging areas. In addition, the reduction in food supply. Insects attracted by the presence of livestock and the ideal surrounding habitat are the primary food source for barn swallows living in agricultural areas. Locations where farming has ceased exhibit a 50% reduction in insect populations. Intensive livestock rearing, improved hygiene, land drainage, and the use of herbicides and pesticides all reduce the numbers of insect prey available.

Lastly, suitable nest sites are often scarcer on modern farms.

AGRICULTURE & AQUACULTURE

Livestock Farming & RanchingBIOLOGICAL RESOURCE USE

Hunting & Trapping Terrestrial AnimalsNATURAL SYSTEM MODIFICATIONS

Dams & Water Management/UseINVASIVE & OTHER PROBLEMATIC SPECIES, GENES, & DISEASES

Invasive Non-Native/Alien Species/DiseasesPOLLUTION

Agricultural & Forestry EffluentsCLIMATE CHANGE & SEVERE WEATHER

Temperature Extremes

ACTIONS

There are currently no known conservation measures for the barn swallow within Europe.

Large areas of suitable habitat need to be maintained for this species, through the continuation and promotion of low-intensity, traditional farming. In particular, this requires extensive livestock rearing, a reduction in pesticide use and the preservation of wetland areas and waterbodies. Long-term monitoring and further research into the impacts of climatic variation is also needed.

Nesting can be encouraged by providing wooden ledges or artificial nest cups made of cement and sawdust or papier maché.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- BirdLife International. (2015). European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Barker, E., Ewins, P., & Miller, J. (1994). Birds breeding in or beneath osprey nests. Wilson Bulletin, 106, 743-750.

- Brown, C. R. & Brown, M. B. (1999). Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica). In A. Poole & F. Gill (Eds.), The Birds of North America (Vol. 452) (pp. 1-32). Philadelphia, PA: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Bolzern, A., Moller, A., Saino, N. (1997). Immunocompetence, ornamentation, and viability of male barn swallows. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94, 54-552.

- Brazil, M. (2009). Birds of East Asia: Eastern China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Eastern Russia. London, U.K.: Christopher

- Helm.

- Cocker, M. & Mabey, R. (2005, September 1). Birds Britannica. London, U.K.: Random House UK. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- De Lope, F. & Moller, A. P. (1993). Female reproductive effort depends on the degree of ornamentation. Evolution, 47(4), 1152-1161.

- Dekker, R. W. R. J. (2003, October). Type specimens of birds. Part 2. NNM Technical Bulletin, 6, 20.

- del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E. (2017). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

- Dickinson, E. C. & Dekker, R. (2001). Systematic notes on Asian birds. 13. A preliminary review of the Hirundinidae. Zoologische Verhandelingen, Leiden, 335, 127–144. ISSN 0024-1652.

- Dickinson, E. C., Eck, S., & Milensky, C. M. (2002). Systematic notes on Asian birds. 31. Eastern races of the barn swallow Hirundo rustica Linnaeus, 1758. Zoologische Verhandelingen, Leiden, 340, 201–203. ISSN 0024-1652.

- Edenius, L. (2019, August 13). XC492313. Xeno-Canto.

- European Bird Census Council (EBCC). (2015). Pan-European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme. European Bird Census Council.

- Formenti, G., Chiara, M., Poveda, L., Francoijs, K.-J., Bonisoli-Alquati, A., Canova, L., Gianfranceschi, L., Horner, D. S., & Saino, N. (2019, January). SMRT long reads and direct label and stain optical maps allow the generation of a high-quality genome assembly for the European barn swallow (Hirundo rustica rustica). GigaScience, 8(1), doi:10.1093/gigascience/giy142. PMC 6324554. PMID 30496513.

- Gill, F. & Wright, M. (2006, August 20). Birds of the World: Recommended English Names Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12827-6

- Hebblethwaite, M., Shields, W. (1990). Social influences on barn swallow foraging in the Adirondacks: A test of competing hypotheses. Animal Behavior, 39, 97-104.

- Hilty, S. L. (2003, January 1). Birds of Venezuela (2 ed.). London, U.K.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-7136-6418-8.

- McWilliams, G. (2000, January 4). The Birds of Pennsylvania. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Moller, A. P. (1991). The preening activity of swallows, Hirundo rustica, in relation to experementally manipulated loads of haematophagous mites. Animal Behavior, 42, 251-260.

- (1994, June 1). Patterns of fluctuating asymmetry and selection against asymmetry. Evolution, 48(3), 658-671.

- (1994, July). Male ornament size as a reliable cue to enhanced offspring viability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 91, 6929-6932.

- (1995). Sexual selection in the barn swallow Hirundo rustica: Female tail ornaments. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 8, 3-19.

- Moore, P. (2001). Dairy declines hard to swallow. Nature, 411, 904-905.

- Perrins, C. (1989). Encyclopedia of Birds. England: Equinox Ltd.

- Rasmussen, P. C. & Anderton, J. C. (2005, June 30). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-87334-67-2.

- Rich, T. D., Beardmore, C. J., Berlanga, H., Blancher, P. J., Bradstreet, M. S. W., Butcher, G. S., Demarest, D. W., Dunn, E. H., Hunter, W. C., Inigo-Elias, E. E., Martell, A. M., Panjabi, A. O., Pashley, D. N., Rosenberg, K. V., Rustay, C. M., Wendt, J. S., Will, T. C. (2004). Partners in Flight: North American Landbird Conservation Plan. Itacha, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Roth, C. (2002). Hirundo rustica. Animal Diversity Web.

- Sibley, D. (2007, August 15). The North American Bird Guide. Christopher Helm Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1-873403-98-3.

- Snow, D. W. & Perrins, C. M. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic: Passerines (Vol. 2). Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Stiles, G. & Skutch, A. (2003). A guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2287-4.

- Svensson, L., Mullarney, K., & Zetterstrom, D. (2010, March 1). Collins Bird Guide. London, U.K.: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-219728-1.

- Terres, J. K. (1991, September 27). The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Tucker, G. M. & Heath, M. F. (1994). Birds in Europe: Their Conservation Status (1 ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: BirdLife International.

- Turner, A. & Christie, D. A. (2017). Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E. (Eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

- Turner, A. & Rose, C. (1989, August 24). A Handbook to the Swallows and Martins of the World. London, U.K.: Christopher Helm.

- Vaurie, C. (1951). Notes on some Asiatic swallows. American Museum Novitates, 1529, 1–47. hdl:2246/3915.

- The Wikimedia Foundation. (2019, September 18). Barn swallow. Wikipedia.

- Wolfe, D. (1994). Brown-headed cowbirds fledged from barn swallow and American robin nests. Wilson Bulletin, 106, 764-767.

- Zink, R. M., Pavlova, A., Rohwer, S., & Drovetski, S. V. (2006, March 7). Barn swallows before barns: Population histories and intercontinental colonization. Journal of the Royal Society: Proceedings B, 273(1591), 1245–1251.