PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The butterfly viper, also known as the rhinoceros viper, is a puff adder endemic to central and western Africa. As an ambush predator, this carnivorous snake relies on camouflage as it waits for prey. After striking, it sinks its hollow fangs into its victim and delivers a deadly hemotoxic venom.

Physiology

The butterfly viper is a large, stout, heavy-bodied snake. Adult butterfly vipers have an average total length, from body to tail, of 60-107 centimeters, or 23-42 inches. Maximum total lengths of up to 1.2 meters, or 47.2 inches, are possible, but are an exception. Some butterfly vipers have been reported to reach 2.1 meters, or 7 feet. Butterfly vipers display sexual dimorphism as females are usually the larger of the two monomorphic sexes.

The butterfly viper’s midbody has 31–43 dorsal scale rows. There are 117–140 ventral scales and a single anal scale. There are 12-32 paired subcaudals, enlarged plates on the underside of the tail, with males having a higher count of 25–30 than females with 16–19. The butterfly viper’s scales are so rough and heavily keeled that they sometimes inflict cuts on handlers when the snakes struggle.

One of the butterfly viper’s most distinguishing characteristics is its small, flattened, narrow, triangular-shaped head. The head is considerably smaller in size than its body and has a large, dark triangular, arrow-shaped marking on the back. The butterfly viper’s neck is thin and its eyes are small and set well forward.

Butterfly vipers have a partially prehensile tail that aids their climbing behavior. Holding a butterfly viper by the tail is not safe as it can use it to fling itself upwards and strike.

The butterfly viper has a pair of hollow fangs in its mouth. These fangs are not large, rarely more than 1.5 centimeters, or 0.59 inches, long. These fangs penetrate deep into the snake’s victim, allowing small doses of venom to flow into the wound. The butterfly viper has the ability to control the movement of its fangs. When not in use, the fangs are folded up into the roof of the snake’s mouth. As such, the butterfly viper may open its mouth without the fangs flipping down into place. As is true with all snakes in the Viperidae family, the butterfly viper sheds its fangs periodically, every 6-10 weeks.

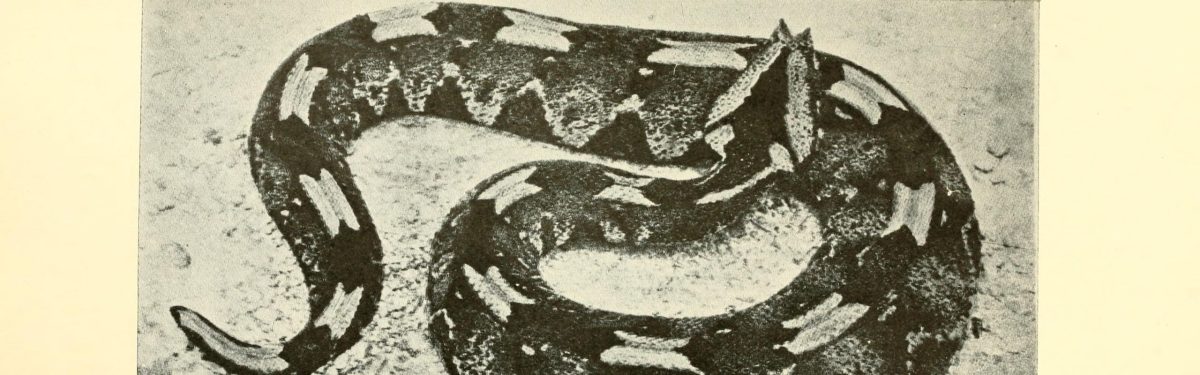

The butterfly viper is often considered one of the most beautiful of all snakes because of its incredible coloration. The color pattern of the butterfly viper consists of a series of 15–18 blue or blue-green, oblong markings, each with a lemon-yellow line down the center. These are enclosed within irregular, black, rhombic blotches. A series of dark crimson triangles run down the flanks, narrowly bordered with green or blue. Many of the lateral scales have white tips, giving the snake a velvety appearance. The top of the head is blue or green, overlaid with a distinct black arrow mark. The belly is dull green to dirty white, strongly marbled, and blotched in black and gray.

The color patterns vary among individuals and the degree of light and dark colors dependent on the snake’s habitat. Western specimens are more blue, while those from the East are more green. After they shed their skins, the bright colors fade quickly as silt from their generally moist habitat accumulates on the rough scales. The vivid coloration of the snake gives it excellent camouflage in the dappled light conditions of the forest floor, making it almost invisible. Thus, its brilliant coloration is an adaptive feature. Darker colors allow the snake to blend well with the jungle floor.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

Larger Females with Less SubcaudalsBODY LENGTH

60-107 cm. / 23-42 in.DORSAL SCALE ROWS

31-43VENTRAL SCALES

117-140PAIRED SUBCAUDALS

12-32ANAL SCALES

1LIFESPAN

8.3 yr.

Images

Taxonomy

The butterfly viper is categorized in the Bitis genus and is one of the fifteen species of puff adders. Members of the Bitis genus, including the butterfly viper, are called puff adders because of their characteristic threat display. When excited, these venomous snakes have the ability to enlarge their size considerably by inflating and deflating their bodies. This creates the puffed look that is approximately twice the normal size of the snake’s body. Puff adders also make an extremely loud hissing noise through their nose as part of their respiratory function and puff loudly.

The butterfly viper’s closest relative is the rhinoceros viper (Bitis rhinoceros). The butterfly viper has a brighter color pattern and a narrower head than the rhinoceros viper. The rhinoceros viper is also missing the distinct, black arrow mark on the butterfly viper’s head, and instead has a single dark stripe running down the back of its head.

No subspecies of the butterfly viper are currently recognized.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

ReptiliaORDER

SquamataFAMILY

ViperidaeGENUS

BitisSPECIES

nasicornisSUBSPECIES

None

Etymology

The butterfly viper is also known as the rhinoceros viper, river jack, rhinoceros horned viper, and horned puff adder.

Historically, this species was most commonly referred to as the rhinoceros viper, but this introduced confusion after the reclassification of the closely related species, Bitis rhinoceros, also known as the rhinoceros viper. The rhinoceros viper was historically recognized as a subspecies of the Gaboon viper, with the scientific name of Bitis gabonica rhinoceros, until 1999 when genetic differences were discovered. The subspecies was found to be as genetically different from the Gaboon viper as it was from the butterfly viper and thus the rhinoceros viper was designated a separate species and given the scientific name Bitis rhinoceros. The common name butterfly viper is therefore more distinct and preferred for Bitis nasicornis to avoid confusion.

The butterfly viper is known as the rhinoceros viper because of the distinctive set of two or three horn-like scales it has above each nostril at the end of the nose. The front pair of scales may be quite long.

The butterfly viper is often called the River Jack because it inhabits tropical forests, often near water, or some sort of swampy environment.

ALTERNATE

Arrowhead Viper,/Nose-Horned Viper, Horned Puff Adder, Rhino/Rhinoceros Horned Viper, River JackGROUP

Den, Generation, Nest, PitYOUNG

Hatchling, Neonate, Snakelet

Region

The butterfly viper is endemic to central and western Africa.

In West Africa, they are found from Guinea to Ghana. In central Africa, they inhabit the Central African Republic, Southern Sudan, Cameroon, Gabon, Congo, DR Congo, Angola, Rwanda, Uganda, and western Kenya. Reports as far as southern Zaire have also been documented.

The type locality is listed only as interior parts of Africa.

Its range is more restricted than the Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica).

EXTANT

Angola, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Dominican Republic, Kenya, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Rwanda, Sudan, Uganda, Zaire

Habitat

The butterfly viper inhabits forested areas and tropical forests and rarely ventures into woodlands. It often lives near water, or some sort of swampy environment, but can be found in relatively dry forest areas.

When butterfly vipers were studied, three habitat types were found along the various transects: mature rain forest, secondary rain forest, and swamp forest.

Co-Habitants

Hippopotamus

African Elephant

Secretarybird

Jameson’s Mamba

Gaboon Viper

Puff Adder

Behavior

Primarily nocturnal, the butterfly viper hides during the day in leaf litter and holes or around fallen trees and tangled roots of forest trees.

Unless provoked or hungry, the butterfly viper will not bite. It is generally considered a slow-moving, somewhat placid animal, less so than the Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica), but not as bad-tempered as the puff adder (Bitis arietans). A captive specimen was described as hardly ever leaving its hide box, even when hungry. The viper once waited for three days for a live mouse to enter its hide box before striking.

Generally, the butterfly viper is considered somewhat slow in locomotion. As with other snakes, the butterfly viper uses its scales for movement. Stretching its skin across its ribs, then releasing tension, gives the butterfly viper the ability to slither across the jungle floor quite efficiently.

When the butterfly viper gets excited, it can strike faster than the blink of an eye with extremely deadly accuracy. These snakes can strike in any direction with equal speed and their striking range is surprisingly long, sometimes as long as half the snake’s length. They are capable of striking quickly, forwards or sideways, without coiling first or giving a warning.

When approached, butterfly vipers often reveal their presence by hissing, said to be the loudest hiss of any African snake—almost a shriek. Puff adders are known to make extremely loud hissing noises through their noses as part of their respiratory functions. They also puff loudly.

Although mainly terrestrial, the butterfly viper has been known to climb into trees and thickets in search of food. They have been found up to 3 meters, or 9.8 feet, above the ground.

Butterfly vipers are sometimes found in shallow pools and have been described as powerful swimmers.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

NocturnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Non-Migrant

Diet

The butterfly viper is carnivorous and generally feeds on smaller prey than the closely related, Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica). Small mammals are the main staple of the butterfly viper’s diet, but the snakes are also reported to eat amphibians, such as toads and frogs, and even fish in wetland habitats.

One long-term captive specimen, regularly fed killed mice and frogs, always held on to its prey for several minutes after a strike before swallowing.

The butterfly viper is an ambush predator, relying on cryptic coloration as camouflage to hide from its prey. Preferring to hunt by ambush, the butterfly viper spends much of its life motionless, waiting for prey to wander by.

Like all vipers, the butterfly viper is venomous. It is considered to be one of the most dangerous and venomous snakes of Africa. Unlike the Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica) who uses a considerably large amount of venom, just small doses of the butterfly viper’s venom can be deadly.

This venom attacks the circulatory system of the snake’s victim, destroying tissue and blood vessels. This causes internal bleeding and massive hemorrhaging. In only a few detailed reports of human envenomation, massive swelling, which may lead to necrosis, had been described. Some bites cause paralysis, some cause swelling, and most of them cause shock, where the blood stops coagulating and people either bleed from the tissues or fluid leaks out of their blood vessels.

Like most other venomous snakes, the butterfly viper has a single venom with both neurotoxic, as well as hemotoxic properties, but the hemotoxicity is much more dominant. Relatively little is known about the toxicity and composition of the butterfly viper’s venom. The venom is supposedly slightly less toxic than those of the Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica) and puff adder (Bitis arietans). In mice, the intravenous LD50 is 1.1 milligram per kilogram. In rabbits, the venom is apparently slightly more toxic than that of the Gaboon viper. The maximum wet venom yield is 200 milograms. One study reported this venom has the highest intramuscular LD50 value—8.6 milligram per kilogram—of five different viperid venoms tested (puff adder, Gaboon viper, butterfly viper, Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), and asp viper (Vipera aspis). Another showed little variation in the venom potency of these snakes, whether they were milked once every two days or once every three weeks.

Because of the butterfly viper’s restricted geographic range, few bites have been reported and no statistics are available, but at least one death has occurred. In 2003, a man in Dayton, Ohio, who was keeping a specimen as a pet, was bitten and subsequently died.

Surviving a bite from the butterfly viper can sometimes depend on the location of the bite. Rarely, people will be invenomated right into a vein, shooting up the venom, as opposed to simply getting it into a muscle and slowly having it leak into the body. At least one antivenom protects specifically against bites from this species: India Antiserum Africa Polyvalent.

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Ambush

Reproduction

The butterfly viper is a viviparous animal, giving live birth to 6-38 young. In West Africa, the butterfly gives birth at the start of the rainy season in March and April. In eastern Africa, the breeding season is indefinite.

Gestation takes about seven months, which suggests a breeding cycle of two to three years. A five-year breeding cycle may also be possible.

Young butterfly vipers are approximately 18-25 centimeters, or 7-10 inches, brilliantly colored, and venomous. There is no real parental care once the offspring are born.

BREEDING SEASON

March-AprilBREEDING INTERVAL

2-3 YearsPARENTAL INVESTMENT

NoneGESTATION

7 MonthsLITTER

6-38

Ecology

Unsurprisingly, adult butterfly vipers have no known predators. Juveniles may be eaten by secretarybirds (Sagittarius serpentarius), large monitors (Varanus sp.), fish, cats and cobras (Naja sp.)

Given their incredible camouflage, one of the greatest threats to butterfly vipers is being trampled by large ungulates, such as African elephants (Loxodonta africana) or hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius). This threat is greatest in the winter, when the vipers move into more open habitats to absorb more solar radiation. During this time, the snakes spend a lot of time in clumps of dense vegetation, which likely protects them from being trodden upon.

Humans kill snakes out of fear, sport or persecution otherwise; some indigenous groups hunt them for meat. Though butterfly vipers have evolved a suite of defenses that render them virtually untouchable in their historic habitat, the snakes have no defenses against determined humans. By virtue of tools like rakes, shovels, guns, and axes, humans can kill the snakes from a safe distance. Fortunately for the vipers, they prefer undisturbed, primary forest habitats and aren’t often found in close proximity to civilization. In addition to direct persecution by humans, human-caused habitat destruction threatens butterfly vipers as well. The vipers depend on undisturbed forest habitat and cannot thrive in suburban or disturbed areas like some other snakes, such as the closely related puff adders (Bitis arietans).

Butterfly vipers are bred domestically and sold online in the exotic pet trade. Although most people would never see the butterfly viper in the wild, there are many who breed this extremely dangerous animal domestically. Like practically anything else, a butterfly viper can be purchased online. Listings have been found for baby vipers for $75.00 plus shipping and $125.00 for adult snakes.

Predators

Human

Secretarybird

Conservation

The butterfly viper has not been evaluated by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and is thus classified as Not Evaluated.

Population

Recent work in West Africa has has provided density estimates for a few large, forest-associated species such as the butterfly viper, Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica), and Jameson’s mamba (Dendroaspis jamesonii). The presence and density of the Gaboon viper and the butterfly viper were studied along several transects, during both dry and wet seasons, and at different times of day, in southern Nigeria, West Africa.

The detection probabilities for these vipers were modelled with a set of competing models, and the various models were ordered by Akaike Information Criterion procedures. The best models suggested that for the Gaboon viper, habitat types secondary rain forest and swamp forest were particularly important in detecting this species, especially during the rainy season at 08h00–16h00. For butterfly vipers, the best models had swamp forest and mature rain forest as site-covariates. Application of the multi-species model revealed that there were different detection functions if both species are present at a site, with a ‘negative’ interaction of occupancy between the species.

Females and males were similarly detectable in a logistic regression model, but feeding status and pregnancy slightly increased detection probability in a logistic regression model.

Viper density was modelled by a DISTANCE sampling procedure. The density of one species tended to be inversely correlated to the density of the other, suggesting that the rain-forest environment does not support abundant populations of both vipers when sympatric, and the two Bitis species subtly partition the habitat resources.

THREATS

Little information about the butterfly viper’s threats and conservation actions is available.

ACTIONS

Little information about the butterfly viper’s conservation actions is available.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Auliya, M. (2003). Hot trade in cool creatures: A review of the live reptile trade in the European Union in the 1990s, with a focus on Germany. Brussels, Belgium: TRAFFIC Europe.

- Firehouse. (2003, August 5). Ohio firefighter dies after bite from pet snake. Firehouse.

- ITIS. (2017). Bitis nasicornis. Integrated Taxonomic Information System On-line Database.

- Lenk, P., Herrmann, H.-W., Joger, U., & Wink, M. (1999, January). Phylogeny and taxonomic subdivision of Bitis (Reptilia: Viperidae) based on molecular ervidence. Kaupia, Darmstädter Beiträge zur Naturgeschichte, 8, 31–38.

- Lipsett, J. S. (2003, April). The rhinoceros viper. WhoZoo.

- Mallow D., Ludwig, D., Nilson, G. (2003). True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company.

- McDiarmid, R. W., Campbell, J. A., Touré, T. (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (Vol. 1). Washington, District of Columbia: Herpetologists’ League.

- Mehrtens J. M. (1987). Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York, NY: Sterling Publishers.

- Rogers, G. (2000). Bitis nasicornis. Animal Diversity Web.

- Spawls, S., Howell, K., Drewes, R., Ashe, J. (2004). A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa. London: A & C Black Publishers Ltd.

- Wallach, V. (2018, February 16). Rhinoceros viper. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- The Wikimedia Foundation. (2018, November 7). Bitis nasicornis. Wikipedia.