PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The bearded vulture is an especially large vulture that feeds primarily on bones. They have an extremely high acid content within their stomachs that allows them to consume large bones whole and digest them within 24 hours. As scavengers, they soar 300-4,500 meters in the air, waiting for other predators to take down prey and pick the bones clean before they swoop in to consume the rest of the carcass. By disposing of rotting remains, these birds help keep the ecosystem clear of disease. Because these avians reside across three continents, Africa, Asia, and Europe, they are wide-spread and listed as Near Threatened. However, their populations are rapidly decreasing in Europe, where they are considered endangered.

Physiology

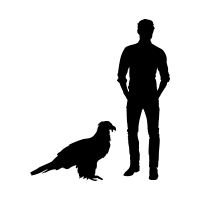

Bearded vultures are extremely large, distinctive vultures that range in weight from 4.5 to 7 kilograms. They have a total length between 94 and 125 centimeters and a much longer wingspan of 228 to 283 centimeters.

Male and female bearded vultures are very similar in appearance, but females are slightly larger on average.

Unlike most vultures, bearded vultures lack an entirely bald head and feature an almost shaggy, fully feathered neck and legs. Increased featheration is likely due to differences in diet as bearded vultures subsist mainly on bones while most vultures primarily consume carrion.

Bearded vultures are so named for the long, broad, black bristles that grow from the base of the bill that resemble a beard.

Adult bearded vultures are a dark gray-black or gray-blue in color, with a slightly darker tail and lighter shaft-streaks. Each side of the face is separated by a thick black band around the eyes, with long, broad black bristles at the base of the bill that resemble a beard. The forehead is a creamy-white, yellow color, while the rest of the head is a maize color, often becoming more of a rusty red-orange rufous color on the neck and abdomen that is darker on the throat and neck. The face is variably black-streaked with black ear-tufts. The chest is speckled with black streaks and broken spots.

The rufous coloration of the bearded vulture is not natural, but instead cosmetic. This orange color is acquired by dusting or bathing in iron-rich spring water and varies in shade depending on the amount of time an individual baths. The red color can be washed or brushed off to reveal natural white feathers.

The bearded vulture is a long-lived bird of prey with a mean lifespan of 21.4 years in the wild. In captivity, they have lived for over 45 years.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

Larger FemalesBODY HEIGHT

93-125 cm. / 37-49 in.WINGSPAN

2.28-2.83 m. / 7.9-9.25 ft.BODY MASS

4-7 kg. / 2-16 lb.LIFESPAN

21-45 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

17.8 yr.LOCOMOTION

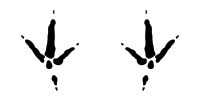

Digitigrade

Images

Taxonomy

The bearded vulture is traditionally considered an Old World vulture and actually forms a minor lineage of Accipitridae together with the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), its closest living relative.

There are up to thirteen different subspecies of bearded vultures, though most lack sufficient grounds to be wholly considered. The Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) currently recognizes three subspecies of bearded vulture.

Gypaetus barbatus barbatus is restricted to northwest Africa, while Gypaetus barbatus meridionalis can be found throughout eastern Africa and the nation of South Africa. Gypaetus barbatus aureus can be found throughout Europe and Asia, while Gypaetus barbatus altaicus are found only in the Himalayas and mountains of central Asia.

The subspecies of Gypaetus barbatus have defining physical appearances as adults that distinguish them from one another. Gypaetus barbatus barbatus possesses joined black eye-patches, black face-streaks, a partially or fully black gorget, and a completely feathered tarsi. Gypaetus barbatus aureus is slightly larger and more prominently marked than its northwest African relative. Gypaetus barbatus meridionalis is on average smaller than Gypaetus barbatus barbatus, lacks the face-streaks, gorget, and joined eye patches, and has 4 to 5 centimeters of the tarsi left unfeathered.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

AvesORDER

AccipitriformesFAMILY

AccipitridaeGENUS

GypaetusSPECIES

barbatusSUBSPECIES (2-13)

G. b. barbatus (Northwest African), G. b. altaicus (Himalayan), G. b. aureus (Eurasian), G. b. meridionalis (East African, South African)

Etymology

Bearded vultures are so named for the long, broad, black bristles that grow from the base of the bill that resemble a beard.

An old, common name for these birds is Lammergeier which comes from a German word meaning lamb-vulture. This name was given to bearded vultures as they were often seen carrying large animal bones and assumed to kill farmers’ livestock.

Bearded vultures are also known as Huma bird or Homa bird in Iran and northwest Asia.

A group of vultures in flight is called a kettle, while the term committee refers to a group of vultures resting on the ground or in trees. A group of vultures that are feeding is termed wake.

ALTERNATE

Huma Bird, Homa Bird, Lamb Vulture, Lammergeier, Lammergeyer, OssifrageGROUP

Committe, Kettle, Venue, Volt, WakeMALE

CockFEMALE

HenYOUNG

Chick, Hatchling

Region

The bearded vulture is widely and disjunctly distributed across the Palearctic, Afrotropical, and Indomalayan regions, but is very rare in some areas and thought to be in decline overall.

The range of bearded vultures extends across southern Europe and Asia, from as far east as the Pyrenees mountains of Spain to as far west as India and Tibet, south-central China, and southern Siberia. They can also be found across the Ethiopian highlands, as well as in northeast Uganda, west Kenya, Lesotho and southeastern South Africa. Isolated populations inhabit northern Morocco and possibly Algeria.

In India, the species is locally common throughout the Himalayas, from Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh. Some altitudinal movements occur during winter, when individuals are occasionally seen as low as 600 m. It is a widespread altitudinal migrant in Nepal, with its population in the country estimated at c.500 individuals in 2010. The species is described as rare in Bhutan. In Iraq, there may be fewer than 20 pairs, with less than 100 mature individuals in the Arabian Peninsula.

The species is regarded as rare and at high risk in Egypt. There are estimated to be a few hundred pairs in Ethiopia. In 2011, there were only three nest-sites known in Kenya, and six or more in Tanzania, with the population in Uganda unknown, although there was evidence of near total loss of the Mt Elgon population. There are estimated to be 5-10 pairs in Morocco, but not recent information on its status in Algeria, and it is considered extinct in Tunisia. In southern Africa, including South Africa, the population is estimated at c.100 breeding pairs.

In Europe, the population has grown in the Alps (with the emergence of new breeding pairs due to a reintroduction project, with 19 pairs in 2010), and in the Pyrenees, particularly in its central part (Aragon, Spain), from its population of 39 pairs in 1994 to 72 pairs in 2010. In Spain, two reintroduction projects are under way in Andalusia and the Cantabrian Mountains. The total Spanish population was estimated at 117 pairs in 2012. The total population in European Union countries was estimated at 175 pairs in 2010 and the total European population was recently estimated at 580-790 pairs. The population in Azerbaijan is estimated at 50-100 pairs and the population in European Russia is estimated at 150-250 pairs. There were thought to be 2-5 individuals in the Macedonia-Greece and Bulgaria-Greece border areas at the turn of the century, however there has been a lack of records in these areas since 2005. In Turkey, the population is estimated at around 160-200 pairs. In Armenia, the population is estimated at 15-25 breeding pairs.

In the Himalayas of India, there has been a perceived decline in recent years. It was once commonly seen in the western and central Himalayas, but in recent years it has not been observed as frequently in the central lower Himalaya, perhaps owing to disturbance, and there has been an apparent decline in Uttarakhand since the late 1990s. Populations in Ladakh and along the high Himalayas are regarded as likely to be secure. Steep declines have been recorded in the Upper Mustang region of Nepal recently, with numbers recorded per day and per kilometer decreasing by 73% and 80% respectively between 2002 and 2008. The population appears to be stable in south-eastern Kazakhstan. In Yemen, the species appears to have declined since the early 1980s. The species range and population in Turkey also appear to have declined in recent years. In Armenia, the population has been stable since the 1990s. In southern Africa, the species breeding range has declined by about 27% since the early 1980s, with the number of breeding territories declining by 32-51% between 1960-1999 and 2000-2012.

EXTANT (RESIDENT)

Afghanistan, Algeria, Andorra, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Lesotho, Morocco, Nepal, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Spain, Sudan, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, YemenEXTANT (BREEDING)

Armenia, Bhutan, China, Georgia, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, UzbekistanEXTANT (NON-BREEDING

IsraelREINTRODUCED

Austria, Italy, SwitzerlandVAGRANT

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Djibouti, Germany, Korea, Lebanon, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Portugal, Romania, Somalia, ZimbabwePOSSIBLY EXTINCT

Albania, North MacedoniaEXTINCT

Bosnia & Herzegovina, Jordan, Liechtenstein, Montenegro, Palestine, Serbia, Syria

Habitat

Bearded vultures can be found at high elevations in rugged mountainous regions. They reside between 300 and 4,500 meters above sea level, though most frequently above 2,000 meters.

Bearded vultures often inhabit remote, desolate areas containing cliffs, crags, precipices, canyons, and gorges overlooking high alpine pastures, montane grasslands, and meadows where prey animals and their predators reside. They also reside on lightly or even heavily forested slopes, steep-sided large rocky desert valleys, and high-lying steppes.

Inhabiting such an area gives scavenging bearded vultures potential access to the remains of hunted-down prey such as ibex, mountain goat, and wild sheep from major predators like wolves and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos).

SHRUBLAND

Mediterranean-Type Shrubby VegetationGRASSLAND

Temperate, Subtropical/Tropical High AltitudeROCKY AREAS

Inland Cliffs, Mountain PeaksARTIFICIAL/TERRESTRIAL

Urban Areas

Co-Habitants

Golden Eagle

Grey Wolf

Behavior

Bearded vultures are diurnal and often can be seen performing aerial displays such as mutual circling and high-speed chases. They roll over one another, displaying their talons and diving nearly completely to the ground. They also perform sky dances, ascending to high altitudes and rapidly diving down, twisting and rolling past the nesting site. These aerial displays and chases are used to communicate territory boundaries and to defend or attract mates. It is hypothesized that young birds performing these chases and dives might be engaging in social play to practice courtship skills. Practicing these skills as a juvenile may also be important in defending nests from heterospecifics when they reach maturity.

Bearded vultures perch obliquely or horizontally, looking characteristically hunch-shouldered. They normally perch openly on rock or crag, but rarely rest on tree branches.

Like all birds, bearded vultures perceive their environments through visual, tactile, auditory, and chemical stimuli.

Bearded vultures are considered Old World vultures, and like other vultures of this group, have a poorly developed sense of smell. These birds rely heavily on excellent eyesight to locate carcasses.

Bearded vultures are rarely vocal birds and remain generally silent, except in display. However, during mating, they often make loud chuckling and rather shrill, somewhat peevish whistles and noises. During courtship displays, bearded vultures are reported to emit a sharp, guttural koolik, koolik, as well as twittering shrill-like noises.

Bearded vultures are very territorial and have extremely large, vast home territories that range from 250 to 700 square kilometers. Foraging areas of have been reported to be as large as 7,500 square kilometers.

Bearded vultures are resident where they occur, but juveniles will wander more widely than adults.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

DiurnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Non-Migrant

Diet

Bearded vultures are strictly carnivorous but have a unique diet consisting mainly of bones and carrion, with bones making up 85% of their diet.

Like many other vultures they are scavengers, preying on the carcasses of dead animals. Once they locate a carcass, bearded vultures often wait for other meat-eating scavengers to pick the bones clean before feeding. They are generally unwilling to compete with other vultures at carcasses and will wait patiently at a cliff edge to feed, scavenging older carcasses if fresh meat is scarce. As a result, they often feed on older carcasses and offal, clearing even the least desirable remains other scavengers would not eat. Bearded vultures are also known to scavenge in rubbish dumps, especially in urban areas in Ethiopia.

Bearded vultures prefer the fatty anatomical parts of an animal carcass, regardless of bone length, although bone morphology as a consequence of handling efficiency or the ingestion process may also play a secondary role in food selection. These fatty bones have a higher percentage of oleic acid than non-fatty bones. The close association between the bones selected and their high fat value implies an optimization of foraging time and of the increased energy gained from the food. This is in line with selective foraging to redress specific nutritional imbalances.

Deceased mammals account for 93% of the bearded vulture’s diet, with 61% being medium-sized ungulates. They often trap larger ungulates near the edges of cliffs and force them to fall off by the vigorous beating of their wings.

Bearded vultures are also known to prey on tortoises, various species of small birds, and smaller mammal prey, such as marmots, hyraxes, and hares.

Bearded vultures look for access to the remains of hunted-down prey such as Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica), Nubian ibex (Capra nubiana), alpine ibex (Capra ibex), Walia ibex (Capra walie), wild goat (Capra aegagrus) and Iberian wild goat (Capra pyrenaica), mountain goat, and wild sheep from major predators like wolves and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos).

Bearded vultures have an extremely high acid content within their stomachs that allows them to digest bones within a 24-hour period. Bones up to 10 centimeters in diameter and weighing up to 4 kilograms can be consumed. Bones are either consumed whole, broken using the bill, hammered against the ground, or dropped onto hard rock.

When a bone is too large for a bearded vulture to consume wholly, the bird will lift the bone within its talons, lift it up 50-150 meters in the air, and carry it over to rocky bone-dropping sites, called ossuaries. Here, they are dropped repeatedly until they break open and bone marrow can be consumed.

Bearded vultures use similar techniques to kill tortoises, small birds, and smaller mammal prey such as marmots, hyraxes, and hares.

Unlike other vultures, bearded vultures deliver prey remains to their young without regurgitation. As adults, bearded vultures prefer to feed on bones, but as chicks, an important part of their diet consists of meat and skin.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Forager

Prey

Reproduction

When breeding in the wild, males are an average of 8.9 years old, while females are about 7.7 years old.

The breeding period of bearded vultures occurs from October until July and is divided into three periods: pre-laying, incubation, and chick-rearing. Breeding occurs from December to September in Europe and northern Africa; October–May in Ethiopia; May-January in southern Africa; year-round in much of eastern Africa; and December-June in India.

There is a large variation in the first flight time of chicks, though most leave at about 4 months after birth, at which point they permanently leave the nest.

Most bearded vultures are monogamous and heterosexual, but male-male mounting has been recorded within polyandrous trios in the Pyrenees mountain range of Spain and France. Unpaired or free-floating males will often join a pre-existing male and female pair, creating a trio.

Bearded vulture homosexual behavior is not directly correlated with different forms of intrasexual competition such as sperm competition or hierarchical dominance, but the formation of polyandrous trios has led to intrasexual competition between males. These intrasexual aggressions lower the frequency of heterosexual copulations during the fertile period. It also increases population densities, which may be responsible for delayed maturity in wild bearded vultures. As there is no correlation between dominance and mounting behavior. Male bearded vultures in polyandrous trios most likely mount one another to regulate levels of aggression.

Female bearded vultures in polyandrous trios prefer to mate with alpha males, but will also mate with beta males. Mating with a larger number of males may benefit the female by providing her with more parental care for her young. Extra-pair copulations may be a way to increase the likelihood of successful nesting if the first male is infertile, or may increase genetic diversity within the brood. Females may also mate with both males to avoid harassment or aggression. Reverse mounting is also common among polyandrous trios. After the alpha male drives off the beta male, he is mounted by the female.

Pairs of bearded vultures engage in copulations between 50 and 90 days before egg laying. Males tend to copulate with females more frequently in the evening after foraging for prey or bones. This may be a form of sperm competition, with individual males fighting to be the last to copulate with a female.

During mating, bearded vultures often make loud chuckling and rather shrill, somewhat peevish whistles and noises. During courtship displays, bearded vultures are reported to emit a sharp, guttural koolik, koolik, as well as twittering shrill-like noises.

Nest building starts about 111 days before egg-laying. Egg laying to fledgling lasts about 177 days. Incubation lasts approximately 54 days, starting when the first egg has been laid.

Breeding pairs of bearded vultures have several nests within a single territory, and rotate between them on a yearly basis. Males tend to more actively build nests and defend territories, while females allocate more time and energy tending to the nest. However, both males and females display territorial behavior around the nest against other bearded vultures and heterospecifics. Bearded vultures will construct large nests, averaging 1-meter in diameter, composed of branches and lined with animal remains such as skin and wool, as well as dung and occasionally also rubbish. Nests are located on remote overhung cliff ledges or in caves and will be re-used over the years.

Breaded vultures defend their nests from conspecifics primarily during the pre-laying period of the breeding season. This may be due to intrasexual competition between males or food competition. During this period, males attack invaders and use aerial attacks to defend their nests from competitors more frequently than females. This may be so females do not expend excess energy to have more available for mating. Females may also be able to assess the quality and breeding potential of a male through his ability to defend his territory and build a nest.

Breeding success of the bearded vulture may be influenced by interactions between heterospecifics. The technique of feeding and conspicuous nesting sites of bearded vultures make chicks vulnerable to kleptoparasitism. Because bearded vultures store their food in a visible and predictable manner in nests, perching sites, and ossuaries, they have aggressive interactions with common ravens (Corvus corax), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus), and other bearded vultures attempting to attack the nest in order to steal food. Aggressive interactions between bearded vultures and these species are common in nesting sectors shared by the species. Bearded vultures must actively defend their nests from this kleptoparasitism, resulting in a negative energy cost and less energy to dedicate to young. Relocating nests to avoid attacks could lead to nesting at altitudes or locations with poor weather conditions, or in closer proximity to humans.

Female bearded vultures lay one to three eggs per breeding cycle, with usually only one egg surviving. In the Pyrenean population, there is extremely low breeding productivity with only an average of 0.4 fledglings per pair per year. Mean hatching asynchrony between eggs in bearded vultures is estimated to be six days, longer than in any other raptor.

Bearded vulture chicks are born semi-altricial and require post-hatching incubation and feeding. Both parents participate in feeding and rearing their chick.

The first chick is usually larger, more active, has a more erect posture, and can call more insistently than the second chick. Parental favoritism towards the first chick is common among bearded vultures, and parents may only feed the first born. The second chick often dies very quickly, and is frequently fed to the first chick for nourishment. The poor ability of the second chick to fend for itself may be an adaptation to a quick death if the first chick survives. At the same time, the second egg may act as insurance in case the first does not survive.

Unlike other vultures, bearded vultures deliver prey remains to their young without regurgitation. As adults, bearded vultures prefer to feed on bones, but as chicks, an important part of their diet consists of meat and skin.

Juvenile bearded vultures have a much different physical appearance than adults and appear dark all over. These birds possess a dark gray-brown coloration, with a slightly lighter gray-brown abdomen and a dark brown to black colored head and neck. That have a dark-mottled buff patch on the mantle and pale tips to median wing-coverts. The crown and cheeks are paler and more buff-brown, while the upperparts are all thinly buff-streaked Due to this dark coloration, the shorter beard of juvenile bearded vultures is much less conspicuous.

BREEDING SEASON

Year-RoundPARENTAL INVESTMENT

Maternal, PaternalINCUBATION

54 DaysCLUTCH

1-3FLEDGLING

177 DaysINDEPENDENCE

###SEXUAL MATURITY

7-8 Years

Ecology

As feeders on carrion, bearded vultures dispose of rotting remains and help keep the ecosystem clear of disease. They will wait patiently at a cliff edge until other scavengers have finished eating, and will not compete for food. As a result, they often feed on older carcasses and offal, clearing even the least desirable remains other scavengers would not eat.

There are no adverse effects of bearded vultures on humans, but they continue to be persecuted for assumptions.

Unfortunately, as bearded vultures were often seen carrying large animal bones, they were assumed to kill farmers’ livestock. Many birds have been, and continue to be, persecuted for this assumption despite their scavenging habits.

SPORT HUNTING/SPECIMEN COLLECTING

Local, NationalMEDICINE

LocalPETS/DISPLAY ANIMALS, HORITCULTURE

InternationalFOOD

Local

Predators

Human

Conservation

Bearded vultures are considered Vulnerable in Europe, however, because of the extremely large range of these birds, their global evaluation is listed as Near Threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

Population

Bearded vulture population trends vary regionally and locally.

Population densities of bearded vultures are very low, as they can occupy massive ranges.

In all three of the continents that they reside in, Africa, Asia, and Europe, the range of bearded vultures has decreased tremendously, particularly in Europe. The bearded vulture population is declining throughout its range, with the exception of northern Spain, where the population has increased since 1986. Overall, it is suspected that the population has declined by 25-29% over the past three generations. Within Europe, the population is estimated to be decreasing by at least 10% in 53.4 years, or three generations.

Bearded vultures are considered Vulnerable in Europe, with less than 150 territories remaining in the European Union in 2007, and are currently being reintroduced in the Pyrenees and the Alps. The overall population of bearded vultures is estimated to number 1,300-6,700 individuals, but in Europe the population is estimated at 580-790 pairs, which equates to 1,200-1,600 mature individuals.

MATURE INDIVIDUALS

1,300-6,700FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

The main causes of on-going bearded vulture declines appear to be non-target poisoning, direct persecution, habitat degradation, disturbance of breeding birds, inadequate food availability, changes in livestock-rearing practices, and collisions with powerlines and wind turbines.

Despite the provision of targeted conservation actions, the European population remains susceptible to poisoning and mortality caused by powerlines. Since European reintroductions began, mortality from shooting has decreased, however poisoning of bait sets for carnivores, both intentional and accidental, has increased. Rapid increases in grazing pressure and human populations in the mountains of Turkey are causing habitat degradation there. Suitable habitat is also threatened by pipeline construction through the Caucasus mountains. Three of five failed eggs of this species and four dead nestlings sampled in the Spanish Pyrenees from 2005-2008 had high concentrations of multiple veterinary drugs (especially fluoroquinolones) and evidence of several livestock pathogens.

In South Asia, the most significant potential threat may be from diclofenac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used in livestock and responsible for catastrophic declines in three of the region’s Gyps species since the 1990s, through ingestion at contaminated carcasses and resultant kidney failure. The bearded vulture is primarily a bone-eater, and it is not known if diclofenac residues remain within bones of treated animals, although residues are known to be passed into feathers and hair. However, the local collapse in Gyps species could allow this species to access and feed on soft tissues from which it would have been excluded.

RESIDENTIAL & COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Housing & Urban AreasAGRICULTURE & AQUACULTURE

Annual & Perennial Non-Timber Crops, Livestock Farming & RanchingENERGY PRODUCTION & MINING

Renewable EnergyTRANSPORTATION & SERVICE CORRIDORS

Roads & Railroads, Utility & Service LinesBIOLOGICAL RESOURCE USE

Hunting & Trapping Terrestrial AnimalsINVASIVE & OTHER PROBLEMATIC SPECIES, GENES, & DISEASES

Invasive & Non-Native/Alien Species/DiseasesPOLLUTION

Agricultural & Forestry EffluentsCLIMATE CHANGES & SEVERE WEATHER

Habitat Shifting & Alteration

ACTIONS

The production of a multi-species action plan for the conservation of Africa-Eurasian vultures is underway.

In Europe, captive breeding and reintroduction programs have been carried out in the Austrian, French, Italian, and Swiss Alps with individuals subsequently spreading into other parts of France. Reintroduction programs are underway in parts of Spain. Feeding stations have been provided in the Pyrenees with resulting increases in numbers of the species, and the provision of similar stations across the species’ range could improve its global population density. However, while these have helped to increase population growth and individual survival, they can have negative impacts on vultures. For instance, they can lead to habitat saturation, with individuals’ territories overlapping at these areas and can lead to reduced productivity.

A reintroduction program was attempted in Kenya in 1999-2003. The species is monitored in Southern Africa with an annual count day which not only aids in the monitoring of the species, but also raises awareness.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Antor, R. J., Margalida, A., Frey, H., Heredia, R., Lorente, L., & Sese, J. A. (2007). First breeding age in captive and wild bearded vultures Gypaetus barbatus. Acta Ornithologica, 42(1), 114-118.

- Bertran, J. & Margalida, A. (1999). Copulatory Behavior of the bearded vulture. The Condor, 101(1), 164-168.

- (2004). Interactive behaviour between bearded vultures Gypaetus barbatus and common ravens Corvus corax in the nesting sites: Predation risk and kleptoparasitism. Ardeola, 51(2), 269-274.

- (2006, June). Reverse mounting and copulation behavior in polyandrous bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) trios. Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 118(2), 254-256.

- Bertran, J., Margalida, A., & Arroyo, B. (2009, April 15). Agonistic behaviour and sexual conflict in atypical reproductive groups: The case of bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus polyandrous trios. Ethology, 115(5), 429-438.

- BirdLife International. (2015). European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Blumstein, D. T. (1990). An observation of social play in bearded vultures. The Condor, 92(3), 779-781.

- Brown, C. J. (2003). Population dynamics of the bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus in southern Africa. African Journal of Ecology, 35(1), 53–63.

- Ferguson-Lees, J. & Christie, D. A. (2001). Raptors of the World. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Fernand, Deroussen. (April 23, 2013). XC144936 [Audio File]. Xeno-Canto.

- Margalida, A. (2008, January). Bearded vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) prefer fatty bones. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 63(2), 187-193.

- Margalida, A. & Bertran, J. (2005, March). Territorial defence and agonistic behaviour of breeding bearded vultures Gypaetus barbatus toward conspecifics and heterospecifics. Ethology, Ecology, & Evolution, 17(1), 51-63.

- Margalida, A., Bertran, J., & Boudet, J. (2005). Assessing the diet of nestling bearded vultures: A comparison between direct observation methods. Journal of Field Ornithology, 76(1), 40-45.

- Margalida, A., Bertran, J., Boudet, J., & Heredia, R. (2004, February 19). Hatching asynchrony, sibling aggression and cannibalism in the bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus. Ibis: International Journal of Avian Science, 146(3), 386-393.

- Margalida, A., Bertran, J., & Heredia, R. (2009). Diet and food preferences of the endangered bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus: A basis for their conservation. Ibis: International Journal of Avian Science, 151(2), 235-243.

- Margalida, A., Garcia, D., Bertran, J., Heredia, R. (2003, April). Breeding biology and success of the bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus in the eastern Pyrenees. Ibis: International Journal of Avian Science, 145(2), 244-252.

- Margalida, A., Heredia, R., Razin, M., & Hernandez, M. (2008). Sources of variation in mortality of the bearded vulture Gypaetus barbatus in Europe. Bird Conservation International, 18(1), 1-10.

- Margalida, A., Sanchez-Zapata, J., Eguia, S., Arroyo, A., Hernandez, F., & Bautista, J. (2009, April 21). Assessing the diet of breeding bearded vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) in mid-20th century in Spain: A comparison to recent data and implications for conservation. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 55(4), 443-447.

- Tenenzapf, J. (2011). “Gypaetus barbatus“. Animal Diversity Web (ADW).