PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

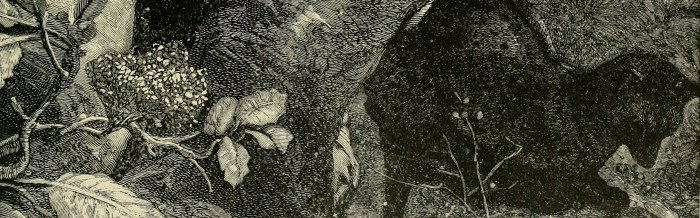

The common palm civet, also known as the Asian palm civetor toddy cat is the most common of the civet species and resides in Asia. Not much is known about this civet’s behaviors as it’s shy, nocturnal, and arboreal, leading it to hide amongst the trees at night to evade predators. With numerous subspecies categorized within this species, the common palm civet can have a multitude of different appearances and variations.t

Physiology

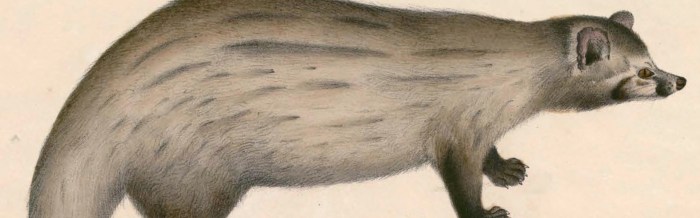

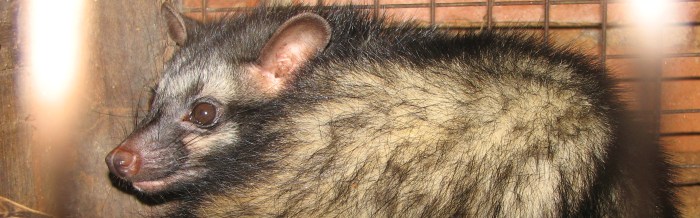

Common palm civets are small, weighing only about three kilograms with an average body length of 50 centimeters, and a tail that is 48 centimeters long. They have elongated bodies with short legs, and a tail that is almost as long as their head and body combined.

The coats of common palm civets are short, coarse, and are usually black or gray with black-tipped guard hairs all over. Like racoons, palm civet faces are banded and have a white patch of fur below and above the eyes and on each side of the nose. They can be recognized by the dark stripes down their back and the three rows of black spots freckled on each side of their body and covering their legs. However, these markings are less prominent in juveniles.

Unlike other civets, common palm civets tails do not have black rings. Rather, they are just tipped black on the very end. Another distinguishing factor is that their neck hair grows backwards, whereas other members of the civet family have forward growing neck hair.

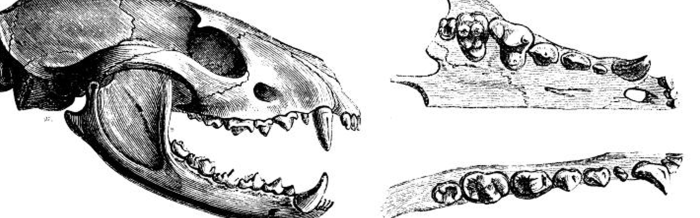

Palm civets have more specialized teeth for an omnivorous diet than other civets that mostly eat meat. Common palm civets have teeth that are weaker and pointed, and the carnassials, that are apt for slicing meat, are less developed.

The nose of the common palm civet is pointed and protrudes from its small face. They have faces mostly like cats, but palm civets have longer and flatter skulls. Relative to their head, palm civets have large dark eyes and large pointed ears.

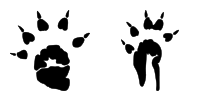

Having plantigrade feet, common palm civets walk like bears and racoons, with their entire sole on the ground. They have naked soles, their claws are semi-retractile, and their third and fourth toes are partly fused. All these features make them excellent climbers and help them as they hunt.

Both males and females of the common palm civet have a perineal scent gland under their tail, resembling testicles. This gland is located within a double-pocket pouch under the skin of the abdomen, and is used to spray in defense, to mark territory, and for communication with others of the species.

Common palm civets typically live anywhere from 15 to 20 years. They live longer in captivity, living for as long as 24 years and 5 months.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

NoneBODY HEIGHT

38 cm. / 15 in.BODY LENGTH

43-71 cm. / 17-28 in.TAIL LENGTH

48 cm. / 19 in.BODY MASS

1-5 kg. / 4-11 lb.DENTAL FORMULA

I ³⁄3, C ¹⁄1, P ³⁄₄, M ¹⁄2, ×2 = 40LIFESPAN

15-25 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

7.7 yr.LOCOMOTION

Plantigrade

Images

Taxonomy

Viverra hermaphrodita was the original scientific name proposed for the common palm civet by Peter Simon Pallas in 1777. It is the nominate subspecies and ranges in Sri Lanka and southern India as far north as the Narbada River. Several zoological specimens were described between 1820 and 1992.

The common palm civet is currently recognized under the name Paradoxurus hermaphroditus.

The common palm civet is one of three species comprising the palm civet genus Paradoxurus that was denominated and first described by Frédéric Cuvier in 1822, along with the brown palm civet (Paradoxurus jerdoni) and the golden palm civet (Paradoxurus zeylonensis). This genus is within the viverrid family of Viverridae containing 14 genus and 33 species.

Many subspecies of the common palm civet have been described, notably the taxon lignicolor, described by Miller in 1903 and endemic to the Mentawai islands. This has a debated taxonomic status, being sometimes considered a separate species or as a subspecies of P. hermaphroditus. The taxonomic status of these subspecies has not yet been evaluated.

As this account was being finalised, it was proposed that P. hermaphroditus contains at least three species: P. hermaphroditus, the Asian palm civet found in southern China and non-Sundaic Southeast Asia, P. musanga, the Southeast Asian palm civet from Sumatra, Java, and other small Indonesian islands, and P. philippinensis, the Philippine palm civet originating from the Mentawai Islands, Borneo, and the Philippines. P. musanga was originally described as P. musangus by Raffles in 1821 and P. philippinensis was first described by Jourdan in 1837.

It was suspected that in the region of overlap between P. hermaphroditus and P. musanga they would be found to be separated by altitude. The morphological distinctiveness of the Mentawai taxon was confirmed; although placed as a subspecies within P. musanga, it was cautioned that further investigation might find species rank more appropriate; genetic data do not, as so far looked at, support species status.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

MammaliaORDER

CarnivoraFAMILY

ViverridaeGENUS

ParadoxurusSPECIES

hermaphroditusSUBSPECIES (34)

P. h. hermaphroditus (Indian), P. h. balicus (Bali), P. h. bondar (Bengal/Nepal), P. h. canescens, P. h. cantor, P. h. canus, P. h. cochinensis, P. h. dongfangensis, P. h. enganus, P. h. exitus, P. h. hanieli, P. h. javanica (Javan), P. h. kangeanus, P. h. laotum (Myanmar/Thailand), P. h. laneus, P. h. lignicolor (Mentawai Islands), P. h. milleri, P. h. minor (Indochinese), P. h. musanga (Southeast Asian), P. h. nictitans (Odisha), P. h. pallasii (Assam/Myanmar/Nepal/Sikkim), P. h. pallens, P. h. parvus, P. h. philippinensis (Bornean & Philippine), P. h. pugnax, P. h. pulcher, P. h. sacer, P. h. scindiae (Central Indian), P. h. senex, P. h. setosus, P. h. siberu, P. h. simplex, P. h. sumbanus, P. h. vellerosus (Kashmir)

Etymology

Common palm civets are known by many names, such as Asian palm civets, toddy cats, musang, weasel cats, luwak, and several others. Their name varies based on the behavior of the civets and the region in which they are found.

Both males and females of the common palm civet have a perineal scent gland under their tail, resembling testicles; the feature that gave them their scientific name, Paradoxurus hermaphroditus.

The common palm civet feeds from fig trees and palm trees, hence the origin of one of its common names, the palm civet.

ALTERNATE

Asian Palm Civet, Mentawai Palm Civet, Lusaka, Musang, Musang Lusaka, Musang Pulitzer, Onion Thief, Palm Cat, Palm Civet, Paradoxurus, Toddy Cat, Tree Cat, Tree Dog, Weasel Cat, Wood-Dog

Region

The common palm civet has a wide distribution in South and South-East Asia from Afghanistan in the west to Hainan and the adjacent Chinese coast in the east. It occurs widely on South-East Asian islands, but the natural pattern of occurrence there is uncertain, given the evidence of introduction by people.

Animals in Sulawesi and the Lesser Sundas eastwards appear to be introductions, while the Philippine archipelago might have been colonised naturally but also might stem entirely from introductions.

Its recorded distribution in China is restricted to Hainan, southern Guangdong, (perhaps based on a trade animal,) south-western Guangxi, much of Yunnan, and south-western Sichuan provinces. It occurs on the small islands of Bawean, Indonesia; Con Son, Viet Nam; Koh Samui, Thailand; Koh Yao, Thailand; and Telebon, Thailand, and on the Philippine islands of Balabac, Busuanga, Camiguin, Culion, Leyte, Luzon, Marinduque, Mindanao, Negros, Palawan, Sangasanga, Sibuyan (specimens) and Catanduanes, Biliran, Maripipi, and Panay (other indications.)

It is sometimes stated to have been introduced to Japan, but this reflects confusion with Masked Palm Civet Paguma larvata.

EXTANT

Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei, Darussalam, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, VietnamINTRODUCED

IndonesiaUNCERTAIN

Papua New Guinea

Habitat

Where common palm civets choose to live depends mostly on the availability of food and presence of areas they can rest in, like tree hollows, rock crevices, or dense foliage.

Common palm civets can live in a variety of habitats. They naturally live in temperate and tropical forests, but in developed areas they are also found in parks, suburban gardens, plantations, and fruit orchards.

Although adapted for forest living, this civet tolerates living in areas near people: commuting along wires and pipes, sleeping in barns, drains, or roofs during the day; and coming out at night to catch rats or forage.

Common palm civets use a wide range of habitats including evergreen and deciduous primary and secondary forests, seasonally flooded Melaleuca-dominated peat swamp forests, Bangladesh Sundarbans mangroves, monoculture plantations, such as oil palm and teak, villages, and even urban environments. They naturally live in temperate and tropical forests, but in developed areas they are also found in parks, suburban gardens, plantations, and fruit orchards.

FOREST

Subtropical/Tropical Dry, Subtropical/Tropical Moist Lowland, Subtropical/Tropical Mangrove Vegetation Above High Tide Level, Subtropical/Tropical Swamp, Subtropical/Tropical Moist MontaneSHRUBLAND

Subtropical/Tropical Dry, Subtropical/Tropical Moist, Subtropical/Tropical High AltitudeGRASSLAND

Subtropical/Tropical Dry, Subtropical/Tropical Seasonally Wet/Flooded, Subtropical/Tropical High AltitudeARTIFICIAL/TERRESTRIAL

Arable Land, Pastureland, Plantations, Rural Gardens, Urban Areas, Subtropical/Tropical Heavily Degraded Former Forest

Co-Habitants

Behavior

Even though common palm civets are one of the most common species of civets, it is one of the least studied mammals. It is often among the most commonly photographed small carnivores by ground-level camera-traps, yet little is known about its behavior due to their nocturnal, quiet, and secretive nature.

Common palm civets are arboreal so they spend most of their time in fruit trees and fig trees, preferring the tallest trees with very dense canopies and vines for seclusion and protection. Their elevation range extends up to about 2,000 feet.

The common palm civet’s arboreal and nocturnal characteristics are thought to have developed as a mechanism to avoid predators.

Common palm civets rarely communicate vocally other than when they are agitated or being attacked. Civets are typically silent, but can make a noise that sounds similar to meows. They also snarl, hiss, moan, whine, cough, call, and spit when they are alarmed or harassed.

Common palm civets generally rely on scent-markings and olfactory responses to communicate, instead of using vocalizations. Scent glands are used as their primary means of communication. Common palm civets are able to secrete self-identifying odors from their perineal gland, urine, feces, and skin glands. They mark their ranges by dragging their anal glands on the ground and predominately mark substrates by dragging their perineal gland on top of them. Scents left from the dragging the perineal gland remain in the environment longer than any other scent Asian palm civets produce and are used as a long-term source of information about that animal. They also rub their ear-neck region and heels.

Male common palm civets mark objects with their scent a lot more frequently than females of the species. This is probably because males are more territorial and dominant than females.

Generally, Asian palm civets remain in forested areas during the majority of their life in a typical area ranging from 1.4 to 50 square kilometers. Throughout the night, they travel several hundred meters, with a mean distance of 215 meters, mostly in the search of food. Several studies on the range and movement habits of Asian palm civets have used radio-tracking collars. They found that males have much larger ranges than females, at 17 square kilometers and 2 square kilometers, respectively.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

NocturnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Non-Migrant

Diet

Common palm civets are opportunistic and adaptable, eating whatever is available; however, they are mostly frugivorous, preferring berries and pulpy fruits over anything else. They are particularly fond of chiku, mangoes, bananas, rambutan, pineapples, melons, and papayas.

Palm civets of Java are said to feed on over 35 different species of trees, shrubs, and creepers. Common palm civets eat the seeds of many trees in their area, like palm trees (Pinanga kuhlii and Pinanga zavana).

Other than fruits, common palm civet are very fond of the sap from the flowers of sugar palm trees (Arenga pinnata) that are found throughout their natural range. They also drink the nectar of silk cotton trees (Ceiba petandra) and the stems of the apocynaceae tree.

Since Asian palm civets are foragers, they are frequently found in urban gardens, plantations, and orchards looking for food. In addition to their normal diet of fruit, civets also eat rats, shrews, mice, birds, insects, worms, seeds, eggs, reptiles, snails, scorpions, coffee, insects, molluscs, and more.

Common palm civets climb fruit trees to get their food. Their favorite trees to feed from are fig trees and palm trees, hence the origin of one of its common names, the palm civet. They are particularly fond of chiku, mangoes, bananas, rambutan, pineapples, melons, and papayas.

Palm civets are noted for their ability to pick the best and ripest fruit, leaving the others for later.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Forager

Reproduction

Common palm civets are elusive, so their reproductive behavior has mostly been observed in a zoo setting and their mating system is unknown.

Common palm civets find mates using scent markings from their anal glands, indicating each civet’s age, sex, receptivity, kin relationship, and if they are familiar.

Asian palm civets go into resting trees to mate, give birth, and take care of young, spending the whole mating period in their tree of choice. Couples tend to choose trees for this period in close proximity to other members of their group.

Common palm civets are classified as altricial, meaning the young need care from their parents after birth. Little is known about parental investment in Asian palm civets since the young do not leave the tree hollows that they are born in until after they are weaned. However, it is thought that females are responsible for care of the young, providing milk for nourishment from their mammary glands, as well as being in charge of weaning them.

BREEDING SEASON

Year-RoundESTROUS CYCLE

82 DaysPARENTAL INVESTMENT

MaternalGESTATION

60 DaysLITTER

2-5WEANING

2 MonthsINDEPENDENCE

3 MonthsSEXUAL MATURITY

9-12 Months

Ecology

Common palm civets are sometimes compared to northern raccoons (Procyon lotor) from North America, in that they fill a similar niche. They are opportunistic and adaptable, eating whatever is available.

Common palm civets eat the seeds of many trees in their area, like palm trees (Pinanga kuhlii and Pinanga zavana). They are prime contributors to the dispersal of these seeds, since they tend to pass them in their feces several hundred meters from where the seeds were consumed. This also encourages the seeds to germinate, which helps forests regenerate.

Common palm civets are most commonly hunted by large cats, like tigers (Panthera tigris) and leopards (Panthera pardus), and reptiles, like large snakes and crocodiles.

Common palm civet is a large part of the general mammal harvest for eating in South-East Asia, both for subsistence but also for trade to urban luxury restaurants. Common palm civet is hunted, often a part of general take, using non-selective methods, for wild meat in some parts of its range, such as southern China, parts of North-East India, especially in Nagaland and hilly areas of Manipur, Lao, Vietnam, Thailand, and probably throughout northern South-East Asia and widely elsewhere in its range.

Dead individuals of this species were found with local tribes during a visit to Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, and Agra, Uttar Pradesh in India between 1998 and 2003, where it is killed for its meat. Hunting in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, India, has apparently much declined and this is probably typical for India excepting the North-East.

One of the earliest uses that humans have used common palm civets for was their sweet-smelling musk. In the past, it was used to treat such things as scabies, but today it is only used for perfume. To get civet oil, the scent gland must be scraped out with a special tool, which is a difficult task and, if not done, properly is painful for the civet. The musk can also be produced when the civet is harassed. Often, this industry is supported by trappers that go into the wild and capture wild civets to obtain their oil.

Common palm civets are best known for aiding in the production of an expensive coffee, Kopi luwak, by passing coffee cherries through their digestive tract. As the cherries go through palm civets digestive tracts, they get a unique “gamy” flavor and people extract these pits from the civet feces. This coffee is in high demand because of civets tendencies to only pick the ripest coffee cherries. Kopi luwak is the most expensive coffee in the world, selling for over one hundred dollars a pound.

There has been a recent great increase in numbers of Asian palm civets kept captive for the production of civet coffee, especially in Indonesia and, to a lesser extent, in the Philippines.

The most common problem that common palm civets cause humans is raiding of plantations and orchards for their fruits. Owners of these lands retaliate by killing them and persecuting them as pests. Also, civets that live in roofs or in barns make a lot of noises at night, making people think of them as a nuisance. Even so, Asian palm civets seem able to tolerate very high levels of persecution.

FOOD

Local, NationalPETS/DISPLAY ANIMALS, HORTICULTURE

National, InternationalOTHER

National, International

Conservation

The common palm civet is listed as Least Concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species because it has a wide distribution, large populations, uses a broad range of habitats and is tolerant of extensive habitat degradation and change, and is evidently resilient to ‘background’ hunting levels. These attributes mean that it is unlikely to be declining at the rate required to qualify for listing even as Near Threatened.

With a recent upsurge in off-take over a significant part of its range, this categorization warrants review when better data on the effects of this off-take become available.

Population

Across its wide range, the common palm civet is often one of the most commonly recorded species of civets and small carnivores. It is the most common mammalian carnivore on Palawan Island in the Philippines and is often among the most commonly photographed small carnivores by ground-level camera-traps.

Across its range it has been found commonly in degraded and anthropogenic habitats, with some records from even the most degraded small isolates amid human environments, such as Houay Nhang in Lao PDR and Hlawga in Myanmar. In North-east India and non-Sundaic South-east Asia it is common in the remote interiors of large blocks of closed evergreen forest, whereas certainly in mainland India and perhaps in Sundaic South-east Asia it is rare in in such habitat, while still common in degraded and edge habitats.

In southern China where it is extensively hunted, the common palm civet is mostly not common, perhaps as a result of decline, but Guangxi and Guangdong also comprise the edge of its range.

The recent rapid rise in production of civet coffee, a practice using mainly this species, and a new craze for keeping this species as a pe‘ have both presumably resulted in greatly increased off-take from the wild in Indonesia. There is no meaningful information as to the effects of these recent changes. Civet coffee farms are also expanding rapidly in Vietnam.

Together with ongoing hunting pressure, particularly in northern South-east Asia, it is likely that the global population is in decline. Given the large areas with only minimal off-take, such declines are at present likely to be very shallow.

FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

Even though palm civets are not currently in danger, their habitats are getting increasingly smaller due to over-logging and clearing of land for palm oil plantations.

Some governments have started monitoring the rate of logging and requiring developers to get permits or licenses to do so. There has also been an effort to replant some of the lost forests.

BIOLOGICAL RESOURCE USE

Hunting & Trapping Terrestrial Animals

ACTIONS

The common palm civet is found within many protected areas across its range, such as in Lao, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, China, North-East India, and Java.

Common palm civets are not considered to be in danger of extinction, but are protected under law in their native areas of Malaysia, Myanmar, and Sichuan, China. They are also protected in India under the Indian Wildlife Protection Act of 2004 and in Bangladesh under the Wildlife Act of 2012. They are not protected in Thailand.

Although the common palm civet is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, they are listed as Vulnerable under China’s red list for excessive hunting. This species is listed on CITES Appendix III (India).

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Acharjyo, L. N. & Mohapatra, S. (1978). Birth and growth of common palm civet (Paradoxurus Hermaphroditus) in captivity. The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 75, 204-206.

- Asian palm civet. (2017, February, 16). A-Z Animals.

- Asian palm civet. (2017, December 3). Wiktionary.

- Asian palm civet. (2017, December 16). Wikipedia.

- Asian palm civet. Animals Adda.

- Asian palm civet. The Animal Files.

- Asian palm civet. Animal Spot.

- Azlan, J. (2003, October). The diversity and conservation of mustelids, viverrids, and herpestids in a disturbed forest in Peninsular Malaysia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 29, 8–9.

- Burton, M. (1968). University Dictionary of Mammals of the World. New York, NY: T.Y. Crowell.

- Choudhury, A. (2013, January). The Mammals of North East India. Guwahati, Assam, Indi: Gibbon Books and the Rhino Foundation for Nature in NE India.

- Chua, M. A. H., Lim, K. K. P., & Low, C. H. S. (2012, December). The diversity and status of the civets (Viverridae) of Singapore. Small Carnivore Conservation, 47, 1–10.

- Chutipong, W., Tantipisanuh, N., Ngoprasert, D., Lynam, A. J., Steinmetz, R., Jenks, K. E., Grassman Jr., L. I., Tewes, M., Kitamura, S., Baker, M. C., McShea, W., Bhumpakphan, N., Sukmasuang, R., Gale, G. A., Harich, F. K., Treydte, A. C., Cutter, P., Cutter, P. B., Suwanrat, S., Siripattaranukul, K., Hala-Bala Wildlife Research Station, Wildlife Research Division and Duckworth, J. W. (2014, December). Current distribution and conservation status of small carnivores in Thailand: A baseline review. Small Carnivore Conservation, 51, 96–136.

- Common palm civet. (2002). Blue Planet Biomes.

- Common palm civet. Animal Corner.

- Common palm civet: Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. (2016, October). WildFactSheets.

- Common palm civet: Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. Wildlife Singapore.

- Common palm civet: (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus). iNaturalist.

- Corbet, G. B. & Hill, J. E. (1992). Mammals of the Indo-Malayan Region: A Systematic Review. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Coudrat, C. N. Z., Nanthavong, C., Sayavong, S., Johnson, A., Johnston, J. B., & Robichaud, W. G. (2014, February 28). Conservation importance of Nakai-Nam Theun National Protected Area, Laos, for small carnivores based on camera trap data. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 62, 31–49.

- Duckworth, J. W. (1997, April). Small carnivores in Laos: A status review with notes on ecology, behaviour and conservation. Small Carnivore Conservation, 16, 1–21.

- Duckworth, J. W., Timmins, R. J., Choudhury, A., Chutipong, W., Willcox, D. H. A., Mudappa, D., Rahman, H., Widmann, P., Wilting, A., & Xu, W. (2016). Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41693A45217835.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. (2017, October 5). Civet. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Grassman, L. I., Jr. (1998, October). Movements and fruit selection of two Paradoxurinae species in a dry evergreen forest in Southern Thailand. Small Carnivore Conservation, 19, 25-29.

- Gray, T. N. E., Pin C., Phan C., Crouthers, R., Kamler, J. F., & Prum S. (2014, July). Camera-trap records of small carnivores from eastern Cambodia, 1999–2013. Small Carnivore Conservation, 50, 20–24.

- Gupta, B. K. (2004, October). Killing civets for meat and scent in India. Small Carnivore Conservation, 31, 21.

- Heaney, L. R., Balete, D. S., Dolar, M. L., Alcala, A. C., Dans, A. T. L., Gonzales, P. C., Ingle, N. R., Lepiten, M. V., Oliver, W. L. R., Ong, P. S., Rickart, E. A., Tabaranza, B. R., Jr., & Utzurrum, R. C. B. (1998, June 30). A synopsis of the mammalian fauna of the Philippine Islands. Fieldiana: Zoology, New Series, 88, 1–61.

- Holden, J. & Neang T. (2009, April). Small carnivore records from the Cardamom Mountains, southwestern Cambodia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 40, 16–21.

- Kakati, K. & Srikant, S. (2014, July). First camera-trap record of small-toothed palm civet Arctogalida trivirgata from India. Small Carnivore Conservation, 50, 50–53.

- Kalle, R., Ramesh, T., Sankar, K., & Qureshi, Q. (2013, December). Observations of sympatric small carnivores in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Western Ghats, India. Small Carnivore Conservation, 49, 53–59.

- Khan, M. M. H. (2008). Protected Areas of Bangladesh- A guide to Wildlife. Nishorgo Program. Bangladesh Forest Department, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Kopi Luwak / Civet Coffee. All about palm civet cats. Most-Expensive.Coffee.

- Larivière, S. (2003, November 20). Palm civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus Spanish: Musang in M. Hutchins, D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, & M. C. McDade (Eds.), Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia: Mammals III (2 ed., Vol. 14) (pp. 344). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group, Inc., division of Thomson Learning Inc.

- Lau, M. W. N., Fellowes, J. R., & Chan, B. P. L. (2010, October). Carnivores (Mammalia: Carnivora) in South China: A status review with notes on the commercial trade. Mammal Review 40(4), 247–292.

- Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. Paradoxurus hermaphroditus: (Pallas, 1777). The DNA of Singapore.

- Lopez-Terrill, V. (2017, March 31). Genus-species: Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. The Warren and Genevieve Garst Photographic Collection.

- Low, C. H. S. (2011, December). Observations of civets, linsangs, mongooses and non-lutrine mustelids from Peninsular Malaysia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 45, 8–13.

- Maddox, T., Priatna, D., Gemita, E., & Salampessy, A. (2007, October). The Conservation of Tigers and Other Wildlife in Oil Palm Plantations. Jambi Province, Sumatra, Indonesia. ZSL Conservation Report No. 7. London: The Zoological Society of London.

- Meiri, S. (2005, October). Small carnivores on small islands: New data based on old skulls. Small Carnivore Conservation, 33, 21-23.

- Mudappa, D., Noon, B. R., Kumar, A., & Chellam, R. (2007, April). Responses of small carnivores to rainforest fragmentation in the southern Western Ghats, India. Small Carnivore Conservation, 36, 18–26.

- Nakabayashi, M. Bernard, H., & Nakashima, Y. (2012, December). An observation of several Common Palm Civets Paradoxurus hermaphroditus at a fruiting tree of Endospermum diadenum in Tabin Wildlife Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia: Comparing feeding patterns of frugivorous carnivorans. Small Carnivore Conservation, 47, 42-45.

- Nakashima, Y., Nakabayashi, M., & Jumrafiha, A. S. (2013). Space use, habitat selection, and day-beds of the common palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus) in human-modified habitats in Sabah, Borneo. Journal of Mammalogy, 94(5), 1169–1178.

- National Parks Board. Civets. (2014, December 30). National Parks.

- Nelson, J. (2013). Paradoxurus hermaphroditus: Asian palm civet, Animal Diversity Web.

- Nijman, V., Spaan, D., Rode-Margono, E. J., Roberts, P. D., Wirdateti, & Nekaris, K. A. I. (2014, December). Trade in common palm civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus in Javan and Balinese markets, Indonesia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 51, 11–17.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker’s Mammals of the World (6th ed., Vol. 2). Baltimore: MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Palm civet. (2012). In Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged, (10th ed.). HarperCollins Publishers.(2014). In Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, (12th ed.). HarperCollins Publishers.

- Palm civet. (2016). In American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

- Palm civet. (2018). In The Random House Dictionary. Random House, Inc.

- Palm civet. In Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. (2014, November 22). Wikimedia Commons.

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus: Common palm civet. Taxo4254.

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus. Zipcode Zoo.

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus: Asian palm civet. Encyclopedia of Life (EOL).

- Paradoxurus hermaphroditus (Pallas, 1777). Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

- Patou, M. L., Wilting, A., Gaubert, P., Esselstyn, J. A., Cruaud, C., Jennings, A. P., Fickel, J., & Veron, G. (2010, November). Evolutionary history of the Paradoxurus palm civets – A new model for Asian biogeography. Journal of Biogeography, 37(11), 2077–2097.

- Rabinowitz, A. R., (1991, February). Behaviour and movements of sympatric civet species in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand. Journal of Zoology, 223(2), 281-298.

- Roberton, S. I. (2007). Status and Conservation of Small Carnivores in Vietnam (Doctoral dissertation). University of East Anglia, Norwich, U.K.

- Rode-Margono, E. J., Voskamp, A., Spaan, D., Lehtinen, J. K., Roberts, P. D., Nijman, V., & Nekaris, K. A. I. (2014, July). Records of small carnivores and of medium-sized nocturnal mammals on Java, Indonesia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 50, 1–11.

- Rozhnov, V. V., Rozhnov, V. Y. (2003). Roles of different types of excretions in mediated communication by scent marks of the common palm civet, Paradoxurus hermaphroditusPallas, 1777 (Mammalia, Carnivora). Biology Bulletin, 30(6), 584-590.

- Rozhnov, V., V. Yu. 2003. Roles of different types of excretions in mediated communication by scent marks of the common palm civet, Paradoxurus hermaphroditus Pallas, 1777 (Mammalia, Carnivora). Biology Bulletin, 30/6: 584-590. Rozhnov, V., V. Yu. 2003. Roles of different types of excretions in mediated communication by scent marks of the common palm civet, Rozhnov, V., V. Yu. 2003. Roles of different types of excretions in mediated communication by scent marks of the common palm civet, Paradoxurus hermaphroditus Pallas, 1777 (Mammalia, Carnivora). Biology Bulletin, 30/6: 584-590. , 30/6: 584-590. Samejima, H. & Semiadi, G. (2012, June). First record of Hose’s Civet Diplogale hosei from Indonesia, and records of other carnivores in the Schwaner Mountains, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 46, 1–7.

- Schreiber, A., Wirth, R., Riffel, M., & Van Rompaey, H. (1989). Weasels, Civets, Mongooses, and Their Relatives. An Action Plan for the Conservation of Mustelids and Viverrids. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

- Shepherd, C. R. (2012, December). Observations of small carnivores in Jakarta wildlife markets, Indonesia, with notes on trade in Javan Ferret Badger Melogale orientalis and on the increasing demand for Common Palm Civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus for civet coffee production. Small Carnivore Conservation, 47, 38–41.

- Spaan, D., Williams, M., Wirdateti, Semiadi, G., & Nekaris, K. A. I. (2014). Use of raised plastic water-pipes by common palm civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus for habitat connectivity in an anthropogenic environment in West Java, Indonesia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 51, 85–87.

- Stevens, K., Dehgan, A., Karlstetter, M., Rawan, F., Tawhid, M. I., Ostrowski, S., Ali, J. M., & Ali, R. (2011). Large mammals surviving conflict in the eastern forests of Afghanistan. Oryx, 45, 265–271.

- Su, S. (2005, October). Small carnivores and their threats in Hlawga Wildlife Park, Myanmar. Small Carnivore Conservation, 33, 6-13.

- Than Zaw, Saw Htun, Saw Htoo Tha Po, Myint Maung, Lynam, A. J., Kyaw Thinn Latt, & Duckworth, J. W. (2008, April). Status and distribution of small carnivores in Myanmar. Small Carnivore Conservation, 38, 2–28.

- Veron, G., Patou, M.-L., Toth, M., Goonatilake, M., & Jennings, A. P. (2015, May 1). How many species of Paradoxurus civets are there? New insights from India and Sri Lanka. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 53(2), 161–174.

- Wahyudi, D. & Stuebing, R. (2014). Camera trapping as a conservation tool in a mixed-use landscape in East Kalimantan. Journal of Indonesian Natural History, 1(2), 37–46.

- Wang, Y. X. (2003). A Complete Checklist of Mammal Species and Subspecies in China (A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference). Beijing, China: China Forestry Publishing House.

- Wemmer, C., J. Murtaugh. (1981). Copulatory behavior and reproduction in the binturong, Arctictus binturong. Journal of Mammalogy, 62(2), 342-352.

- Wildscreen Arkive. Common palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus). Arkive.

- Wilson, D. E. & Reeder, D. M. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3 ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Wilting, A., Samejima, H., & Mohamed, A. (2010, December). Diversity of Bornean viverrids and other small carnivores in Deramakot Forest Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia. Small Carnivore Conservation, 42, 10–13.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). Order Carnivora. In: D. E. Wilson & D. M. Reeder (Eds.), Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3 ed.)(pp. 532-628). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.