PHYSIOLOGY | IMAGES | ETYMOLOGY | TAXONOMY | GEOGRAPHY | BEHAVIOR | DIET | REPRODUCTION | ECOLOGY | CONSERVATION | FAUNAFACTS | VIDEO | SOURCES

The green turtle is the second largest species of sea turtle. As a migratory, cosmopolitan species, this species is found in shallow tropical and subtropical waters near the equator and will travel great lengths in order to return to its natal beach to lay the next generation of eggs. This endangered species is threatened by tourism, recreation, and fishing.

Physiology

Green turtles are the second largest overall species of sea turtles after the leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea). As hatchlings, green turtles have an average weight of 25-26 grams and are 5 centimeters long. Juveniles measure to about 40 centimeters in carapace length and subadults will measure between 70 to 100 centimeters. Adult green turtles, male or female, tend to be about 100 to 120 centimeters long in carapace length and weigh around 150 to 200 kilograms when reaching adulthood.

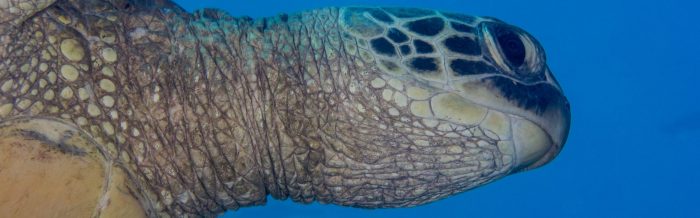

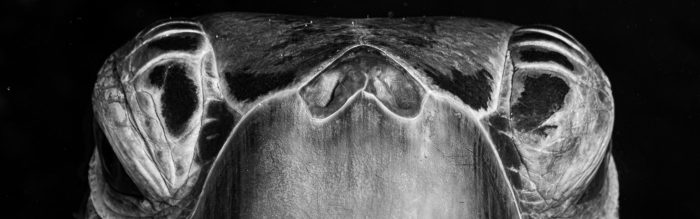

The green turtle’s skull shape is described as round and smooth. These marine turtles have short snouts and strong beaks that cover the bones of the jaw. Their jaws are short and serrated to properly rip and tear plants apart for consumption.

Green turtles have only one pair of prefrontal scales, although other species of sea turtles have multiple pairs. Hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata), for example, have two pairs of prefrontal scales.

Green sea turtles are black at hatching, but then change color over the course of their lives as the turtles mature. The coloration of juvenile green sea turtles has been found to be fairly uniform: the carapace and top of head light brown; the side of the head and dorsal surface of the flippers dark brown; the beak brown; the plastron, throat, and ventral surface of the flippers entirely creamish white, except for a few light brown scales distally located on the flippers.

Larger juvenile turtles occasionally have yellow or black streaks radiating peripherally on the carapace shields, the general color pattern of the entire dorsal surface becoming darker. All interscute areas on the carapace and interscale areas on the head and flippers are well defined and creamish-white.

Adult green turtle coloration, in contrast to that of the juveniles, shows considerable variation: the background coloration of the carapace and top of head ranges from dark brown to light green, generously infused with combinations of yellow, brown, and black; beak brown; pastron, throat, and ventral surface of the flippers creamish, except for scattered dark centered scales on the flippers.

Sexual dimorphism isn’t completely recognized in green turtles until early adulthood. As such, it is difficult to determine a green turtle’s sex until the animal is fully grown, at least 20 years old. Recently, however, researchers from the U.S. and Australia have developed a method to determine the sex of green sea turtles while the animals are still young via DNA and blood tests. There appears to be no easily recognizable difference in coloration between sexes.

Males and females differ morphologically by the length of their tail and cloacal openings. Female green sea turtles have smaller tails and a cloacal opening between the anus and tip of the tail. Male green turtles are slightly smaller in carapace length, have longer claws, and have longer tails where their reproductive organs are located. Their cloacal opening is located more posterior on the tail and past the end of their carapace.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

Larger Females with Shorter Tails & ClawsBODY LENGTH

99-153 cm. / 39-60 in.BODY MASS

150-395 kg. / 331-871 lb.LIFESPAN

27-80 yr.GENERATION LENGTH

35.5-49.5 yr.LOCOMOTION

Other

Images

Taxonomy

The green turtle is a member of the tribe Chelonini. A 1993 study clarified the status of genus Chelonia with respect to the other marine turtles. The carnivorous hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), and Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) and olive ridleys (Lepidochelys olivacea). Ridleys were assigned to the tribe Carettini. Herbivorous Chelonia warranted their status as a genus, while flatback (Natator depressus) was further removed from the other genera than previously believed.

The green turtle was originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Testudo mydas.

In 1868, Marie Firmin Bocourt named a particular species of sea turtle Chelonia agassizii, the black sea turtle. Later research determined Bocourt’s black sea turtle was not genetically distinct from C. mydas, and thus taxonomically not a separate species. These two species were then united as Chelonia mydas and populations were given subspecies status: C. mydas mydas referred to the originally described population, while C. mydas agassizi referred only to the Pacific population known as the Galápagos green turtle. This subdivision was later determined to be invalid and all species members were then designated Chelonia mydas. The oft-mentioned name C. agassizi remains an invalid junior synonym of C. mydas.

KINGDOM

AnimaliaPHYLUM

ChordataCLASS

ReptiliaORDER

TestudinesFAMILY

CheloniidaeGENUS

CheloniaSPECIES

mydasSUBSPECIES (4)

C. m. mydas (Atlantic) C. m. agassizi/agassizii (Eastern Pacific Black, Galápagos) C. m. carrinegra (Brown, Northeastern Pacific) C. m. japonica (West Pacific)

Etymology

The green turtle’s common name does not derive from any particular green external coloration of the turtle. Green turtles are so named because of the greenish color of their subdermal fat, which is only found in a layer between their inner organs and their shell.

As a species found worldwide, the green turtle has many local names. In the Hawaiian language it is called honu, and it is locally known as a symbol of good luck and longevity.

In 1868, Marie Firmin Bocourt named a particular species of sea turtle the black sea turtle, later recognized as the Galápagos green turtle subspecies.

ALTERNATE

Black Sea Turtle, Common Green Sea Turtle, Pacific Green TurtleGROUP

Bale, Dole, Nest, TurnYOUNG

Hatchling

Region

The green turtle has a circumglobal distribution, occurring throughout tropical and, to a lesser extent, subtropical waters (Atlantic Ocean – eastern central, northeast, northwest, southeast, southwest, western central; Indian Ocean – eastern, western; Mediterranean Sea; Pacific Ocean – eastern central, northwest, southwest, western central). Green turtles are highly migratory and they undertake complex movements and migrations through geographically disparate habitats.

Overall, the green turtle’s movements within the marine environment are less understood but it is believed that green turtles inhabit coastal waters and settle on the beaches of over 140 countries.

Nesting occurs in more than 80 countries worldwide. During the months that this species breeds, (June through August,) green sea turtles are most frequently found nesting on the coastlines of Cyprus and Turkey. They are also observed nesting on the beaches of Israel, Syria, Egypt and Libya.

In the Pacific Ocean, the largest nesting ground for green sea turtles remains the beaches of Raine Island of Australia. During high season, 18,000 individuals can be found nesting upon these sands.

Radio tagging nesting females shows that green sea turtles are migratory, and their non-breeding range includes locations from as far north as 40 degrees north to as far south as 40 degrees south. These areas include parts of the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and northern Indian Ocean.

EXTANT (BREEDING)

Guinea, Guinea-BissauREINTRODUCED

BermudaVAGRANT

Namibia, Pitcairn, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Wallis and FutunaEXTINCT

Cayman Islands, MauritiusUNCERTAIN

Bahamas, Benin, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, Cameroon, Chile, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, El Salvador, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Honduras, Israel, Liberia, Montserrat, Nigeria, Qatar, Samoa, Sudan, Taiwan, Togo, Western Sahara

Habitat

Like most sea turtles, green turtles are highly migratory and use a wide range of broadly separated localities and habitats during their lifetimes.

Upon leaving the nesting beach, it has been hypothesized that hatchlings begin an oceanic phase, perhaps floating passively in major current systems (gyres) that serve as open-ocean developmental grounds. After a number of years in the oceanic zone, these turtles recruit to neritic developmental areas rich in seagrass and/or marine algae where they forage and grow until maturity. Upon attaining sexual maturity, green turtles commence breeding migrations between foraging grounds and nesting areas that are undertaken every few years. Migrations are carried out by both males and females and may traverse oceanic zones, often spanning thousands of kilometers. During non-breeding periods, adults reside at coastal neritic feeding areas that sometimes coincide with juvenile developmental habitats.

Green turtles are a cosmopolitan species found in marine neritic, oceanic, intertidal, and coastal/supratidal habitats. They can be found in shallow tropical and subtropical waters as well as coastline beaches and forage in coastal areas with plentiful algae and sea grass.

MARINE NERITIC

Macroalgal/Kelp, Submerged SeagrassMARINE OCEANIC

EpipelagicMARINE INTERTIDAL

Sandy Shoreline, Beaches, Sand Bars, SpitsMARINE COASTAL/SUPRATIDAL

Coastal Sand Dunes

Co-Habitants

Golden Jackal

Jaguar

Tiger Shark

Saltwater Crocodile

Red Fox

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

Hawksbill Turtle

Vaquita

Behavior

Green turtles are normally solitary, but travel in large groups that usually originate from the same natal beach. They spend a lot of their time swimming, traveling about 20-90 kilometers a day, eating, diving, reproducing, and migrating.

Green turtles primarily use vision to detect plants and other prey and use visual displays when communicating. They also use a sense of wave propogation direction to help them navigate under water and rely on magnetic channels to assist their orientation in deep waters. The turtles’ inner ear can detect the acceleration and direction of waves, which assists their sense of direction.

Radio tagging nesting females shows that green sea turtles are migratory, and their non-breeding range includes locations from as far north as 40 degrees north to as far south as 40 degrees south. These areas include parts of the Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and northern Indian Ocean. Male and female green turtles use major current systems when migrating to their natal nesting beaches.

Green sea turtles will maintain home ranges throughout the year. These habitats include coastal feeding areas during the non-breeding season and natal beaches that the females visit during the nesting season. Adult green turtles have a home range that can expand from 3.8 ha to 642.2 ha. They are not known to actively defend a territory.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

DiurnalMOVEMENT PATTERN

Full Migrant

Diet

Because green sea turtles are highly mobile throughout their lives, their food choices are often opportunistic.

Green sea turtles begin their lives as omnivores and gradually shift to a more herbivorous diet.

As juveniles, green sea turtles will feast on small marine invertebrates and neustonic material like sea serpents (Hydrozoa), moss animals (Bryozoa), and sea hare eggs (Aplysia). They also consume large quantities of wetland plants such as api api (Avicennia schaueriana) and salt-water cord grass (Spartina alterniflora), which are commonly found in salt marshes.

Mature green turtles are mostly herbivorous and consume large quantities of sea grass and algae. Their diet consists of a variety of red and green algae such as: filamentous red alga (Bostrychia,) red moss (Caloglossa,) freshwater red algae (Compsopogon,) lobster horns (Polysiphonia,) sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca), green seaweed (Gayralia) and crinkle grass (Rhizoclonium).

PREFERENCE

GeneralistSTYLE

Forager

Reproduction

Green sea turtles are polygynandrous, meaning that, both, females and males will have multiple mates.

The green sea turtle reproduction process begins with the male searching for a female mate. Once a female has been found, the male will visually examine and approach the female, and the female will either submit or reject the male. If the female accepts, copulation will follow.

Female green turtles use two displays to communicate with males whether or not they wish to mate. Females will show approval of a mate by being completely submissive when being mounted by the male. They will clearly reject a male by either swimming away with their hind legs closed or biting a male if he gets too close. Female green turtles also have a refusal position, which consists of floating upward having their plastron facing the male and extending all limbs.

The male will mount his mate and grab onto her mating notches around her shoulders to assist in copulation. Copulation occurs in the shallow waters off the shore of nesting beaches. Green sea turtle copulation can last several hours, with the longest recorded mounting episode lasting 119 hours.

During the breeding season, actively mating green turtle pairs are often approached by several escort rival males that will latch on to the pair during copulation, for hours on end, in attempts to dislodge the mating male. These escort males may even attempt to remove the male connected to the female directly by biting at his soft fins with their harsh, sharp beaks. If the copulating male feels threatened by the escorts, he might remove himself from the female briefly to drive off the other males.

Female green turtles are known to revisit their natal beaches in 2-4 year intervals to breed from June to September. They average a total of 15 days between initial mounting by a male to the time they attempt to nest on their respective natal beaches. If they don’t return to their natal beach, they will select a beach with similar sand texture and color.

Once females find a suitable beach for their nest sites with accessible sloping platforms, they begin clearing the area of debris. Afterwards, the female digs a hole in the sand with her front legs and lays a clutch of eggs. After laying eggs, she fills the nest with sand as a way to camouflage and conceal the eggs, then she returns to the sea. There is no parental investment by green turtles beyond the mother’s egg-laying and camouflaging of the nest.

Female green turtles lay white, soft-shelled eggs that measure 35-58 millimeters in diameter. One female can lay 1-9 clutches in a single nesting season, but tends to average around 3. Each of these clutches can include 75-200 eggs. Incubation takes 30-90 days, depending on whether or not it is the wet or dry season. Incubation typically takes longer in the wet season.

Like many turtles, green sea turtles’ development is affected by temperature. Eggs that are laid in cooler environments, less than 28.5°Celsius, tend to produce more males than females, and warm nests, greater than 30.3°Celsius, are known to hatch more females than males.

Immediately after green turtles eggs hatch, the juvenile sea turtles begin their journey towards the ocean. From there, the hatchlings will begin the juvenile portion of their lives which can last 27-80 years before reaching full maturity. Juveniles are known to spend several years drifting in the open ocean as they grow and mature. Once the juveniles have matured, they will return to their natal beach for mating.

Green sea turtles are black at hatching, but then change color over the course of their lives as the turtles mature. The coloration of juvenile green sea turtles has been found to be fairly uniform: the carapace and top of head light brown; the side of the head and dorsal surface of the flippers dark brown; the beak brown; the plastron, throat, and ventral surface of the flippers entirely creamish white, except for a few light brown scales distally located on the flippers.

Larger juvenile turtles occasionally have yellow or black streaks radiating peripherally on the carapace shields, the general color pattern of the entire dorsal surface becoming darker. All interscute areas on the carapace and interscale areas on the head and flippers are well defined and creamish-white.

Juvenile green turtles are said to be faster swimmers than other sea turtles such as loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) and olive ridleys (Lepidochelys olivacea) due to the way green turtle hatchlings stroke their foreflippers.

BREEDING SEASON

June-SeptemberBREEDING INTERVAL

2-4 YearsBROOD

1-9COPULATION

119 HoursPARENTAL INVESTMENT

NoneINCUBATION

45-75 DaysBIRTHING SEASON

June-SeptemberCLUTCH

75-200INDEPENDENCE

BirthSEXUAL MATURITY

27-50 Years

Ecology

Green turtles play a role in their ecosystem by facilitating nutrient turnover and sea grass regrowth. As the turtles graze on sea grass and algae, they provide nitrogen-rich fertilizer in the form of fecal matter.

Green turtle hatchlings are at a higher risk of predation than adult green sea turtles.

Eggs are preyed upon by multiple land mammals, reptiles, and crustaceans. Some of these mammals include: jaguars (Panthera onca), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), feral dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), golden jackals (Canis aureus) and humans (Homo sapiens). Young green sea turtles are also consumed by crabs (Brachyura) and saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porous) which can attack on land or in the water. The only defense mechanism of hatchlings is swarming in large groups toward the ocean.

Once the hatchlings reach the water, they face a new group of predators such as tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) and oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus). Evidence of healed shark bites is sometimes witnessed through damaged rear flippers within juveniles, but is not often seen in adults.

Juvenile and mature sea turtles are also preyed on by sharks. Mature green sea turtles’ best form of protection from their predators is their large hard shells. When females come on land to nest, their heads and limbs become vulnerable and easily accessible by predators. Green turtles are also hunted by humans for meat.

Green sea turtles suffer from parasitic trematode eggs known as flukes. These trematodes cause inflamed cardiovascular tissue that infect turtles and commonly result in death. Species of flukes that are found in green turtles include: Learedius leardei, Carettacola hawaiiensis, Hapalotrema dorsopora, and Hapalotrema postorchis.

There are no known adverse effects of the green turtle on humans.

Although many countries have established laws protecting sea turtles, green sea turtles are still poached for their eggs and meat in certain areas around the world, such as South East Asia. The shells are also displayed as decoration or used to make jewelry.

Perhaps the most detrimental human threats to green turtles are the intentional harvests of eggs and adults from nesting beaches and juveniles and adults from foraging grounds. Unfortunately, harvest remains legal in several countries despite substantial subpopulation declines.

Predators

Human

Saltwater Crocodile

Golden Jackal

Oceanic Whitetip Shark

Tiger Shark

Jaguar

Dog

Red Fox

Conservation

The green turtle is classified as Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

Population

Analysis of historic and recent published accounts indicate extensive subpopulation declines in all major ocean basins over the last three generations as a result of overexploitation of eggs and adult females at nesting beaches, juveniles and adults in foraging areas, and, to a lesser extent, incidental mortality relating to marine fisheries and degradation of marine and nesting habitats. Analyses of subpopulation changes at 32 Index Sites distributed globally show a 48% to 67% decline in the number of mature females nesting annually over the last 3–generations.

FRAGMENTATION

Not Fragmented

THREATS

Green turtles, like other sea turtle species, are particularly susceptible to population declines because of their vulnerability to anthropogenic impacts during all life-stages: from eggs to adults.

A number of incidental threats impact green turtles around the world. These threats affect both terrestrial and marine environments and include bycatch in marine fisheries, habitat degradation at nesting beaches and feeding areas, and disease. Mortality associated with entanglement in marine fisheries is the primary incidental threat. Responsible fishing techniques include drift netting, shrimp trawling, dynamite fishing, and long-lining.

Degradation of both nesting beach habitat and marine habitats also play a role in the decline of many green turtle stocks. Nesting habitat degradation results from the construction of buildings, beach armoring and re-nourishment, and sand extraction. These factors may directly, through loss of beach habitat, or indirectly, through changing thermal profiles and increasing erosion, serve to decrease the quantity and quality of nesting area available to females, and may evoke a change in the natural behaviors of adults and hatchlings.

The presence of lights on or adjacent to nesting beaches alters the behavior of nesting adults and is often fatal to emerging hatchlings as they are attracted to light sources and drawn away from the water. Because most species of sea turtles are nocturnal nesters, artificial lighting of nesting beaches may present an environmental modification that disrupts visual cues. Increasing human development adjacent to sea turtle nesting beaches worldwide has brought with it increasing levels of artificial illumination. Correlations between lighted, developed beaches and lower nesting activity by sea turtles have been observed.

Studies suggest that MV luminaires and other broad-spectrum lighting types have the potential to disrupt the nesting of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) and green turtles. Some turtles have been misdirected by lighted luminaires, (primarily mercury vapor,) on their return to the ocean following nesting attempts. LPS luminaires may be an acceptable alternative where lighting on nesting beaches cannot be completely extinguished. Lighting beaches with LPS luminaires has been shown to have no significant effect on nesting in either species.

Due to warming climates, 90% of green turtles at the Great Barrier Reef, the largest green turtle colony, are hatching female. Like many turtles, green sea turtles’ development is affected by the temperature of the sand surrounding the eggs. Eggs that are laid in cooler environments, less than 28.5°Celsius, tend to produce more males than females, and warm nests, greater than 30.3°Celsius, are known to hatch more females than males. If this trend continues, this could lead to the green sea turtle’s extinction. It’s likely that the surplus of females has gone unnoticed because of the difficulty of determining a green turtle’s sex. Because sexual dimorphism isn’t completely recognized in green turtles until early adulthood, it’s difficult to determine the sex until the animal is fully grown, at least 20 years old. Researchers are currently examining the effect of rising temperatures on green sea turtle populations along the coasts of Hawaii and on the island of Saipan in the western Pacific.

Habitat degradation in marine environments results from increased effluent and contamination from coastal development, construction of marinas, increased boat traffic, and harvest of nearshore marine algae resources. Combined, these impacts diminish the health of coastal marine ecosystems and can adversely affect green turtles. Degradation of marine habitats has also been implicated in the increasing prevalence of the tumor-causing Fibropapilloma disease.

RESIDENTIAL & COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Tourism & Recreation AreasBIOLOGICAL RESOURCE USE

Fishing & Harvesting Aquatic Resources

ACTIONS

Green turtles have been afforded legislative protection under a number of treaties and laws. Among the more globally relevant designations are those of Endangered by the World Conservation Union; Annex II of the SPAW Protocol to the Cartagena Convention, a protocol concerning specially protected areas and wildlife; Appendix I of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora); and Appendices I and II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). A partial list of the International Instruments that benefit green turtles includes the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles, the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation and Management of Marine Turtles and their Habitats of the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia (IOSEA), the Memorandum of Understanding on ASEAN Sea Turtle Conservation and Protection, the Memorandum of Agreement on the Turtle Islands Heritage Protected Area (TIHPA), and the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Conservation Measures for Marine Turtles of the Atlantic Coast of Africa.

As a result of these designations and agreements, many of the intentional impacts directed at sea turtles have been lessened: harvest of eggs and adults has been slowed at several nesting areas through nesting beach conservation efforts and an increasing number of community-based initiatives are in place to slow the take of turtles in foraging areas. In regard to incidental take, the implementation of Turtle Excluder Devices has proved to be beneficial in some areas, primarily in the United States and South and Central America. However, despite these advances, human impacts continue throughout the world. The lack of effective monitoring in pelagic and near-shore fisheries operations still allows substantial direct and indirect mortality, and the uncontrolled development of coastal and marine habitats threatens to destroy the supporting ecosystems of long-lived green turtles.

FaunaFacts

Video

SourceS

- Ackerman, R. A. (1997, January). The nest environment and the embryonic development of sea turtles. In P. L. Lutz & J. A. Musick (Eds.), The Biology of Sea Turtles (pp. 83-106). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Aguirre, A. A., Spraker, T. R., Balazs, G. H., & Zimmerman, B. (1998). Spirorchidiasis and fibropapillomatosis in green turtles from the Hawaiian islands. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 34(1), 91-98.

- Alfaro, L. D., Montal, V., Guimaraes, F., Saenz, C., Cruz, J., Morazan, F., & Carrillo, E. (2016). Characterization of attack events on sea turtles (Chelonia mydas and Lepidochelys olivacea) by jaguar (Panthera onca) in Naranjo Sector, Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. International Journal of Conservation Science, 7(1), 101-108.

- Aragones, L., Lawler, I., Foley, W., & Marsh, H. (2006, November). Dugong grazing and turtle cropping: Grazing optimization in tropical seagrass systems. Oecologia, 149(4), 635-647.

- Arthur, K., Boyle, M. C., & Limpus, C. J. (2008, June). Ontogenetic changes in diet and habitat use in green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) life history. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 362, 303-311.

- BBC. (2016, December 12). The Planet Earth II turtles were saved. BBC.

- Bjorndal, K. A., Bolten, A. B. & Chaloupka, M. Y. (2005). Evaluating trends in abundance of immature green turtles, Chelonia mydas, in the greater Caribbean. Ecological Applications, 15, 304-314.

- Carr, A., Carr, M. H., & Meylan, A. B. (1978). The ecology and migrations of sea turtles, 7: The West Caribbean green turtle colony. Bulletin of American Museum of Natural History, 162(1), 1-46.

- Carr, A. & Ogren, L. (1960, November 30). The ecology and migrations of sea turtles, 4: The green turtle in the caribbean sea. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 121(1), 1-48.

- Craig, P., Parker, D., Brainard, R., Rice, M., & Balazs, G. (2004). Migrations of green turtles in the central South Pacific. Biological Conservation, 116, 433-438.

- Ernst, C. H. & Barbour, R. W. (1992, November 17). Turtles of the World. Washington, District of Columbia: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Fitzsimmons, N. N., Tucker, A. D., & Limpus, C. J. (1995). Long-term breeding histories of male green turtles and fidelity to a breeding ground. Marine Turtle Newsletter, 68, 2-4.

- Fleming, E. H. (2001, April). Swimming Against the Tide: Recent Surveys of Exploitation, Trade, and Management of Marine Turtles in the Northern Caribbean. Washington D.C.: TRAFFIC North America.

- Frazier, J. (1971, March). Observations on sea turtles at Aldabra Atoll. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. Biological Sciences, 260(836), 373-410.

- George, R. H. (1997, January). Health problems and diseases in sea turtles. In P. L. Lutz & J. A. Musick (Eds.), The Biology of Sea Turtles (pp. 363-409). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Gorga, C. C. T. (2010, August). Foraging ecology of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) on the Texas coast, as determined by stable isotope analysis. (Master’s thesis). Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

- Groombridge, B. & Luxmoore, R. (1989). The Green Turtle and Hawksbill (Reptilia: Cheloniidae): World Status, Exploitation and Trade. Lausanne, Switzerland: Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

- Guinea, M. (1993, August). South Pacific Regional Environment Programme: Sea turtles of Fiji. Northern Territory, Australia: Northern Territory University.

- Hersh, K. (2016). “Chelonia mydas“, Animal Diversity Web (ADW).

- Hirth, H. F. (1971). South Pacific Islands: Marine turtle resources. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Humphrey, S. L. & Salm, R. V. (Eds.). (1995, November 12). Status of Sea Turtle Conservation in the Western Indian Ocean: Proceedings of the Western Indian Ocean Training Workshop and Strategic Planning Session on Sea Turtles, held at Sodwana Bay, South Africa. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 165. IUCN/UNEP.

- Laguex, C. J. (1999, November 16). Status and distribution of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, in the wider Caribbean region: A dialogue for effective regional management. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: Wildlife Conservation Society.

- Lohmann, K. J. & Lohmann, C. M. F. (1996). Orientation and open-sea navigation in sea turtles. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 199(1), 73-81.

- Lohmann, K. J., Swartz, A. W., & Lohmann, C. M. F. (1995). Orientation and open-sea navigation in sea turtles. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 198(5), 1079-1085.

- Lutcavage, M. E., Plotkin, P., Witherington, B., & Lutz. P. L. (1997). Human impacts on sea turtle survival. In P. L. Lutz & J. A. Musick (Eds.), The Biology of Sea Turtles (pp. 107-136). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Marcovaldi, M. A., & dei Marcovaldi, G. G. (1999). Marine turtles of Brazil: The history and structure of Projeto TAMAR-IBAMA. Biological Conservation, 91(1), 35-41.

- Märzhäuser, H. (2018, February 16). Too hot for turtle guys: Great Barrier Reef is dangerously warm for male green sea turtles. Deutsche Welle.

- National Geographic Society. Green sea turtle. National Geographic.

- North Florida Ecological Services Office. (2017, February 16). Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas). United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Raj, U. (1977). Turtle farming for the South Pacific. South Pacific Bulletin, 3rd Quarter, 14-16.

- Rubio, M. (2009, September). Nesting beach characteristics of endangered sea turtles in Las Perlas Archipelago, Panama. (Master’s Dissertation). Edinburgh, Scotland: Heriot-Watt University.

- Russell, D. J., Hargrove, S., & Balazs, G. H. (2011, July). Marine sponges, other animal food, and nonfood items found in digestive tracts of the herbivorous marine turtle Chelonia mydas in Hawai’i. Pacific Science, 65(3), 375-381.

- Santoro, M. & Mattiucci, S. (2009, January). Sea turtle parasites. In I. S. Wehrtmann & J. Cortés (Eds.), Marine Biodiversity of Costa Rica, Central America (pp. 507-519). Berlin, Germany: Springer and Business Media B.V.

- Seminoff, J. A. (Southwest Fisheries Science Center, U.S.). (2004). Chelonia mydas. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2004: e.T4615A11037468.

- Seminoff, J. A., Resendiz, A., & Nichols, W. J. (2002, October). Home range of green turtles Chelonia mydas at a coastal foraging area in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 242, 253-265.

- Spotila, J. (2004, October 26). Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Spotila, J. 2004. Spotila, J. 2004. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. . Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Stokes, K. L., Broderick, A. C., Canbolat, A. F., Candan, O., Fuller, W. J., Glen, F., Levy, Y., Rees, A. F., Rilov, G., Snape, R. T., Stott, I., Tchernov, D., & Godley., B. J. (2015, June). Migratory corridors and foraging hotspots: Critical habitats identified for Mediterranean green turtles. Diversity and Distributions, 21(6), 665-674.

- Survival Service Commission. (1971, October). Marine turtles: Proceedings of the 2nd working meeting of marine turtle specialists. Morges, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

- Tacutu, R., Thornton, D., Johnson, E., Budovsky, A., Barardo, D., Craig, T., Diana, E., Lehmann, G., Toren, D., Wang, J., Fraifeld, V. E., & de Magalhaes, J. P. (2017, October 14). AnAge entry for Chelonia mydas In Human Ageing Genomic Resources (HAGR): new and updated databases.” Chelonia mydas 46(D1):D1027-D1033.

- Witherington, B. E. (1992). Behavioral responses of nesting sea turtles to artificial lighting. Herpetologica, 48(1), 31-39.

- Witherington, B. E. & Bjorndal, K. A. (1991, December). Influences of artificial lighting on the seaward orientation of hatchling loggerhead turtles, Caretta caretta. Biological Conservation, 55, 139-149.

- Witzel, W. N. (1982, February 23). Observations on the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Western Samoa. Copeia, 1982(1), 183-185.