PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The African wild dog is Africa’s second most endangered carnivore. Its name derives from its painterly, colorful pelt markings that are unique to each dog. As a social species, these dogs live in packs up to 40, led by an alpha male and female. Group hunts are led in daylight and prey is quickly eaten alive.

Physiology

African wild dogs have large, rounded, distinctive ears; a slim, lean body; and long, muscular, slender legs with four toes on each foot. They have a digitigrade locomotion style.

African wild dogs differ from other members of the Canidae family in build, ear size, number of toes, dentition, skull size, and fur.

The African wild dog is the bulkiest and most solidly built of African canids. By body mass, they are only outsized amongst other extant canids by the grey wolf species complex (Canis lupus). However, compared to members of the genus Canis, the African wild dog is comparatively lean and tall, with outsized ears.

African wild dogs only have four toes on each paw instead of five, as they lack the dew claws of other canids. The middle two toepads are usually fused.

African wild dogs have degeneration of the last lower molar, narrow canines, and proportionately larger premolars, which are the largest relative to body size of any carnivore other than hyenas. They have around 42 teeth, including premolars, that are much larger to consume vast amounts of bone. The heel of the lower carnassial M1 is crested with a single, blade-like cusp, which enhances the shearing capacity of the teeth, thus the speed at which prey can be consumed. This feature, termed trenchant heel, is shared with two other canids: the dhole (Cuon alpinus) and the bush dog (Speothos venaticus). The skull is relatively shorter and broader than those of other canids.

The fur of the African wild dog differs significantly from that of other canids, consisting entirely of stiff bristle-hairs with no underfur. The African wild dog’s uniquely patterned fur appears to be irregularly painted with brown, caramel, red, black, yellow, and white areas. The mottled fur is short, with little or no underfur, and the blackish skin is sometimes visible where fur is sparse. Typically, there is dark fur on the head and a white tip on the end of their bushy tail. Their muzzles are black with a black line extending down the forehead.

Each African wild dog has a uniquely patterned coat, different from any other dog, much like the stripes of zebras, the spots of a giraffe, or the fingerprints of a human.

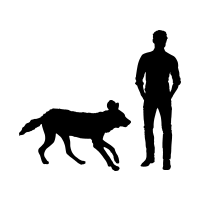

African wild dogs are about the same size as a German shepherd domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris). Males and females tend to be approximately the same size, but sometimes males are 3-7% larger than females. East and West African wild dogs tend to be smaller than those in South Africa. The body length is between 75 and 110 centimeters (29-43 inches), the tail is between 30 and 40 centimeters long (11-16 inches), and they range in weight from 18 to 36 kilograms (39-79 pounds).

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

NoneSHOULDER HEIGHT

75 cm. / 2.4 ft.BODY LENGTH

75-110 cm. / 2.4-3.6 ft.TAIL LENGTH

30-40 cm. / 11-16 in.BODY MASS

18-37 kg. / 39-80 lb.DENTAL FORMULA

I ³⁄3, C ¹⁄1, P ⁴⁄₄, M ²⁄3, ×2 = 42LIFESPAN

10-13 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

5 yr.LOCOMOTION

Digitigrade

Images

Taxonomy

Despite their name, African wild dogs are not taxonomically wild dogs.Though African wild dogs are a member of the Canidae family, which also includes dogs, coyotes, dingos, jackals, and wolves, they last shared a common ancestor with wolves about 6 million years ago. They are the only species in the genus Lycaon, which is more closely related to wolves than domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris).

In contrast, domestic dogs derived from the grey wolf (Canis lupus) within the last 30,000 years. In fact, chimpanzees and gorillas are closer to humans than wolves are to African wild dogs. Everything from the phylogeny, evolutionary development, and behavior suggests that African wild dogs are more closely related to wolves than to dogs. Although the wild dog may be about the size of a German shepherd and may look similar to some dogs, they don’t bark and have different teeth and toes. African wild dogs have four toes on each foot, lacking the dew claw that most domestic dogs have. African Wild Dogs only have four toes on each paw instead of five, as they lack the dew claws of other canids. The wild dogs also have around 42 teeth, including premolars, that are much larger than in other canids. These larger teeth allow the dogs to consume large amounts of bone.

Lastly, although many have tried, African wild dogs have never been domesticated.

African wild dogs are also commonly mistaken for spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta), although hyenas are most closely related to cats and are categorized in the Feliformia suborder, rather than the Caniformia suborder of the African wild dog.

As of 2005, five subspecies of African wild dogs are generally recognized. Nevertheless, although the species is genetically diverse, these subspecific designations are not universally accepted. East African and Southern African populations were once thought to be genetically distinct, based on a small number of samples, but more recent studies with a larger number of samples showed that extensive intermixing has occurred between the East African and Southern African populations in the past. Some unique nuclear and mitochondrial alleles are found in Southern African and Northeastern African populations, with a transition zone encompassing Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Southeastern Tanzania between the two. The West African population may possess a unique haplotype, thus possibly constituting a truly distinct subspecies.

The Cape wild dog (L. p. pictus) is the nominate subspecies and was described by Coenraad Temminck in 1820. This subspecies inhabits the Cape area of Southern Africa and are characterized by a large amount of yellow-orange fur overlapping the black. They also have partially yellow backs of the ears, mostly yellow underparts, and a number of whitish hairs on the throat mane. Those in Mozambique are distinguished by the almost equal development of yellow and black on both the upper- and underparts of the body, as well as having less white fur than the Cape form.

The East African wild dog (L. p. lupinus) was described by Thomas in 1902 and resides in East Africa, as the name would imply. This subspecies is distinguished by a smaller size and a high-contrast coat. The black markings are very dark, and although there are few yellow markings, they are a bright yellow-orange.

A few years later, in 1904, Thomas described another subspecies, the Somali wild dog (L. p. somalicus). The subspecies resides in the Horn of Africa and is similar to the East African wild dog but is smaller with shorter, coarser fur and weaker dentition. Its color closely matches the Cape wild dog, with the yellow markings being more buff rather than bright orange.

Another several years later, in 1907, Thomas with Wroughton described the Chad wild dog (L. p. sharicus) that inhabited Chad.

Lastly, the West African wild dog (L. p. manguensis) was described by Matschie in 1915 and resides in Central and West Africa. This subspecies is generally smaller than those that reside in South Africa.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

MammaliaORDER

CarnivoraFAMILY

CanidaeGENUS

LycaonSPECIES

pictusSUBSPECIES (5)

L. p. pictus (Cape), L. p. lupinus (East), L. p. manguensis (West), L. p. sharicus (Chad), L. p. somalicus (Somali)

Etymology

The African wild dog is known by several different common names including hunting dog, hyena dog, painted wolf, and ornate wolf. In Swahili, the African wild dog is known as Mbwa mwilu.

The African wild dog’s scientific name, Lycaon pictus, reflects the color of its spotted pelage. Lycaon comes from the Greek language for wolf and pictus is derived from Latin, meaning paintedor ornate.

Unfortunately, the name African wild dog has had several negative connotations that have been detrimental to the endangered species’ image and conservational efforts. As such, some conservationalists have begun using the name painted wolf to re-brand the African wild dog and make the animal sound exotic, rather than feral. Some argue that this shift may help promote positive attention and combat frequent misconception that African wild dogs are just feral dogs. This strategy has worked for other animals, such as the re-brand from killer whale to orca for Orcinus orca.

ALTERNATE

African Hunting Dog, African Painted Dog, African Painted Wolf, Cape Hunting Dog, Hyena Dog, Ornate Wolf, Painted Hunting DogGROUP

PackYOUNG

Pup

Region

Historical data indicates that African wild dogs were formerly distributed throughout sub-Saharan Africa, from desert to mountain summits, and probably were absent only from lowland rainforest and the driest desert. At one time the distribution of the African wild dog was throughout the non-forested and non-desert areas of Africa.

African wild dogs have disappeared from much of their former range and their current distribution is more fragmented. African wild dogs are now found in Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, parts of Zimbabwe, Swaziland, and the Transvaal. The species is virtually eradicated from North and West Africa and greatly reduced in Central Africa and North-east Africa. The largest populations remain in southern Africa (especially northern Botswana, western Zimbabwe, eastern Namibia, and western Zambia) and the southern part of East Africa (especially Tanzania and northern Mozambique).

African wild dogs show morphological and genetic variation in different parts of their geographic range. These regions are geographical separated by areas of unoccupied range and/or major geographical barriers, and with no expectation of recovering connectivity.

EXTANT

Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Senegal, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Zambia, ZimbabwePOSSIBLY EXTINCT

Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Nigeria, Togo, UgandaEXTINCT

Burundi, Cameroon, Egypt, Eritrea, Eswatini, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Mauritania, Rwanda, Sierra LeonePRESENCE UNCERTAIN

Algeria, Guinea

Habitat

African wild dogs occupy a range of habitats including forest, savanna, shrubland, grassland, and even desert. They prefer habitats with abundant prey, a permanent water source, and a low concentration of lions (Panthera leo) and spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta).

While early studies in the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania, led to a belief that African wild dogs were primarily an open plains species and resided in short-grass plains and bushy savannas, more recent data indicate that they reach their highest densities in thicker bush, such as in the Selous Game Reserve of Tanzania, Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe, and northern Botswana.

Several relict populations occupy dense upland forest and open woodlands, such as in the Harenna Forest in Ethiopia, but not in lowland forest or jungle areas.

African wild dogs have also been recorded in desert, although most desert populations are now extirpated. Their habitat includes semi-desert to mountainous areas south of the Sahara Desert in Africa.

It appears that the African wild dog’s current distribution is limited primarily by human activities and the availability of prey, rather than by the loss of a specific habitat type.

FOREST

Subtropical/Tropical Dry, Subtropical/Tropical Mangrove Vegetation Above High Tide Level, Moist MontaneSAVANNA

Dry, MoistSHRUBLAND

Subtropical/Tropical DryGRASSLAND

Subtropical/Tropical DryDESERT

Hot

Co-Habitants

Impala

African Buffalo

Lesser Kudu

Common Warthog

Thomson’s Gazelle

Waterbuck

Greater Kudu

Common Wildebeest

Common Duiker

Steenbok

African Elephant

Spotted Hyaena

Black Rhino

Cape Scrub Hare

Vervet Monkey

Nile Crocodile

Leopard

Lion

Common Eland

Aardvark

Behavior

Because African wild dogs use their sight, rather than smell, to find prey, they are primarily diurnal and crepuscular, hunting in the morning and early evening. They will only hunt at night if there is a bright moon.

African wild dogs are gregarious animals that form packs of up to 40 members. Before the recent population decline of African wild dogs, packs of up to 100 animals had been recorded. An average pack size, currently, is 7 to 15 members.

African wild dogs have unique social concerns and structures within their packs. Each pack has separate dominance hierarchies for males and females and has an alpha male and alpha female, which are the dominant pair.

African wild dogs are cooperative hunters and hunt in packs led by the pack’s alpha male. The African wild dog uses sight, rather than smell, to find prey, then begins to chase the animal once located. The chase can last for several kilometers and reach speeds up to 55 kilometers per hour. The dogs chase the prey until it tires, attacking on the flanks and rump to attempt to bring the animal down. At times, the dogs will disembowel the prey while it is still running. Once the prey is brought down, the dogs tear it to pieces while it’s still alive, each dog taking as much meat as possible.

African wild dogs cooperate in caring for the young, as well as wounded or sick pack members. When the dogs return from a kill they feed regurgitated food to the young, wounded, and sick, as well as any adult that was not able to go on the hunt.

Another unique feature of African wild dogs is the general lack of aggression between pack members. An exception to this is the occasional fight between a dominant female and a subordinate female over breeding rights.

Female African wild dogs have a much higher rate of emigration from their natal group than do males. Females usually leave the pack at 2.5 years or older to join other packs that have no adult females. Approximately half of young males will stay with their father’s pack, the rest will leave to form a new pack together. As such, African wild dog packs tend to average more males than females.

African wild dogs are not territorial animals. This is reflected in the lack of territorial urine marking, which is observed in most canid species. Occasional urine marking is seen in the alpha male and female, but not for territorial purposes. Because African wild dogs are non-territorial and do not have exclusive ranges, their home ranges can vary in size from 200 to 2,000 square kilometers.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

Diurnal, CrepuscularMOVEMENT PATTERN

Non-Migrant

Diet

African wild dogs are generalist carnivorous predators and mostly hunt medium-sized antelope that are about twice their weight or larger. Whereas they weigh 20–30 kilograms, their prey average around 50 kilograms, and may be as large as 200 kilograms.

In most areas, the African wild dog’s principal prey are impala (Aepyceros melampus), greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), Thomson’s gazelle (Eudorcas thomsonii) and common wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus). Small antelope, such as dik-dik (Madoqua spp.), steenbok (Raphicerus campestris) and duiker (tribe Cephalophini), such as common duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), are important in some areas, and warthogs (Phacochoerus spp.) are also taken in some populations. They will give chase of larger species, such as common eland (Tragelaphus oryx), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), and zebra (genus Equus), but rarely kill such prey unless they are old, sick, or injured.

African wild dogs also take very small prey such as hares, lizards, and even eggs, but these make a very small contribution to their diet. For the most part, the African wild dog does not eat plants or insects, except for small amounts of grass.

African wild dogs also occasionally kill livestock and important game animals, but will never scavenge, no matter how fresh the kill is.

African wild dogs tolerate scavengers at their kills, except for spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta). They drive off hyenas, sometimes injuring or killing them.

On occasion, some of the food African wild dogs get from larger kills may be cached, though very often they never return to the cached food.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Pursuit

Prey

Lesser Kudu

Steenbok

Common Duiker

Greater Kudu

Cape Scrub Hare

Common Wildebeest

Thomson’s Gazelle

Common Eland

Impala

Waterbuck

African Buffalo

Common Warthog

Reproduction

Each African hunting dog pack has a dominant breeding pair. This pair can be identified by their increased tendency to urine mark. They are normally the only pair of pack members to mate and they tend to remain monogamous for life. Their life expectancy is approximately ten years. Generally the dominant pair prevents subordinates from breeding. Breeding suppression between females may often result in aggressive interactions. Occasionally a subordinate female is allowed to mate and rear young.

The African wild dog reaches sexual maturity at approximately 12 to 18 months, though they usually do not mate until much later. The youngest recorded reproduction of a female was at 22 months old.

Gestation is approximately ten weeks and pups are usually born between March and July. Litter sizes can vary considerably, from 2 to 20 pups, with an average of 8 pups. The smaller litter sizes have been recorded from animals in captivity.

Breeding females gives birth to their litters in grass-lined burrows, usually an abandoned aardvark (Orycteropus afer) hole. The pups remain in the den with their mother for three to four weeks.

The interval between litters is normally 12 to 14 months.

African wild dogs take part in cooperative breeding, meaning that every member of the pack cares for the young. Once African wild dog pups are brought out of the den, they become the responsibility of the whole pack.

Pups nurse from other females in the pack as well as from their mother. Weaning can occur as early as 5 weeks.

BREEDING SEASON

March-JuneBREEDING INTERVAL

12-14 MonthsCOPULATION

1 MinutePARENTAL INVESTMENT

Cooperative Breeding, MaternalGESTATION

60-80 DaysBIRTHING SEASON

March-JulyLITTER

2-20MAMMAE

12-14WEANING

35-90 DaysSEXUAL MATURITY

12-18 Months

Ecology

African wild dogs, especially their young, are preyed on by lions (Panthera leo), spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta), and Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus). As such, the wild dogs choose habitats with low concentration of these predators.

African wild dogs are very reluctant to venture into water where they easily fall prey to crocodiles. Because of this reluctance, animals the dogs prey on can escape by fleeing to bodies of water.

Predation by lions, and perhaps competition with spotted hyaenas, contribute to keeping African wild dog numbers below the level that their prey base could support.

Across most of its geographical range, there is minimal utilization of the African wild dog. There is evidence of localized traditional use in Zimbabwe, but this is unlikely to threaten the species’ persistence. There are also some reports of trade in captive and wild-caught animals from southern Africa; the possible impact of such trade is currently being assessed.

Predators

Lion

Nile Crocodile

Spotted Hyaena

Human

Conservation

African wild dogs are considered an endangered species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Speciesbecause they have disappeared from much of their former range. They are also listed as Endangered by the United States Endangered Species Act.

Population

The African wild dog population is currently estimated at approximately 6,600 adults in 39 subpopulations, of which only 1,400 are mature individuals. With such low population estimates, the African wild dog is Africa’s second most endangered carnivore after the Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis). The largest areas contain only relatively small wild dog populations. For example, the Selous Game Reserve, with an area of 43,000 km² (about the size of Switzerland), is estimated to contain about 800 African wild dogs. Most reserves, and probably most African wild dog populations, are smaller. For example, the population in Niokolo-Koba National Park and buffer zones (about 25,000 km²) is likely to be not more than 50–100 dogs. Such small populations are vulnerable to extinction. Given uncertainty surrounding population estimates, and the species’ tendency to population fluctuations, the largest subpopulations might well number less than 250 mature individuals, thereby warranting listing as Endangered under criterion C2a(i).

MATURE INDIVIDUALS

1,409FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

The population size of the African wild dog is continuing to decline as a result of ongoing habitat loss and fragmentation, conflict with human activities, and infectious diseases that are spread by domestic animals. The principal threat to African wild dogs is habitat fragmentation, which increases their contact with people and domestic animals, resulting in human-wildlife conflict and transmission of infectious disease.

The important role played by human-induced mortality has two long-term implications. First, it makes it likely that, outside protected areas, African wild dogs may be unable to coexist with increasing human populations unless land use plans and other conservation actions are implemented. Second, African wild dog ranging behavior leads to a very substantial edge effect, even in large reserves. Simple geometry dictates that a reserve of 5,000 kilometers² contains no point more than 40 kilometers from its borders – a distance well within the range of distances traveled by a pack of African wild dogs in their usual ranging behavior. Thus, from an African wild dog’s perspective, a reserve of this size (fairly large by most standards) would be all edge. As human populations rise around reserve borders, the risks to African wild dogs venturing outside are also likely to increase. Under these conditions, only the very largest unfenced reserves will be able to provide any level of protection for African wild dogs.

Even in large, well-protected reserves, or in stable populations remaining largely independent of protected areas, as in northern Botswana, African wild dogs live at low population densities. Predation by lions (Panthera leo), and perhaps competition with spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta), contribute to keeping African wild dog numbers below the level that their prey base could support. Such low population density brings its own problems and are vulnerable to extinction. Problems of small population size will be exacerbated if, as seems likely, small populations occur in small reserves or habitat patches. Animals inhabiting such areas suffer a strong edge effect. Thus, small populations might be expected to suffer disproportionately high mortality as a result of their contact with humans and human activity.

Catastrophic events such as outbreaks of epidemic disease may drive the African wild dog to extinction when larger populations have a greater probability of recovery. Such an event seems to have led to the local extinction of the small African wild dog population in the Serengeti ecosystem on the Kenya-Tanzania border.

RESIDENTIAL & COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Housing & Urban Areas, Commercial & Industrial AreasAGRICULTURE & AQUACULTURE

Annual & Perennial Non-Timber Crops, Livestock Farming & RanchingENERGY PRODUCTION & MINING Oil & Gas Drilling, Mining & Quarrying

TRANSPORTATION & SERVICE CORRIDORS

Roads & RailroadsBIOLOGICAL RESOURCE USE

Hunting & Trapping Terrestrial Animals, Logging & Wood HarvestingHUMAN INTRUSIONS & DISTURBANCE

War, Civil, Unrest, & Military ExercisesINVASIVE & OTHER PROBLEMATIC SPECIES, GENES, & DISEASES

Invasive Non-Native/Alien Species/Diseases, Viral/Prion-Induced DiseasesCLIMATE CHANGE & SEVERE WEATHER

Temperature Extremes

ACTIONS

Conservation strategies have been developed for the African wild dog in all regions of Africa. Many range states have used these strategies as templates for their own national action plans.

Although each regional strategy was developed independently through a separate participatory process, the three strategies have a similar structure, comprising objectives aimed at improving coexistence between people and African wild dogs, encouraging land use planning to maintain and expand wild dog populations, building capacity for wild dog conservation within range states, outreach to improve public perceptions of wild dogs at all levels of society, and ensuring a policy framework compatible with wild dog conservation.

In South Africa, predator-proof fencing around small reserves has proved reasonably effective at keeping dogs confined to the reserve, but such fencing is not 100% effective and is unlikely to be long-term beneficial for wildlife communities.

The Painted Dog Conservation is a center that offers African wild dogs a refuge from poachers and rehabilitation when they’re injured. The center focuses on working with impoverished local villagers and has started economic development programs for nearby villages. The program’s goal is for local people to benefit from the African wild dog’s presence and gain stable income to prevent the need for wildlife poaching. This model would be sustainable for the protection of all species, not just African wild dogs. The Painted Dog Conservation also runs a children’s camp for school groups, sponsored by donors at $60 per child. At the camp, children can learn that African wild dogs don’t attack humans or prey heavily on livestock. They also learn to differentiate between spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta) and African wild dogs, especially as livestock is most often killed by hyenas, rather than wild dogs.

Several pieces of information are needed to enable more effective conservation of African wild dogs. Development is needed on cost-effective methods for surveying African wild dogs across large geographical scales. This is crucial as surveys of African wild dog distribution and status are needed, particularly in Algeria, Angola, the Central African Republic, Chad, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan. Determining the landscape features which facilitate or prevent wild dog movement over long distances will also promote or block landscape connectivity. Development is also needed for locally-appropriate and effective means to reduce conflict between wild dogs and farmers. Because contact with people, and thus domestic animals, results in the transmission of infectious disease, techniques that will be most effective and sustainable for protecting wild dogs from disease also need to be established.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Animal Corner. (2019). African wild dog. Animal Corner.

- BBC Studios. (2019, February 9). What’s in a name? Why we call them painted wolves. BBC.

- Canadian Museum of Nature. (2016, November 25). African Wild Dog. Natural History Notebooks.

- Davies, H. & Du Toit, J. T. (2004). Anthropogenic factors affecting wild dog Lycaon pictus reintroductions: A case study in Zimbabwe. Oryx, 38, 32-39.

- Davies-Mostert, H., Mills, M. G. L., & Macdonald, D. W. (2009). A critical assessment of South Africa’s managed metapopulation strategy for African wild dogs. In M. W. Hayward & M. J. Somers (Eds.), Reintroduction of Top Order Predators (1 ed.) (pp. 10-42). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- Edwards, J. M. (2009, December). Conservation genetics of African wild dogs Lycaon pictus (Temminck, 1820) in South Africa.(Doctoral dissertation). University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Estes, R. D. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: The University of California Press.

- Girman, D., Mills, M. G. L., Geffen, E., & Wayne, R. K. (1997). A molecular genetic analysis of social structure, dispersal, and interpack relations of the African wild dog (Lycaon pictus). Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology, 40, 187-198.

- Hayward, M. W. & Somers, M. J. (2009). Reintroduction of Top Order Predators (1 ed.). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

- Kingdon, J. (1997). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Kristof, N. (2010, April 14). Every (wild) dog has its day. The New York Times.

- Malcolm, J. R. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2001). Recent records of African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) from Ethiopia. Canid News, 4(2).

- Marsden, C. D., Woodroffe, R., Mills, M. G. L., McNutt, J. W., Creel, S., Groom, R., Emmanuel, M., Cleaveland, S., Kat, P., Rasmussen, G. S. A., Ginsberg, J., Lines, R., AndrÉ, J.-M., Begg, C., Wayne, R. K., & Mable, B. K. (2012). Spatial and temporal patterns of neutral and adaptive genetic variation in the endangered African wild dog (Lycaon pictus). Molecular Ecology, 21, 1379-1393.

- Mulheisen, M., C. Allen, and C. Allen (2002). Lycaon pictus. Animal Diversity Web.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker’s Mammals of the World (6 ed., Vol. 2). Baltimore: MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Sillero-Zubiri, C., Hoffmann, M., & Macdonald, D.W. (Eds.). (2004, January). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan.. Gland, Switzerland, & Cambridge, UK: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

- South Sudan Wildlife Service. (2010, December). National Action Plan for the Conservation of Cheetahs and African Wild Dogs in South Sudan. Juba, South Sudan: South Sudan Wildlife Service.

- Stuart, C. & Stuart, T. (2007). Stuart’s Field Guide to the Mammals of Southern Africa. (4 ed.) Cape Town, Africa: Struik Publishers.

- The Wikimedia Foundation. (2019, May 7). African wild dog. Wikipedia.

- Wildlife Africa CC. (2004, September 9). Wildlife Africa – Wild Dog Behavior. WildlifeAfrica.

- Wilson, D. E. & Reeder, D. M. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3 ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Woodroffe, R., Ginsberg, J. R., & Macdonald, D. W. (1997). The African Wild Dog: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland, & Cambridge, UK: IUCN Canid Specialist Group, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

- Woodroffe, R. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (2012). Lycaon pictus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T12436A16711116.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). Order Carnivora. In: D. E. Wilson & D. M. Reeder (Eds.), Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3 ed.) (pp. 532-628). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.