PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The great horned owl is a member of the Strigidae family, categorized within the Strigiformes order under the higher Aves class and is also known as the tiger owl or the hoot owl. It is one of the largest owl species in the world and eats a wide variety of woodland animals.

Physiology

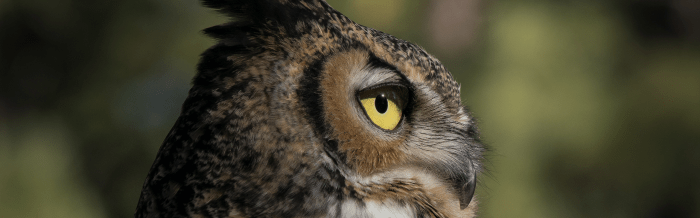

The great horned owl is not only the most formidable in appearance of all owls, but it is also the most powerful. The great grey owl (Strix nebulosa) and the snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) may appear larger, but the great horned owl exceeds them in courage, weight, and strength.

The great horned owl is the largest of the common resident owls of the United States. The great horned owl is larger than the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) with an even greater wing spread. Males measure from 45-58 centimeters, or 18-23 inches, with females slightly larger at 55-64 centimeters, or 22-25 inches.

The sex difference in great horned owls is best known. Females are much larger than males, yet they possess smaller syringes. Females weigh about 50% more than males with males weighing about 1.3-1.7 kilograms, or 3-3.8 pounds and females weighing up to 2.2 kilograms, or 4.8 pounds. Contrarily, the syringes of females average 17% smaller than those of males.

The great horned owl is generally colored for camouflage. The underparts of the species are usually light with some brown horizontal barring; the upper parts and upper wings are generally a mottled brown usually bearing heavy, complex, darker markings. All subspecies are darkly barred to some extent along the sides, as well.

A variable-sized white patch is seen on the throat. The white throat may continue as a streak running down the middle of the breast even when the birds are not displaying, which in particularly pale individuals can widen at the belly into a large white area. South American great horned owls typically have a smaller white throat patch, often unseen unless actively displaying, and rarely display the white area on the chest. Individual and regional variations in overall color occur, with birds from the subarctic showing a washed-out, light-buff color, while those from the Pacific Coast of North America, Central America, and much of South America can be a dark brownish color overlaid with blackish blotching. The skin of the feet and legs, though almost entirely obscured by feathers, is black. Even tropical great horned owls have feathered legs and feet. The feathers on the feet of the great horned owl are the second-longest known in any owl (after the snowy owl). The bill is dark gunmetal-gray, as are the talons.

All great horned owls have a facial disc. This can be reddish, brown, or gray in color (depending on geographical and racial variation) and is demarked by a dark rim culminating in bold, blackish side brackets.

The great horned owl’s tufts, or plumicorns, are not the owl’s ears, but rather clumps of feathers found on the heads of some owls and not on others. There are several suggestions as to the purpose of the great horned owl’s tufts, but the function is unknown. The theory that they serve as a visual cue in territorial and sociosexual interactions with other owls is generally accepted. Theories include for camouflage, which makes the owl look like a branch on a tree from a distance; to help owls to distinguish each other from other species in low-light conditions; to make owls look fiercer to predators or nest intruders; and to help owls to communicate. If an owl is alert and watchful, its ear tufts will go up, but if it’s scared or angry, its ear tufts will go down.

In the great horned owl, the extensor (fused) tendons of the leg, which retract the toes and clinch the claws, pass through a groove in the tarso-metatarsus and then into and through a hole in the bone, such as how a rope passes through a pulley-block. The tendons are thus held firmly in place as they pass over and through what would be the heel in a human being. When the leg is bent and drawn up, the tendons are also drawn tight, clenching the toes and driving in the talons.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

Larger, Heavier Females with Smaller SyringesSHOULDER HEIGHT

45-64 cm. / 18-25 in.WINGSPAN

188-152 cm. / 35-60 in.BODY MASS

1-3 kg. / 3-6 lb.LIFESPAN

13-28 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

10.6 yr.LOCOMOTION

Digitigrade

Images

Taxonomy

The great horned owl is part of the genus Bubo, which may include as many as 25 other extant species, predominantly distributed throughout Africa.The great horned owl represents one of the one or two radiations of this genus across the Bering land bridge to the Americas. Whereas the Magellanic horned owl (Bubo magellanicus) clearly divided once the owl had spread through the Americas, the consensus seems to be that the snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) and the great horned owl divided back in Eurasia and the snowy then spread back over the Arctic throughout northernmost North America separately from the radiation of the horned owl.

Pleistocene era fossils have been found of Bubo owls in North America, which may either be distinct species or paleosubspecies, from as far east as Georgia, but predominantly in the Rocky Mountains and to the west of them. Almost all fossils indicate these owls were larger than modern great horned owls.

The great horned owl and it closely related species, the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo), may in fact be conspecifics, based on similarities in life history, geographic distribution, and appearance. As such, the great horned owl is often compared to the eagle-owl, though the eagle-owl is larger and occupies the same ecological niche in Eurasia. In one case, a zoo-kept male great horned owl and female Eurasian eagle-owl produced an apparently healthy hybrid.

Genetic testing indicates that the snowy owl, not the Eurasian eagle-owl, is the great horned owl’s most closely related living species.

The great horned owl is also often compared to the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) because they share similar habitat, prey, and nesting habits, but the hawk is more diurnal.

A large number of great horned owl subspecies, more than 20 altogether, have been named. However, many of these are not true races and only examples of individual or clinal variation. Subspecies differences are mainly in color and size and generally follow Gloger’s and Bergmann’s rules: The most conservative treatments of great horned owl races may describe as few as 10 subspecies, although an intermediate number is typical in most writings.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

AvesORDER

StrigiformesFAMILY

StrigidaeGENUS

BuboSPECIES

virginianusSUBSPECIES (15)

B. v. virginianus (Common, Eastern), B. v. algistus (St. Michael), B. v. deserti (Bahia) B. v. elachistus (Baja California, Dwarf), B. v. heterocnemis (Labrador, Newfoundland, Northeastern, Snyder’s), B. v. lagophonus (Northwestern), B. v. mayensis (Yucatán), B. v. mesembrinus (Central American, Oaxaca), B. v. nacurutu (South American, Venezuelan), B. v. nigrescens (Colombian, Ecuadorian, North Andean), B. v. pacificus (California, Coastal), B. v. pallescens (Desert, Southwestern, Virginia), B. v. pinorum (Rocky Mountains), B. v. saturates (Coastal, Northwestern, St. Michael), B. v. subarcticus (Arctic, Northern, Pale, Subarctic, Western, White)

Etymology

The great horned owl is also known as the tiger owl or hoot owl. Tiger owl was originally derived from early naturalists’ description of the bird as the winged tiger or tiger of the air.

The word owl originated in early European languages. In old Norse, anowl was known as ugla, and in old German, it was uwila. Both of these words may have been created as sounds that described the unique call of an owl. Other ancient cultures also had words for owl that described the owl’s hooting call – In India, Owls were once known as oo-loo and in Hebrew, o-ah.

In Old English, about 600 A.D. to about 1000 A.D., owl was ule, a word similar to the original Dutch word. In Middle English, about 1000 A.D. to the 1400s, the word became owle, later shortened to the form we use today. Throughout this time, various early written records have variations on this spelling, including uwile, oule, owell, hoole, and howyell.

ALTERNATE

Big Hoot Owl, Cat Owl, Chicken Owl, King Owl, Tiger of the Air, Tiger Owl, Winged TigerGROUP

Parliament, StareMALE

CockFEMALE

HenYOUNG

Chick, Owlet, Fledgling

Region

The great horned owl is common and widely distributed. Since the division into two species, the great horned owl is the second most widely distributed owl in the Americas, just after the common barn-owl, but its ability to colonize islands is apparently considerably less than those of common barn-owls (Tyto alba) and short-eared owls (Asio flammeus)

The great horned owl can be found throughout the timbered regions of North, Central, and South America, from the Arctic regions in the North, to the Straits of Magellan in the South. This bird is distributed throughout most of North American and very spottily in Central America and then down into South America south to upland regions of Argentina, Bolivia and Peru, before they give way to the Magellanic horned owl (Bubo magellanicus), which thence ranges all the way to Tierra del Fuego, the southern tip of the continent. More specifically, the owl is found in south central and southeastern Canada and east central and eastern United States, from southern Ontario and southern Quebec south to the Gulf coast and Florida and west to Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota, Iowa, southeastern South Dakota, eastern Nebraska, eastern Kansas, Oklahoma and eastern and southern Texas.

Great horned owls are extant breeding residents in Argentina, Belize, Boligiva, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The breeding habitat of the great horned owl extends high into the subarctic of North America, where they are found up to the northwestern and southern Mackenzie Mountains, Keewatin, Ontario, northern Manitoba, Fort Chimo in Ungava, Okak, Newfoundland and Labrador, Anticosti Island and Prince Edward Island.

In Central America and the mangrove forests of northwestern South America, the great horned owl is absent or rare from southern Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. There have only been two records of great horned owls in Panama. The species is also absent from the West Indies, the Queen Charlotte Islands, and almost all off-shore islands in the Americas.

Great horned owls are extant, but non-breeding in Saint Pierre and Miquelon and are extant and vagrant in Bermuda, the Falkland Islands, Panama, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

EXTANT

Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, Suriname, United States, Uruguay, VenezuelaVAGRANT

Bermuda, Falkland Islands, Panama, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

Habitat

Great horned owls are well suited for many habitats and environments. and are among the world’s most adaptable owls, or even bird species, in terms of habitat.

Great horned owls are most commonly found in interspersed areas of woodland and open fields. Their habitats include forest, savanna, shrubland, rocky areas, deserts, swamps, marshes, mangroves, and both rural and urban human settlements.

The great horned owl can take up residence in trees that border all manner of deciduous, coniferous, and mixed forests, tropical rainforests, pampas, prairie, mountainous areas, deserts, subarctic tundra, rocky coasts, mangrove swamp forests, and some urban areas. It is less common in the more extreme areas of the Americas. In the Mojave and Sonora Deserts, they are absent from the heart of the deserts and are only found on the vegetated or rocky fringes. Even in North America, they are rare in landscapes including more than 70% old-growth forest, such as the aspen forest of the Rockies. They have only been recorded a handful of times in true rainforests such as the Amazon rainforest. In the Appalachian Mountains, they appear to use old-growth forest, but in Arkansas are actually often found near temporary agricultural openings in the midst of large areas of woodland. Similarly in south-central Pennsylvania, the owls uses cropland and pasture more than deciduous and total forest cover, indicating preference for fragmented landscapes. In prairies, grasslands and deserts, they can successfully live year around as long as there are rocky canyon, steep gullies and/or wooded coulees with shade-giving trees to provide them shelter and nesting sites.

These owls live at a variety of elevations, from sea level up to 4,000 meters.

FOREST

Boreal, Temperate, Subtropical/Tropical Dry, Subtropical/Tropical Moist Lowland, Subtropical/Tropical Mangrove Vegetation Above High Tide Level, Subtropical/Tropical Swamp, Subtropical/Tropical, Moist MontaneSAVANNA

Dry, MoistSHRUBLAND

Subtropical/Tropical Dry, Subtropical/Tropical High AltitudeROCKY AREAS

Inland Cliffs, Mountain Peaks DESERT TemperateARTIFICIAL/TERRESTRIAL

Arable Land, Urban Areas

Co-Habitants

Ruffed Grouse

Yellow-Billed Magpie

House Mouse

Bald Eagle

American Crow

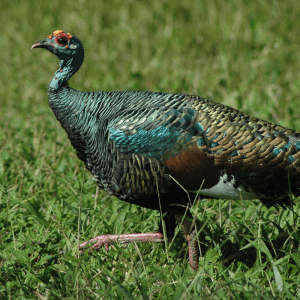

Ocellated Turkey

Goldfish

Virginia Opossum

Red-Tailed Hawk

Barred Owl

Blue Jay

Wild Turkey

Mule Deer

American Badger

Coyote

Black-Billed Magpie

American Beaver

Barn Swallow

Red Fox

Northern Cardinal

Mourning Dove

Behavior

The silent flight of the great horned owl is powerful, swift, skillful, and graceful. When leaving a perch, the great horned owl flaps its great wings heavily and rapidly, with its feet dangling. The feet are soon drawn up into the plumage and the wings spread, as it glides swiftly away for a long period of sailing on fixed wings. It threads its way with perfect precision through the branches of the forest trees, or glides at low levels over the open meadows, where it can drop swiftly and silently on its unsuspecting prey.

Any white moving object is likely to attract the attention of the great horned owl and bring on an attack. A great horned owl was known to have struck the claws of both feet into the back of a large collie dog (Canis lupus familiaris), perhaps misled by a white patch on the dog as the white on the back of a skunk, its favorite mark. Another struck the head of a man who was riding on horseback at night through a large tract of woods while wearing a white American beaver (Castor canadensis) hat. The noiseless blow delivered such force that it took the man’s hat and scared the man to flee at top speed for about three miles. Yet another instance happened in the autumn of 1918 when a man wearing a white canvas hat stepped out behind his cabin in the Wareham woods for a little gymnastic exercise and a great horned owl almost brushed his ear, probably spotting the moving hat in the moonlight from the top of some tall pine and shooting over the cabin roof before realizing his mistake just in time.

Great horned owls are assessed as “full migrants” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). In winter, great horned owls often leave regions where suitable food is scarce. Probably, there is some migration of these birds every year from the northern parts of their range toward more southern regions. In some seasons of scarcity, this migration increases to considerable proportions. The spring migration northward is not so evident as the fall exodus. They are not always successful in this migratory search, however, and now and then, one is found starved and frozen in the snow. Such specimens, when discovered, are very much emaciated.

When the great horned owl settles down on a limb, its toes and talons lock round it and hold the bird firmly, allowing it to sleep.

The ability of great horned owls to revolve their heads through 180° is frequently used to advantage. Hearing is also exceedingly acute in great horned owls. The owls take a very active interest in their surroundings and even the slightest sounds attract their attention at once. It is almost impossible to surprise a great horned owl, even when approach is made as cautiously as possible and from the side where no glimpse of the observer could be obtained. Not only is it possible for them to hear the slightest sound, but they can readily localize it. Experiments were made where the observer, concealed, gave various sounds and each time the direction was detected.

Great horned owl calls are divided into three main categories: hoots, chitters, and squawks. Great horned owl calls can be further subdivided into five types of hoots, four types of chitters, and five types of squawks based on inflection, number of syllables, duration, pitch, volume, and behavioral context. Two types of non-vocal communication are also distinguished: hisses and bill clacking.

One function of a great horned owl’s hooting is its challenge to others of his sex. In regions where great horned owls are common, the males do a great deal of competitive hooting from favorite perches in their territories. Thus, in the creek bottoms south of Lawrence, Kansas, where one horned owl territory was often hemmed in on two sides by the ranges of other individuals, one bird would hoot and in regular sequence as many as four or five others would answer. It was seldom that two birds were heard calling simultaneously.

At times the male great horned owl appears to hoot for the mere pleasure of hearing his own voice. The notes produced by great horned owls are an indescribable assemblage of hoots, chuckles, screeches, and squawks given so rapidly and disconnectedly that the effect is both startling and amusing. Judging from its effect upon other owls of the species and the circumstances under which it is given, hooting of the male has a three-fold function. As with the songs of birds in general, hooting seems to be an expression of physical vigor and vitality. Such language is often heard when several birds gather together during the mating season and indulge in vocal battles. On rare occasions similar outbursts are heard at other seasons of the year.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

Diurnal, NocturnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Full Migrant

Diet

The great horned owl is carnivorous and feeds on small mammals, such as mice and rats and birds.

In eating its prey, this owl usually begins at the head and eats backward. Prey birds are plucked, but small mammals are swallowed whole, head first.

The great horned owl’s favorite part of its prey to eat is the brains. Ordinarily, when there is good hunting, the great horned owl has a plentiful supply of food, and when there is game enough, it slaughters an abundance and eats only the brains.

The great horned owl’s speed, weight, and muscular power all combine to give the bird the force to overcome animals many times its own weight. The arrangement of the great horned owl’s tendons and their connection with the machinery of the toes form a powerful equipment with which to strike its prey. When the bird strikes a victim, the force of the blow alone tends to bend the legs, contract the tendons, and drive the claws into a vital part. In addition to this, the powerful muscles of the legs are brought into play to force the talons home. Indeed, the great horned owl little regards the size of its victim for it strikes down geese and turkeys many times its weight, and has even been said at times to drive the bald eagle (Haliaeetus Leucocephalus) away.

The great horned owl, like some other birds of prey, often has a regular feeding roost, to which it brings its prey to be torn up and devoured. This may be an old, unoccupied nest, a wide, flat branch of a tree, the hollowed top of a stump, or a hollow place on a fallen log. They are usually not far from the nesting sites. Such places are profusely decorated with the remains of the feasts, feathers, bones, fur, pellets, and droppings.

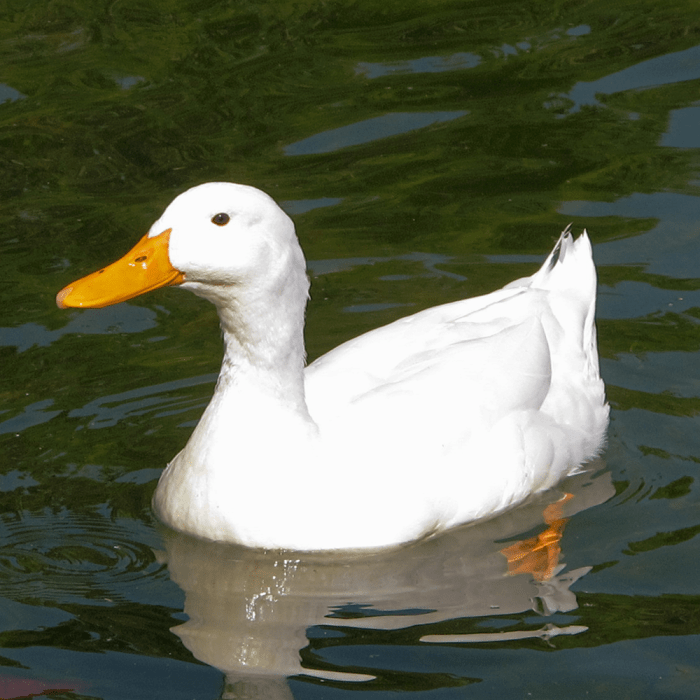

The great horned owl kills weaker owls from the barred owl (Strix varia) down, most of the hawks, and such nocturnal animals as weasels and minks. Game birds of all kinds, (grouse, turkeys, rails, quails, pheasants) wading birds, (geese, phalaropes, woodcocks, wild ducks,) poultry, (domesticated ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus), chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus), guinea hens) a few small birds (woodpeckers), rabbits, (especially bush rabbits,) hares, squirrels, gophers, mice, rats, woodchucks, opossums, porcupines, skunks, snakes, fish, (dace, goldfish (Carassius auratus), bullheads, perch,) eels, crawfish, scorpions, frogs, and insects (crickets, beetles, grasshoppers, katydids,) are all eaten by this rapacious bird. It is particularly destructive to rats.

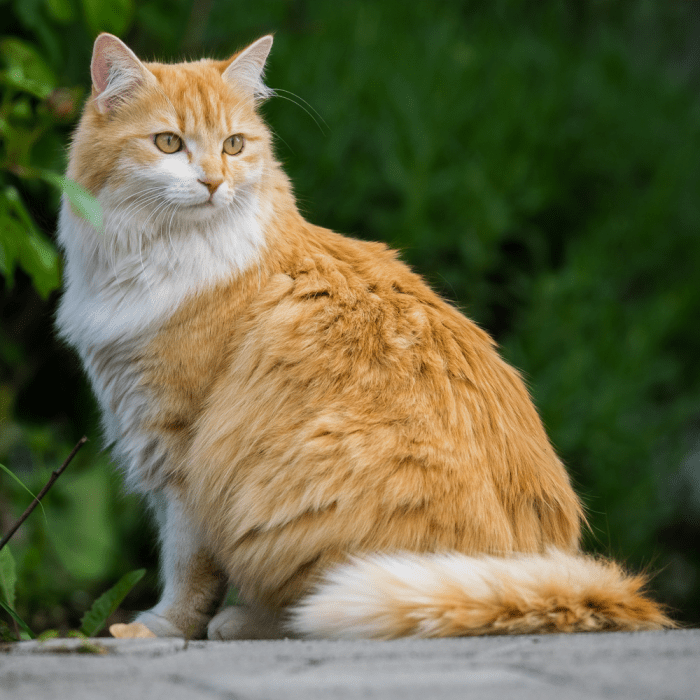

Ordinarily, when there is good hunting, this owl has a plentiful supply of food, and when there is game enough, it slaughters an abundance and eats only the brains; but in winter when house mice (Mus musculus) keep mostly within the buildings, when woodchucks and skunks have holed up, and when field mice are protected by deep snow, then if rabbits are scarce and starvation is imminent, the owl will attack even the domestic cat (Felis catus), and usually with success.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Ambush

Prey

Barred Owl

Goldfish

Cat

Domestic Duck

House Mouse

Chicken

Reproduction

The most important function of great horned owl hooting is to attract a mate. During the great horned owl mating season, the challenging, deep, rich tones of the males are occasionally interspersed with the higher and huskier notes of the females. The hoots of female horned owls are not usually identified at any time except the mating and nesting period and there is doubt if they do much calling at other seasons. Even at that season they do not seem as vociferous as the males. The latter may call back and forth at regular intervals for hours at a time, while the female owl’s calling periods, at short and indefinite time intervals, seldom exceed more than fifteen to twenty minutes.

Of the North American species, great horned owls are one of the first to nest in the spring. Great horned owl eggs have been taken as early as late November and early December in Florida. In Texas, they lay in January and early February. As one moves northward, a direct correlation between latitude and date of laying can be observed, until the extreme is reached in Labrador where sets are often not completed until after the first of April. In the western part of the country the correlation with latitude is often obscured by the effect of altitude upon climatic conditions.

Great horned owls nest in almost every type of situation in which birds nest, a range of variation unequalled by any other North American bird. From numerous records, it is apparent that the choice of nesting sites of the great horned owls throughout their wide range includes almost every type of situation in which birds nest, a range of variation unequaled by any other North American bird. From extreme heights of almost a hundred feet to American badger (Taxidea taxus) and coyote (Canis latrans) dens in the ground, the situations include old nests of other birds and even squirrels, hollow trees and stumps, holes and ledges on cliffs, hay barns, prehistoric ruins, cathedral towers, and even the open ground. Throughout the timbered regions of eastern North America, the birds have been most frequently recorded to occupy old nests of crows, hawks, ospreys, bald eagles (Haliaeetus Leucocephalus), herons, and squirrels. In one case, the owl laid its eggs in a cavity in the side of an eagle’s nest and both families occupied the same habitation. Most of these situations are from twenty to seventy feet from the ground and located near the edge of fairly dense timber. Hollows in trees or limbs are often reported, especially in the southern states, and in more hilly country ledges on cliffs are not uncommonly described. In western North America where small caves or niches in cliffs and mountain slopes are available, tree sites are often passed up for these more inaccessible situations. Old black-billed magpie (Pica hudsonia) nests are particularly favored in the Northwest. In treeless regions such as the Prairie Provinces of Canada and the Great Plains of western United States low cliffs, buttes, railroad cuts, and even low bushes appear just as satisfactory as more elevated sites. Ground nests are occasionally reported here and appear to be more common than in other parts of this bird’s range. In the deserts of the Southwest cactus plants take the place of trees and horned owls often occupy old nests among the thorny branches.

From an examination of their nests, it is evident that great horned owls clear out a certain amount of debris before the eggs are laid, and usually line it with a more or less complete layer of consisting of shreds of bark, leaves, or down plucked from the breast feathers of the incubating bird. Feathers from their prey may be added at times. Near Indian Head, Saskatchewan, the birds occasionally build rabbit fur into their nests before the eggs are laid. The extent of the lining of downy feathers varies considerably with individual birds from a few feathers to a fluffy mass which practically encloses the large eggs. On the bare floor of a hollow tree or cavity in a cliff the eggs are often enclosed merely by a rim of sticks, stones, or bits of rubbish. A nest of Bubo virginianus pallescem in Mexico was described as composed entirely of regurgitated pellets.

There may be a direct correlation between the number of great horned owl eggs and the abundance of food. The usual number of eggs for the great horned owl is two. Along the Atlantic seaboard this number is most frequently recorded, with three eggs uncommonly found and sets of four very rare. In Florida one egg often constitutes a full set. In central and western North America the sets appear to be definitely larger, with three and four eggs not uncommon, and five and six occasionally reported. This may be due to the more abundant food supply. Pacific horned owls tend to lay larger sets of eggs during wet than dry seasons, potentially because the birds find food more plentiful at such times.

There is a low percentage of infertility in great horned owl eggs. There are records of great horned owl egg sets that were partially or completely infertile but in most cases all of the eggs hatch.

Great horned owls have been known to act as if wounded as a protest against intruders to their nests with young. The great horned owl will flutter over the ground like a ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) uttering short “wailing” notes and beating the ground with one wing and then the other to act as if wounded as a protest against intruders to their nests with young.

NESTING SEASON

November-AprilBROOD

2-4PARENTAL INVESTMENT

Maternal, PaternalINCUBATION

30-37 DaysCLUTCH

1-6FLEDGLING

6-9 WeeksINDEPENDENCE

5-10 WeeksSEXUAL MATURITY

1-3 Years

Ecology

In the wilderness, the great horned owl exerts a restraining influence on both the game and the enemies of the game, for it destroys both and thus does not disturb the balance of nature. On the farm or the game preserve, however, the bird is not tolerated.

Great horned owls are at the top of many food chains and are not preyed upon by other species. However, territorial disputes between members of the same species can be fatal. Sometimes, American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) or raccoons (Procyon lotor) eat their eggs, however.

The great horned owl is the most deadly enemy of the American crow, taking old and young from their nests at night and killing many at their winter roosts. Blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) are a close second enemy, followed by all other small birds. Great horned owls tend to attract clamors of noisy, excited mobs of crows. If an owl is discovered by a crow, the alarm is immediately given and all the crows within hearing respond to the call, gather about the owl flying around or perching in the tree as near to the owl as they dare go, cawing loudly and making a great fuss. They are seldom bold enough to strike the owl.

Great horned owls have yet to be tamed and seldom make satisfactory pets. Despite their dignified bearing and handsome plumage, great horned owls do not make pleasing additions to aviaries as they are the most irredeemably morose and untamable. Even when raised in captivity, the animals often remain surly, sullen, morose, vicious, and hostile, often flying in rage at strangers and even their owners.

Certain native tribes regarded the great horned owl as the very personification of the Evil One. They feared the great horned owl’s influence and regarded its visits to their dwellings as portentous of disaster or death. This fowl is the most morose, savage, saturnine, and untamable of all New England birds.

PETS/DISPLAY ANIMALS, HORTICULTURE

InternationalSPORT HUNTING/SPECIMEN COLLECTING

Local, National

Predators

American Crow

Northern Raccoon

Human

Conservation

The great horned owl is listed as Least Concern on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species because of its extremely large range, stable population, and extremely large population size.

The great horned owl has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence <20,000 km2 combined with a declining or fluctuating range size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of locations or severe fragmentation). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern.

Population

The great horned owl’s population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over ten years or three generations). The population size is extremely large, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population size criterion (10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure).

FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

Great horned owls are one of the most widespread and successful bird species in the United States. They are not threatened or endangered.

ACTIONS

There are no action recovery plans in place for the great horned owl, but there is a systematic monitoring scheme.

Conservation sites have been identified over the great horned owl’s entire range and the species occurs in at least one protected area. There is no invasive species control or prevention.

Individuals of this species have not been successfully reintroduced or introduced benignly and the species is not subject to ex-situ conservation.

The great horned owl is not subject to recent education and awareness programs and is not included in international legislation. It is, however, subject to international management and trade controls.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Artuso, C., Houston, C. S., Smith, D. G., & Rohner, C. (2013). Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), version 2.0. In P. G. Rodewald (Ed.), The Birds of North America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Baumgartner, F. (1983). Courtship and nesting of the great horned owls. The Wilson Bulletin, 50(4), 274-285.

- Bendire, C. (1892). Bubo virginianus (Gmelin). In Life histories of North American birds with special reference to their breeding habits and eggs, with twelve lithographic plates (Vol. 1). (pp. 376-380). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Bent, A. C. (1937). Bubo virginianus (Gmelin). In Life histories of North American birds of prey in two parts (Vol. 2) (pp. 295-322). New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

- BirdLife International. (2016). Bubo virginianus, Great Horned Owl. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Braekevelt, C. (1993). Fine structure of the pecten oculi in the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). Histol Histopath, 8(1), 9-15.

- Brewster, W. (1925). Birds of the Lake Umbagog region of Maine. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 42(2), 453.

- Broley, C. L. (1947). Migration of bald eagles. The Wilson Bulletin, 59.

- Brown, R., Baumel, J., & Klemm, R. (1994). Anatomy of the propatagium: The great horned owl. Journal of Morphology, 219(2), 205-224.

- Bubo virginianus. ZipcodeZoo.

- Bubo virginianus (Gmelin, 1788). Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

- Bubo virginianus: Great Horned Owl. Encyclopedia of Life (EOL).

- Cornell University. (2013, September). A teacher’s guide to owls. 1-8.

- Dietrich, D. 2013. Bubo virginianus: Great horned owl. Animal Diversity Web (ADW).

- Dixon, J. B. (1914, March/April). History of a pair of Pacific horned owls. Condor, 16(2), 47-54.

- DLTK’s Inc. Great horned owl. Kidzone.

- Errington, P. L. (1932). Studies on the behavior of the great horned owl. The Wilson Bulletin, 44, 212-220.

- Explore Annenberg LLC. Livecams: Great horned owl. Explore.

- Forbush, E. H. (1929). Bubo virginianus virginianus (Gmelin). Great Horned Owl. In Birds of Massachusetts and other New England states (Vol. 2) (pp. 219-228). Norwood Massachusetts: Norwood Press.

- Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). The Internet Bird Collection.

- Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). iNaturalist.

- Holt, D. W., Berkley, R., Deppe, C., Enríquez Rocha, P., Petersen, J. L., Rangel Salazar, J. L., Segars, K. P., Wood, K. L. & Marks, J. S. (2017). Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E. (Eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

- Huey, L. M. (1935). February bird life of Punta Penascosa, Mexico. The Auk, 52, 249-256.

- Jacobs, J. W. (1908, June). Bald Eagle (Haliætus leucocephalus.) and Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) Occupying the Same Nest. The Wilson Bulletin, 20(2), 103-104.

- Kaufman, K. Great horned owl: Bubo virginianus. National Audubon Society.

- Kinstler, K. (2009). Great horned owl Bubo virginianus vocalizations and associated behaviours. Ardea, 97(4), 413-420.

- Lepage, D. Great horned owl: Bubo virginianus (Gmelin, JF, 1788). Avibase.

- Miller, A. H. (1934). The vocal apparatus of some North American owls. Condor, 36, 204-213.

- Porter, C. AV#11643 [Audio file]. AVoCet.

- Rasmussen, P. C. (2012, April 29).#AV16113 [Audio file]. AVoCet.

- Reed, B. P. (1925). Growth development and reactions of young great horned owls. The Auk, 42(2), 14-31.

- Rockwell, R. B. (1909, May/June). The use of magpies’ nests by other birds. Condor, 11(3), 90-92.